The Perils Of Rare Events

A review of The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable

Why is is that we would be shocked to find someone 55 feet tall, but we routinely hear of people making $5.6 million a year or more and think nothing of it? The former represents an individual only 10 times the average height, while the latter has a salary 100 times the average household income in the US. As Nassim Taleb explains in The Black Swan, these two quantities comes from fundamentally different realms. The first is generated by the natural world, what Taleb refers to as Mediocristan, while the second is a product of the recent technological world created by humans, Extremistan.

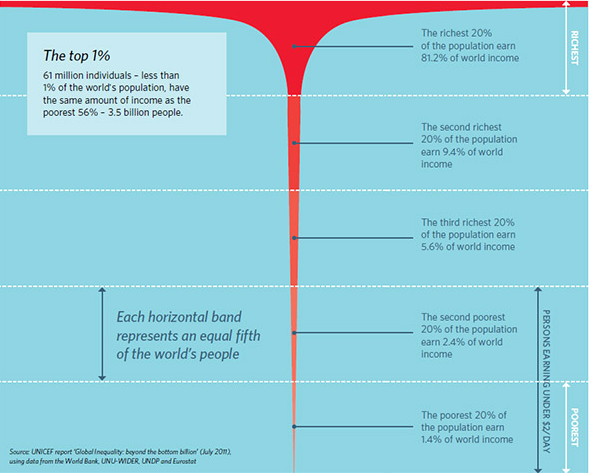

For nearly all of human history, we have occupied Mediocristan, where quantities are normally distributed with few values far from the average and no extreme values. Almost all phenomenon in nature behave in this manner: there are no animals that live for 10,000 years, no trees miles tall, and no humans that can run 100 miles per hour. It is only in the past century as a result of science and technological advances that we have constructed Extremistan, where outlying values such as Bill Gates’ net worth of $80 billion (about 300,000 times the average American net worth) or books sales of 500 million (the first Harry Potter) are entirely possible. These professions, computer software and creative fields, are examples of jobs that are infinitely scalable, that is, the amount of gain added does not scale linearly with the amount of effort put in. If J.K. Rowling writes a successful book that sells 10,000 copies, she does not have to put in 10 times as much effort to write a book that sells 100,000 copies. She can add another zero to the total sales with a minimal amount of effort. In contrast, traditional professions, such as baking scale linearly. In order for a baker to sell another loaf of bread, he has to bake another loaf and 10 times more sales means making 10 times as many loaves. As Taleb points out, if you want to become very wealthy, choose an infinitely scalable profession rather than a linearly scaling one where you are paid in direct proportion to the amount of hours worked.

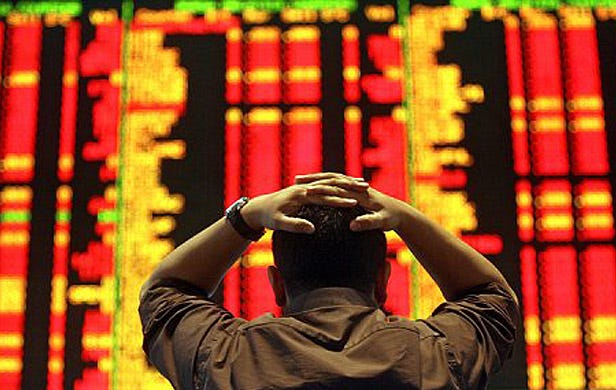

Evolution has not prepared us for quantities which can take on such a vast array of values. We are therefore ill-equipped to handle or even process events far out of the ordinary. The 777 point drop in the stock market on September 9, 2008 sent the entire world into a panic because we were used to seeing moves on the order of a few points up or down in a day. Finance, Taleb’s area of expertise, is one of the best examples of a field that lives in Extremistan. The wealth of individuals, the GDP of nations, and the value of stocks are all values that differ by numerous orders of magnitude, unlike most quantities in the natural world. There is simply no way to comprehend how three individuals (Gates, Warren Buffet, and Jeff Bezos) are worth more than the bottom 50% of Americans combined. The massive range of possible values for these quantities mean they can change by an unthinkable amount in a few hours, leaving us totally unprepared for the consequences. Finance is not the only modern pursuit to create extreme swings. Science and technology have created many values that are not normally distributed. Book sales, social media followers, search engine users, and battle deaths all tend to have a few outliers that vastly exceed the other examples combined. The World Wars were so terrible because the destruction dwarfed that of any previous conflict. We do not prepare for these events because they are simply out of our consideration, which served us well for 99% of human history, but now does not know how to handle numbers outside of “reasonable” ranges.

Global Wealth: Not a Normal Distribution (Source)

Global Wealth: Not a Normal Distribution (Source)

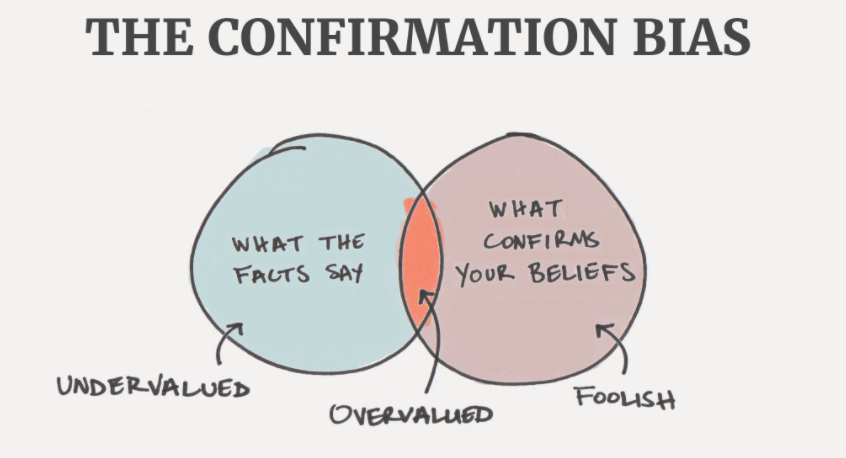

“Black Swan” refers to the theory that residents of Europe only believed that white swans existed until they encountered black swans in Australia. The Europeans, like most of us today, suffered from what is known as confirmation bias. Rather than seek out examples that would have disproved their white swan theory, such as a single black swan, they kept seeing only white swans which further entrenched their (false) belief. We do this often, especially in politics where we tend to follow only news sources that confirm our biases and ignore evidence that goes against our personal beliefs. However, in order to prepare for Black Swan events, we should look for disconfirmatory evidence, observations that disprove our theories. It only takes a single counterexample, like the stock market crash of 1929 to show our theory about the rationality of markets is incorrect. By seeking only confirmation, we blind ourselves to the possibility that our ideas may be wrong, often with disastrous results.

Confirmation Bias (Source)

Confirmation Bias (Source)

When a black swan does occur we try to rationalize it after the fact, a process known as hindsight bias. As humans, we like to believe the world obeys certain rules, and for the most part this served us well in our carefree days in Mediocristan. However, by justifying past events with a well-told narrative, we downplay the chance of future extreme events and therefore do not take them into consideration when planning our daily lives. While it would be foolish to take this idea too far and live constantly in fear of an event we cannot see coming we should be more open to the concept that rare phenomenon actually occur all the time, particularly in the recent fields of finance, science, and technology.

What to Do?

How can we deal with events that we don’t see coming and are outside of our realm of experience? Well, first we should give up trying to predict black swans because, as Taleb states, while we think that intelligent individuals make accurate predictions, it is in fact the smartest people who admit their uncertainty about the future. Instead of making uncertain forecasts, we can build up our robustness. For banks, that might mean maintaining more low-risk bonds than high risk stocks on the chance that the market takes a turn for the worse. On a personal level, we should try to learn from our small failures in order to avoid potentially larger ones down the road. We can learn the perils of playing the daily stock market from investing a few hundred dollars in penny stocks and avoid the larger mistake of losing all of our retirement savings. Taleb has outlined 10 principles to build resilience against Black Swans which includes holding individuals and institutions responsible for past mistakes, and making systems as simple as possible so they can be easily monitored for problems. It is imprudent to attempt to predict specific Black Swans, but if we prepare for the possibility of any Black Swan, then we will be better equipped to deal with the consequences.

Recommendation

As always, I judge a book by whether or not I can get the whole picture from a five-minute summary or if I need to read the entire book. In the case of the Black Swan, I would not recommend reading all of the book. Taleb covers a lot of interesting concepts, such as human biases, but they are not topics unique to his writing. He does provide a few personal anecdotes which help to reinforce the ideas but he also constructs several fake narratives to illustrate his points which I found distracting. If you want to learn about biases, I recommend Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahnemann (or any of his research papers written with Amos Tversky). There are a number of good web pages on the general Black Swan theory and the basic idea can be wrapped up in one sentence: rare events happen more than we think they will, and while we cannot predict them precisely in advance, we can construct our society to be more resilient to surprises. It’s a valuable concept, and if we want to enjoy the benefits of science, technology, and finance, then we must reckon with their unique tradeoffs for which our natural history has not prepared us.

Have any book recommendations for me or want to chat about data science, programming, or ultramarathon running? I can be reached on twitter at @koehrsen_will.