Data Scientists Your Variable Names Are Awful Heres How To Fix Them

Wading your way through data science code is like hacking through a jungle. (Source)

Wading your way through data science code is like hacking through a jungle. (Source)

A Simple Way to Greatly Improve Code Quality

Quick, what does the following code do?

for i in range(n):

for j in range(m):

for k in range(l):

temp_value = X[i][j][k] * 12.5

new_array[i][j][k] = temp_value + 150

It’s impossible to tell right? If you were trying to modify or debug this code, you’d be at a loss unless you could read the author’s mind. Even if you were the author, a few days after writing this code you wouldn’t know what it does because of the unhelpful variable names and use of “magic” numbers.

Working with data science code, I often see examples like above (or worse): code with variable names such as X, y, xs, x1, x2, tp, tn, clf, reg, xi, yi, iiand numerous unnamed constant values. To put it frankly, data scientists (myself included) are terrible at naming variables when we go to the trouble of naming them at all.

As I’ve grown from writing research-oriented data science code for one-off analyses to production-level code (at Cortex Building Intel), I’ve had to improve my programming by unlearning practices from data science books, courses, and the lab. There are many differences between machine learning code that can be deployed and how data scientists are taught to program, but we’ll start here by focusing on two common problems with a large impact:

- Unhelpful/confusing/vague variable names

- Unnamed “magic” constant numbers

Both these problems contribute to the disconnect between data science research (or Kaggle projects) and production machine learning systems. Yes, you can get away with them in a Jupyter Notebook that runs once, but when you have mission-critical machine-learning pipelines running hundreds of times per day with no errors, you have to write readable and understandable code. Fortunately, there are best practices from software engineering we data scientists can adopt to this end, including the ones we’ll cover in this article.

Note: I’m focusing on Python since it’s by far the most widely used language in industry data science. In Python (see here for more details):

- Variable/function names are

lower_caseandseparated_with_underscores - Named constants are in

ALL_CAPITAL_LETTERS - Classes are in

CamelCase

Naming Variables

There are three fundamental ideas to keep in mind when naming variables:

- The variable name must describe the information represented by the variable. A variable name should tell you specifically in words what the variable stands for.

- Your code will be read more times than it is written. Prioritize how easy your code is to understand rather than how quickly it is written.

- Adopt standard conventions for naming so you can make one global decision instead of multiple local decisions.

What does this look like in practice? Let’s go through some improvements to variable names:

Xandy. If you’ve seen these several hundred times, you know they are features and targets, but that may not be obvious to other developers reading your code. Instead, use names that describe what these variables represent such ashouse_featuresandhouse_prices.value. What does the value represent? It could be avelocity_mph,customers_served,efficiency,revenue_total. A name likevaluetells you nothing about the purpose of the variable and is easily confused.temp. Even if you are only using a variable as a temporary value store, still give it a meaningful name. Perhaps it is a value where you need to convert the units, so in that case, make it explicit:

# Don't do this

temp = get_house_price_in_usd(house_sqft, house_room_count)

final_value = temp * usd_to_aud_conversion_rate

# Do this instead

house_price_in_usd = get_house_price_in_usd(house_sqft,

house_room_count)

house_price_in_aud = house_price_in_usd * usd_to_aud_conversion_rate

- If you are using abbreviations like

usd, aud, mph, kwh, sqftmake sure you establish these ahead of time. Agree with the rest of your team on common abbreviations and write them down. Then, in code review, make sure to enforce these written standards. tp,tn,fp,fn: Avoid machine learning specific abbreviations. These values representtrue_positives,true_negatives,false_positives, andfalse_negatives, so make it explicit. Besides being hard to understand, the shorter variable names can be mistyped. It’s too easy to usetpwhen you meanttn, so write out the whole description.- The above is an example of prioritizing ease of reading code instead of how quickly you can write it. Reading, understanding, testing, modifying, and debugging poorly written code takes far longer than well-written code. Overall, by trying to write code faster — using shorter variable names — you will actually increase the development time of your program! If you don’t believe me, go back to some code you wrote 6 months ago, and try to modify it. If you find yourself trying to decipher your code, that’s an indication you should be concentrating on better naming conventions.

xsandys. These are often used for plotting, in which case the values representx_coordinatesandy_coordinates. However, I’ve seen these names used for many other tasks, so avoid the confusion by using specific names that describe the purpose of the variables such astimesanddistancesortemperaturesandenergy_in_kwh.

What Causes Bad Variable Names?

Most problems with naming variables stem from

- A desire to keep variable names short

- A direct translation of formulas into code

On the first point, while languages like Fortran did limit the length of variable names (to 6 characters), modern programming languages have no restrictions so don’t feel forced to use contrived abbreviations. Don’t use overly long variable names either, but if you have to favor one side, aim for readability.

With regards to the second point, when you write an equation or use a model — and this is a point schools forget to emphasize — remember the letters or inputs represent real-world values!

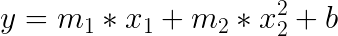

Let’s see an example that makes both mistakes and how to correct it. Say we have a polynomial equation for finding the price of a house from a model. You may be tempted to write the mathematical formula directly in code:

```

```

temp = m1 * x1 + m2 * (x2 ** 2) final = temp + b

This is code that looks like it was written by a machine for a machine. While a computer will ultimately run your code, it will be read far more times by humans, so write code that is meant for human understanding!

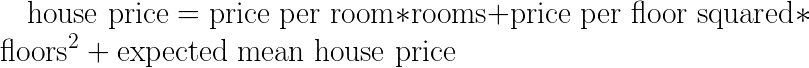

To do this, we need to think not about the formula itself — the _how_ — and consider the real-world objects being modeled — the _what_. Let’s write out the complete equation (this is a good test to see if you understand the model):

*```*

house_price = price_per_room * rooms + \

price_per_floor_squared * (floors ** 2)

house_price = house_price + expected_mean_house_price

If you are having trouble naming your variables, it means you don’t know the model or your code well enough. We write code to solve real-world problems, and we need to understand what our model is trying to capture. Descriptive variable names let you work at a higher level of abstraction than a formula, helping you focus on the problem domain.

Other Considerations

One of our important points to remember for naming variables was consistency counts. Being consistent with variable names means you spend less time worrying about naming, and more time solving the problem. This point is relevant when you add aggregations to variable names.

Aggregations in Variable Names

So you’ve mastered the basic idea of using descriptive names, changing xs to distances, e to efficiency, and v to velocity. Now, what happens when you take the average of velocity? Should this be average_velocity, velocity_mean or velocity_average? Two steps can resolve this:

- First, decide on common abbreviations:

avgfor average,maxfor maximum,stdfor standard deviation and so on. Make sure all team members agree and write these down. - Put the abbreviation at the end of the name. This puts the most relevant information, the entity described by the variable, at the beginning.

Following these rules, your set of aggregated variables might be velocity_avg , distance_avg, velocity_min, and distance_max. Rule 2. is kind of a personal choice, and if you disagree, that’s fine, as long as you consistently apply whatever rule you choose.

A tricky point comes up when you have a variable representing the number of an item. You might be tempted to use building_num, but does that refer to the total number of buildings, or the specific index of a particular building? To avoid ambiguity, use building_count to refer to the total number of buildings and building_index to refer to a specific building. You can adapt this to other problems such as item_count and item_index . If you don’t like count , then item_total also is a better choice than num.This approach resolves ambiguity and maintains the consistency of placing aggregations at the end of names.

Loop Indexes

For some unfortunate reason, typical loop variables have become i, j, and k. This may be the cause of more errors and frustration than any other practice in data science. Combine uninformative variable names with nested loops (I’ve seen loops nested to include the use of ii, jj, and even iii) and you have the perfect recipe for unreadable, error-prone code. This may be controversial, but I never use i or any other single letter for loop variables, opting instead for describing what I’m iterating over such as

for building_index in range(building_count):

....

or

for row_index in range(row_count):

for column_index in range(column_count):

....

This is especially useful when you have nested loops so you don’t have to remember if i stands for row or column or if that was j or k. You want to spend your mental resources figuring out how to create the best model, not trying to figure out the specific order of array indexes.

(In Python, if you aren’t using a loop variable, then use _ as a placeholder. This way, you won’t get confused about whether or not the index is used.)

More Names to Avoid

- Avoid using numerals in variable names

- Avoid commonly misspelled words in English

- Avoid names with ambiguous characters

- Avoid names with similar meanings

- Avoid abbreviations in names

- Avoid names that sound similar

All of these stick to the principle of prioritizing read-time understandability instead of write-time convenience. Coding is primarily a method for communicating with other programmers, so give your team members some help in making sense of your computer programs.

Never Use Magic Numbers

A magic number is a constant value without a variable name. I see these used for tasks like converting units, changing time intervals or adding an offset:

final_value = unconverted_value * 1.61

final_quantity = quantity / 60

value_with_offset = value + 150

(These variable names are all poor!)

Magic numbers are a large source of errors and confusion because:

- Only one person, the author, knows what they represent

- Changing the value requires looking up all the locations it is used and manually typing in the new value

Instead of using magic numbers, we can define a function for conversions that accepts the unconverted value and the conversion rate as parameters:

def convert_usd_to_aud(price_in_usd,

aud_to_usd_conversion_rate):

price_in_aus = price_in_usd * usd_to_aud_conversion_rate

If we use the conversion rate throughout a program in many functions, we could define a named constant in a single location:

USD_TO_AUD_CONVERSION_RATE = 1.61

price_in_aud = price_in_usd * USD_TO_AUD_CONVERSION_RATE

(Before we start the project, we should establish with the rest of our team that usd = US dollars and aud = Australian dollars. Remember standards!)

Here’s another example:

# Conversion function approach

def get_revolution_count(minutes_elapsed,

revolutions_per_minute):

revolution_count = minutes_elapsed * revolutions_per_minute

# Named constant approach

REVOLUTIONS_PER_MINUTE = 60

revolution_count = minutes_elapsed * REVOLUTIONS_PER_MINUTE

Using a NAMED_CONSTANT defined in a single place makes changing the value easier and more consistent. If the conversion rate changes, you don’t need to hunt through your entire codebase to change all the occurrences, because it is defined in only one location. It also tells anyone reading your code exactly what the constant represents. A function parameter is also an acceptable solution if the name describes what the parameter represents.

As a real-world example of the perils of magic numbers, in college, I worked on a research project with building energy data that initially came in 15-minute intervals. No one gave much thought to the possibility this could change, and we wrote hundreds of functions with the magic number 15 (or 96 for the number of daily observations). This worked fine until we started getting data in 5 and 1-minute intervals. We spent weeks changing all our functions to accept a parameter for the interval, but even so, we were still fighting errors caused by the use of magic numbers for months.

Real-world data has a habit of changing on you — conversion rates between currencies fluctuate every minute — and hard-coding in specific values means you’ll have to spend significant time re-writing your code and fixing errors. There is no place for “magic” in programming, even in data science.

Importance of Standards and Conventions

The benefits of adopting standards are that they let you make a single global decision instead of many local ones. Instead of choosing where to put the aggregation every time you name a variable, make one decision at the start of the project, and apply it consistently throughout. The objective is to spend less time on concerns only peripherally related to data science: naming, formatting, style — and more time solving important problems (like using machine learning to address climate change).

If you are used to working by yourself, it might be hard to see the benefits of adopting standards. However, even when working by yourself, you can practice defining your own conventions and using them consistently. You’ll still get the benefits of fewer small decisions and it’s good practice for when you inevitably have to develop on a team. Anytime you have more than one programmer on a project, standards become a must!

You might disagree with some of the choices I’ve made in this article, and that’s fine! It’s more important to adopt a consistent set of standards than the exact choice of how many spaces to use or the maximum length of a variable name. The key point is to stop spending so much time on accidental difficulties and instead concentrate on the essential difficulties. (David Brooks has an excellent essay on how we’ve gone from addressing accidental problems in software engineering to concentrating on essential problems).

Conclusions

Keeping what we’ve learned in mind, we can now go back to the initial code we started with:

for i in range(n):

for j in range(m):

for k in range(l):

temp_value = X[i][j][k] * 12.5

new_array[i][j][k] = temp_value + 150

and fix it up. We’ll use descriptive variable names and named constants.

Now we can see that this code is normalizing the pixel values in an array and adding a constant offset to create a new array (ignore the inefficiency of the implementation!). When we give this code to our colleagues, they will be able to understand and modify it. Moreover, when we come back to the code to test it and fix our errors, we’ll know precisely what we were doing.

Is this topic boring? Perhaps it’s a little dry, but if you spend time reading about software engineering, you realize what differentiates the best programmers is the repeated practice of such mundane techniques as good variable names, keeping routines short, testing every line of code, refactoring, etc. These are the techniques you need to move your code from research to production-level and, once you get there, you’ll see that having your models influencing real-life decisions is far from boring.

In this article, we covered some of the ways to improve your variable names.

Overall points to remember

- A variable name should describe the entity the variable represents.

- Prioritize how easy your code is to understand over how quickly you can write the code.

- Use consistent standards throughout a project to minimize the cognitive burden of small decisions.

Specific points

- Use descriptive variable names

- Use function parameters or named constants instead of “magic” numbers

- Don’t use machine-learning specific abbreviations

- Describe what an equation or model represents with variable names

- Put aggregations at the end of variable names

- Use

item_countinstead ofnum - Use descriptive loop indexes instead of

i,j,k. - Adopt conventions for naming and formatting across a project

(If you disagree with some of my specific advice, that’s fine. It’s more important that you are using a standard way to name variables than being dogmatic about the exact conventions!)

There are many other changes we can make to our data science code to get it to production level (we didn’t even talk about function names!). I’ll have more articles on this topic soon, but in the meantime, check out “Notes on Software Construction from Code Complete”. To dive in deep on software engineering best practices, pick up Code Complete by Steve McConnell.

To reach its true potential, data science will need to use standards that allow us to build robust software products. Fortunately for us, software engineers have already thought most of these best practices out and detailed them in countless books and articles. It’s now up to us to read and implement them.

I write about data science and welcome constructive comments or feedback. I can be reached on Twitter @koehrsen_will. If helping the world while boosting the bottom line appeals to you, then check out the openings at Cortex Building Intelligence. We help some of the largest office buildings in the world save hundreds of thousands of dollars on energy costs while reducing their carbon footprint.