Is The Job Of Data Scientist At Risk Of Being Automated

A useful test for determining if your job can be done by a machine with an application to data scientist

Amara’s Law states we tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short term but underestimate the effect in the long term. We see this play out repeatedly with technologies ranging from trains to the internet to now machine learning. The trend is nearly always the same: initial, wildly optimistic claims about the capabilities of an innovation are followed by a period of disillusionment when it fails to deliver before finally, we figure out how to use the technology and it goes on to fundamentally reshape our entire world (this is known as the hype cycle).

The basic idea of Amara’s Law — smaller short-term effects than claimed but much larger long-term effects than was imagined — can also be seen repeatedly in the overall effect of technology on the job humans do. The first steel plow, invented in the 1830s, did not immediately displace all farmers, but over the period from 1850 to modern times, the percentage of people working agriculture jobs in the US went from >50% to <2%. (Through a combination of innovations, not just mechanical technology, a far smaller percentage of people now produce a vastly larger amount of food.)

Likewise, US manufacturing jobs went from 40% of the total jobs to less than 10%, not in one or two years, but over decades (through a combination of automation and outsourcing). Again we see minor ripples over the course of a few years, but a fundamental restructuring of the economy over a long enough time period. Moreover, it’s critical to point out that people always find other jobs. Today, we have the lowest unemployment levels in 50 years, because when some jobs are automated, humans simply switch to new jobs. We constantly invent new careers to meet our needs, including the entire service economy (which employs the majority of Americans since the decline of agriculture and manufacturing), or, on a personal level, the role of data scientist, which became widely recognized only in 2012.

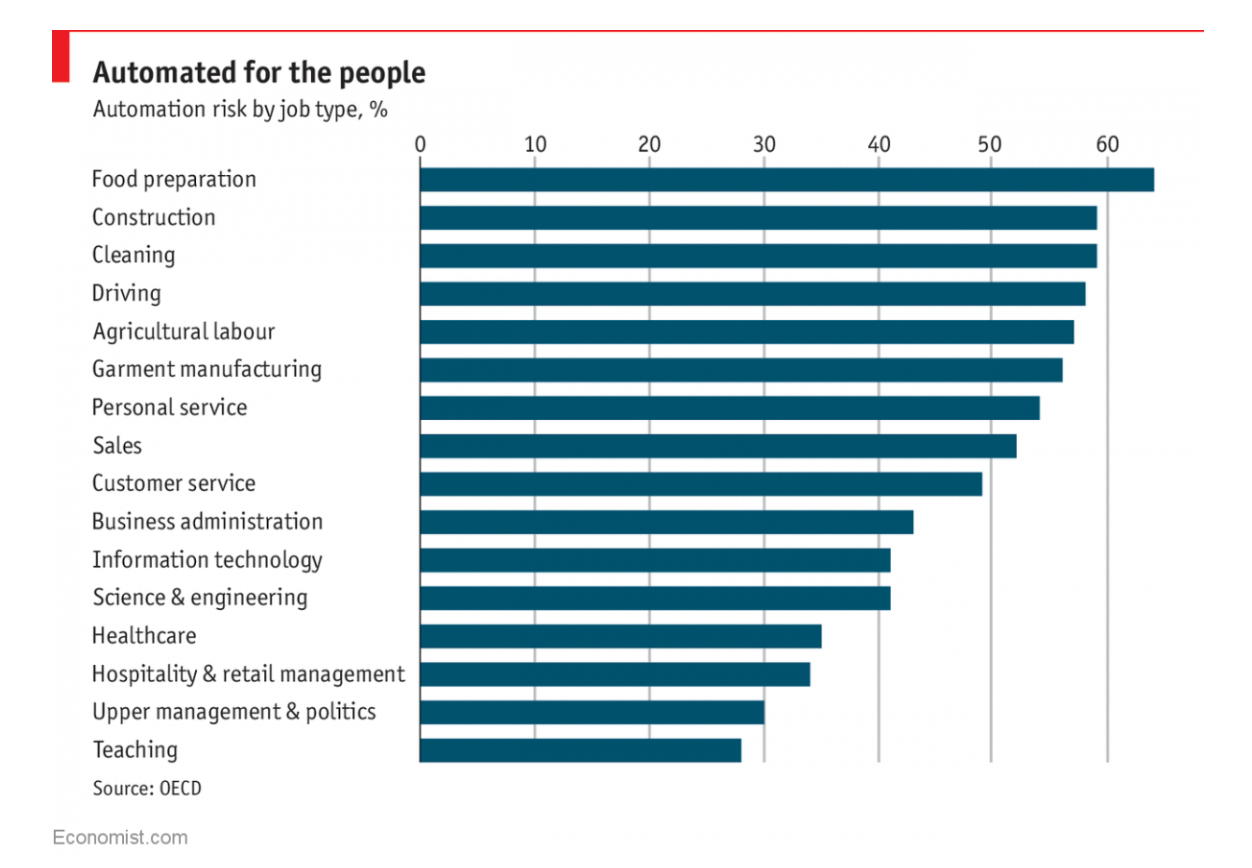

It’s worth keeping these two points — change takes time and we’ll always invent new jobs for humans— in mind when we think about the effects of automation in current times. It can be easy to get carried away with reports claiming “Nearly Half of Jobs Are Vulnerable to Automation” which seem to imply we should be concerned about masses of unemployed workers within a few years.

Nothing gets more clicks than fear! (Source)

Nothing gets more clicks than fear! (Source)

Thinking in terms of Amara’s Law, I would argue this study is underestimating the percentage of jobs which will be done by machines: 99% of our jobs will be rendered obsolete because of new technology, but only over a long enough time scale. As our jobs are gradually automated, we’ll simply move along to the next, likely a career that has not yet been invented.

In the short term, effects of technology are overstated, but in the long term understated, including the effects of technology on the job market.

With that being said, it’s still interesting to think about which jobs are likely to be automated in the short term and why, so we can focus on learning the skills where humans add the most value. In his excellent book The Fourth Age: Smart Robots, Conscious Computers, and the Future of Humanity, Byron Reese lays out the characteristics of jobs at high risk for automation. These are:

- Repetitive: either physically or mentally

- Low creativity: no need for improvisation and novel ways of thinking

- Low social IQ: no communication, persuasion, or charisma required

- Limited training: the ease of automating a job is inversely proportional to the length of a “manual” it would take to fully describe that job

In addition to describing these traits in detail, Reese outlines a handy tool for determining the “automation risk” of your job. The following 10 questions are no guarantee a job will be or will not be automated, but they do provide a framework for quantifying what to most people is usually an emotional question: “will robots take my job?” (the answer is that most people think machines won’t take their job, but will take other people’s jobs.

The Test

I’ll go through the questions and answer them based on what I’ve learned as a data scientist. This is not meant to be an objective analysis of the entire field — every position is different, so feel free to disagree. For background, I’ve spent 2 years in the data science field: 1 year on a graduate research project, 2 months as a data analyst intern at Pratt and Whitney, 4 months as a data scientist at Feature Labs, and 6 months as a full-time data scientist at Cortex Building Intelligence. I’m primarily answering these questions with respect to my current job at Cortex, where we use big data and machine learning to increase energy efficiency of commercial office buildings (proving you can make a positive environmental and economic impact at the same time). We are a small startup (~10 people) and I neither manage any employees nor have a formal manager although I work closely with a senior software engineer.

This test is scored out of 100 with a higher score indicating greater vulnerability to automation. (The test appears in Chapter 10 of the book but I’d encourage you to read the entire book. You can also take the test online for yourself; I’ve rephrased some of the questions for clarity).

- How similar are two days at your job? (0: not at all, 10: very similar)

4 / 10. While writing code can occasionally feel formulaic, a job as a data scientist involves more than building machine learning models. Some days I may spend refactoring code (something I’ll be glad to hand over to machines), some days I’ll run a one-off data analysis for a client, and other days I’ll have to go to a building to adjust some faulty sensors to get reliable data. (Oh, you thought all data comes neatly packaged and hand-delivered in a clean csv file? Well, welcome to the real world, where getting data means crawling around the basement of an office building to reconnect an electric meter). In short, the day-to-day similarity is low which makes the job exciting and less susceptible to a machine takeover.

2. How often do you have to move physical locations at your job? (0: never, 10: at all times)

6 / 10. For most data scientists/software engineers, I’m guessing this answer is higher on the scale because you work in the same office at the same desk every day. For my role, I do spend a lot of time at one desk, but I also go to different buildings around New York City. (Again, you can’t do data science without data and getting that data requires significant effort.) Moreover, I split time between our offices in NYC and HQ in Washington, DC, because, at the end of the day, face-to-face conversations are most effective.

3. How many people know of or do your job? (0: almost none, 10: many)

5 / 10. When you are in a field, it can be easy to get caught in a filter bubble where you think your job is Very Important and therefore everyone must know about it. Even a few short conversations with people outside the field will dispel you of this notion, as I have found with data science. Few people outside of the tech space have heard the term “data scientist” let alone know what one does. I’ve resorted to saying I analyze data, and if that doesn’t get across to people, I’ll mention something about computers and spreadsheets. In general, the more specialized the job (meaning fewer workers are doing it), the less likely it is to be automated because there is less incentive to invest the resources needed to build a machine capable of the job.

4. How long is the training for your job? (0: years, 10: days)

0 / 10. Training for data science is extensive — you cannot learn all there is to know in a 6 or even 12-week bootcamp. Although I don’t believe a 4-year degree is necessary to be successful, you will need to study for a prolonged time and gain experience solving actual problems before you can be an effective data scientist in industry. Furthermore, the job requires constant learning, always being on the lookout for new tools and better methods to solve your problems. Any machine taught data science would need a “mental upgrade” about every 6 months to stay current.

5. Does your job require repetitive physical actions? (0: not at all, 10: completely)

8 / 10. My answer is again probably lower than most other data scientists since I have to help integrate our technology at buildings. This is one area where we don’t stand a chance next to machines; computers are absolutely great at repeatedly doing the same thing millions of times with no mistakes. If we could just tell the computers the correct keys to type, we’d immediately be out of a job.

6. What is the longest time you need to make a decision? (0: more than 5 minutes, 10: few seconds)

0 / 10 Reese (the author of the test) sets the maximum time for this question at 5 minutes which seems awfully short. There are decisions we make at Cortex that take weeks of poring over results and deliberation among employees at all levels of the company. Almost our decisions involve not only quantitative metrics (numbers) but qualitative measures (can we explain this to our clients, are the features human-understandable). The data science solutions we build are not determined solely by the one with the lowest error, but through reasoned decision taking into account many different needs.

7. Does your job require an emotional connection to other people? (0: absolutely necessary, 10: not at all necessary)

5 / 10. If you thought you could escape people by becoming a data scientist, then sorry, you’ve chosen the wrong profession. Working successfully at a company requires constant communication: in a typical day, I may talk to clients, the CEO, the sales team, and the customer success team, all of whom respond best to different approaches (quantitative vs qualitative, assertive vs open-ended). That is not even considering my conversations with other engineers which involve code reviews, looking at model outputs, developing new solutions to problems, debating code style, etc. In short, hone up on your communication skills if you plan to work at any company.

8. Is creativity required at your job? (0: entire basis of job, 10: creativity actively discouraged)

4 / 10. Perhaps I amoverstating how much creativity I perceive goes into data science, but we constantly face new problems that can’t be solved with the same approaches, which means we need to “think differently”. If we consider creativity to include the ability to use many different tools, then data science has to rank high on the scale. I wish there were established best practices for solving problems in data science, but for better or worse, that is not the case. Therefore my job requires trying out numerous approaches to every problem and sometimes developing my own if no existing ones will do.

9. Do you directly manage employees? (0: many, 10: none)

10 / 10. As an individual contributor, I do not directly manage any employees. Nonetheless, managing is certainly not out of the question for a data scientist.

10. Would someone else do your job in the same way? (0: not at all, 10: exactly the same)

4 / 10. At this point in the evolution of data science, the answer is a solid no. There are too many ways to solve data science problems for two people to use the same method. I’ve had occasions to re-implement modeling pipelines that were built several years ago, and each time I’ve been struck by how much easier the code is to write now with up-to-date tools. In addition to the tools, fundamental approaches can differ: use a simple model with extensive feature engineering, or limit the features and use a complex model. Eventually, the data science field may collapse on a few approaches, but even at that point, there will still be plenty of room for individual nuance when doing the job.

Total Vulnerability of Data Science to Automation: 46 / 100

According to Reese, any job below 70 is safe for an entire career. Although I think data science is at no risk of being automated (be skeptical of companies trying to sell you automated data science tools )in the short term, I’m not confident the role of “data scientist” will still exist a decade from now.

Instead, I think data science tools will continue to get easier to use until non-specialists can employ them effectively. At that point, data science will be an essential skill, but one not limited to a handful of experts and we won’t need anyone trained specifically in data science. I’m hopeful for this time, because I’ve repeatedly seen the importance of domain expertise for building effective data science pipelines. If we can put the right tools in the hands of those with experience in a field, then data science can deliver on its promises of increasing efficiency and enabling objective decisions. In summary, automation is not likely to take data science jobs, but if the right tools are developed, data scientist may become an extraneous specialization.

If Not Automation, then What Should We Worry About?

There are more realistic problems facing data science than the immediate specter of robots taking our jobs. This is worth a more in-depth investigation, but for now, start thinking about how we can solve these issues:

- Overpromising and under-delivering: there is a wide gap between what data science can actually do and what is portrayed in the media. Data science is not a miracle cure to be thrown at every problem and deploying machine learning models in production (something we do at Cortex hundreds of times a day) requires an extremely uncommon blend of the right data and the expertise to make use of it. The truth is most value for companies is in just visualizing data currently hidden in spreadsheets (or automating simple spreadsheet tasks with a little Python). Most companies do not have the capabilities or the need for deep learning. Avoid the hype train or risk losing trust when you can’t deliver.

- Algorithmic Bias: Anyone training to be a data scientist should be required to read Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O’Neill. To summarize an extraordinary read, algorithms reinforce and amplify existing biases when they are trained on biased data. The humans developing the models do not even have to be prejudiced themselves for existing inequalities to be perpetuated under the auspices of machine learning. Data science promises to be objective, but there is nothing objective about data collection or analysis. If we want data science to benefit the most people possible, then we need to start thinking about how to get the bias out of our models which includes welcoming and supporting a more diverse group of contributors.

- Results that can’t be reproduced. It’s easy to do a one-off analysis and present a finding in an academic paper, but a much harder task to get results which can be reproduced repeatedly even on the same data on the same machine! This problem is finally starting to get some attention and I’m hopeful the broader issue of reproducibility in science can lead to new tools or approaches. A lack of reproducible results leads to a deterioration of trust in data science methods: if you tell your clients one number one day and a completely different number for the same outcome at a later time, why would they rely on your predictions?

- Crumbling data science infrastructure: More people than ever before are using open-source data science tools (think Python, numpy, scikit-learn, pandas, matplotlib, scipy, pymc3) but the contributor and maintainer base is not growing accordingly. Free and Open Source Software is great, but it’s hard for contributors to maintain the tools when they are doing it voluntarily on top of a full-time job (see this report for a great rundown of the problem). There are many ways to contribute, from submitting bugs to fixing issues to simply donating money (go here right now and become a recurring donor to NumFocus if you want to help), and we need to start supporting the very foundations upon which our field stands. This is a critical issue that unfortunately does not receive much attention and I’ve written previously on this topic because it’s crucial.

In addition to the above, I’m also concerned that formal education systems are not producing effective data scientists. With students trained specifically in data science, there may be many data scientists who can write a superb Jupyter Notebook, but have no idea how to put a machine learning model into production. There is an immense gap between getting a result once on a clean dataset in a Jupyter Notebook and running a model hundreds of times every day on real data with results served to clients. I don’t know if this gap can be bridged in a university setting by the current curriculums.

As a final note, at Cortex, we have never been limited in what features we could build by data science — the techniques themselves are simple to implement with open-source tools — but rather by the intricacies required to get data, clean the data, format it currently, run the models and deliver those predictions (with explanations) to customers. My advice would be to spend some serious time learning software engineering and data engineering alongside traditional data science statistics and programming courses.

Although the role of “data scientist” might not last that long — not because of automation but because of easier-to-use tools — the skills learned in data science are only becoming more relevant. For better or worse, we live in a data-saturated, technology-driven world, and the capability to make sense of data and manipulate technology to do your bidding (instead of the other way round) is critical. If you are a current data scientist, keep applying those skills and learning new ones. For those studying to get into the field, recognize you are preparing not necessarily for the position of “data scientist”, but rather for a world in which the skills of data science will become increasingly valued.

I write articles on data science and occasionally other interesting topics. You can reach me on Twitter @koehrsen_will. If helping the environment and the bottom line appeals to you, then maybe reach out to us at Cortex.