The Copernican Principle And How To Use Statistics To Figure Out How Long Anything Will Last

(Source)

(Source)

Statistics, the lifetime equation, and when data science will end

The pursuit of astronomy has been a gradual process of uncovering the insignificance of humanity. We started out in the center of the universe with the cosmos literally revolving around us. Then we were rudely relegated to one of 8 planets orbiting the sun, a sun which subsequently was revealed to be just one of billions of stars (and not even a large one) in our galaxy.

This galaxy, the majestic Milky Way, seemed pretty impressive until Hubble discovered that all those fuzzy objects in the sky are billions of other galaxies, each of which has billions of stars (potentially with their own intelligent life). The demotion has only continued in the 21st century, as mathematicians and physicists have concluded the universe is one of an infinity of universes collectively called the multiverse.

Go here to be blown away

Go here to be blown away

On top of the relegation to a smaller and smaller part of the cosmos, now some thinkers are claiming we live in a simulation, and soon will create our own simulated worlds. All of this is a long way to say we are not special. The idea that the Earth, and by extension humanity, does not occupy a privileged place in the universe is known as the Copernican Principle.

While the Copernican Principle was first used with respect to our physical location — x, y, and z coordinates — in 1993, J Richard Gott applied the concept that we aren’t special observers to our universe’s fourth dimension, time. In “Implications of the Copernican principle for our future prospects” ($200 here or free through the questionably legal SciHub here), Gott explained that if we assume we don’t occupy a unique moment in history, we can use a basic equation to predict the lifetime of any phenomenon.

The Copernican Lifetime Equation

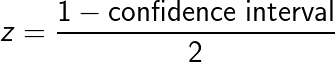

The equation, in its simple brilliance (derivation at the end of article) is:

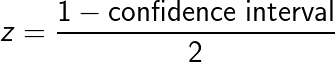

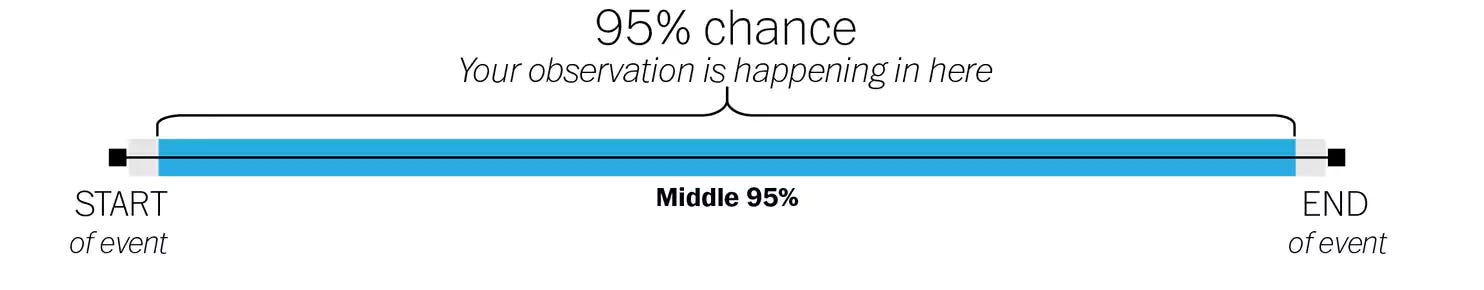

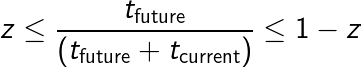

Where t_current is the amount of time something has already been around, t_future is the expected amount of time it will last from now, and confidence interval expresses how certain we are in the estimate. This equation is based on a simple idea: we don’t exist at a unique moment in time and therefore, when we observe an event, we are most likely watching the middle and not the beginning or the conclusion.

Where t_current is the amount of time something has already been around, t_future is the expected amount of time it will last from now, and confidence interval expresses how certain we are in the estimate. This equation is based on a simple idea: we don’t exist at a unique moment in time and therefore, when we observe an event, we are most likely watching the middle and not the beginning or the conclusion.

You are most likely not at the beginning or end of an event but in the middle (Source).

You are most likely not at the beginning or end of an event but in the middle (Source).

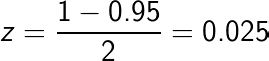

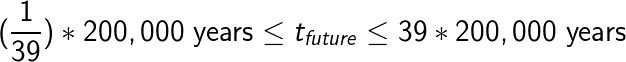

As with any equation, the best way to figure out how it works is to input some numbers. Let’s apply this to something simple, say the lifetime of the human species. We’ll use a 95% confidence interval and assume modern humans have been around for 200,000 years. Plugging in the numbers, we get:

The answer to the classic dinner-party question (okay, only the dinner parties I go to) of how long humans will be around is 5130 to 7.8 million years with 95% confidence. This is in close agreement with actual evidence that shows the mean duration of a mammal species is about 2 million years with the Neanderthals making it 300,000 years and Homo erectus 1.6 million years.

The neat part about this equation is it can be applied to anything while relying only on statistics instead of trying to untangle a complex underlying web of causes. How long a television show runs for, the lifetime of a technology, or the length of time a company exists are all subject to numerous factors that are impossible to tease apart. Rather than digging through all the causes, we can take advantage of the temporal (a fancy word for time) Copernican Principle and arrive at a decent estimate for the lifetime of any phenomenon.

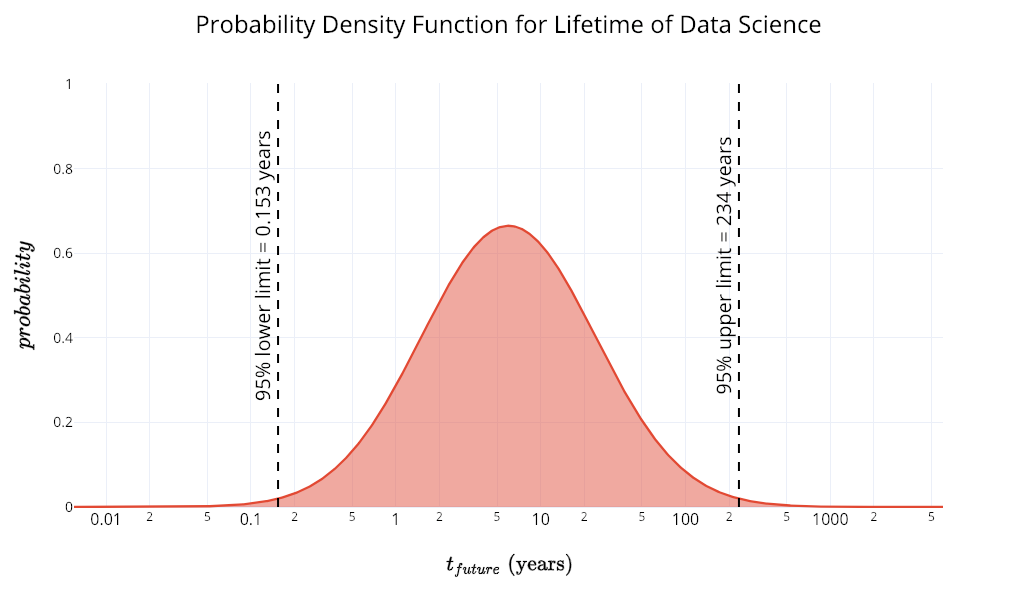

To apply the equation to something closer to home, data science, we first need to find the current lifetime of the field, which we’ll put at 6 years based on when the Harvard Business Review released the article “Data Scientist: The Sexiest Job of the 21st Century”. Then, we use the equation to find we can expect, with 95% confidence, data science will be around for at least another 8 weeks, and at most, 234 years.

If we want a narrower estimate, we reduce our confidence interval: at 50%, we get from 2 to 18 years.

This illustrates an important point in statistics: if we want to increase the precision, we have to sacrifice accuracy. A smaller confidence interval is less likely to be correct, but it gives us a narrower range for our answer.

If you want to play around with the numbers, here’s a Jupyter Notebook.

Being Right, Atomic Bombs, and Takeaways

You might object the answers from this equation are ridiculously wide, a point I’ll concede. However, the objective is not to get a single number — there are almost no situations, even when using the best algorithm, that we can find the one number guaranteed to be spot on — but to find a plausible range.

I like to think of the Copernican Lifetime Equation as a Fermi estimate, a back of the envelope style calculation named for the physicist Enrico Fermi. In 1945, with nothing more than some scraps of paper, Fermi estimated the yield of the Trinity atomic bomb test to within a factor of 2! Likewise, we can use the equation to get a reasonable estimate for the lifetime of a phenomenon.

There are two important lessons, one technical, one philosophical, from using the Copernican Principle to find out how long something will be around:

- We can use statistics to quickly obtain objective estimates which are not subject to human factors. (Also, statistics can be enjoyable!)

- A good first approximation of how long something will last is how long it has already lasted

With regards to the first point, if you want to figure out how long a Broadway show will run, where do you even start gathering data? You could look at reviews, actors’ reputations, or even the dialogue in the script to determine the appeal and figure out how much longer the show will go on. Or, you could do as Gott did, apply his simple equation, and correctly predict the runtimes of 42 out of 44 shows on Broadway.

When we think about the individual data points, it’s easy to get lost in the details and mis-interpret some aspect of human behavior. Sometimes, we need to take a step back, abstract away all the details, and apply basic statistics instead of trying to figure out human psychology.

On the latter point, as Nassim Taleb points out in his book Antifragile, the easiest way to figure out how long a non-perishable item — such as an idea or a work of art — will be around is to look at its current lifetime. In other words, the future lifetime of a technology is proportional to its past lifetime.

This is known as the Lindy Effect and makes sense with a little thought: a concept that has been around for a long time — books as a medium for exchanging information — must have a reason for surviving so long, and we can expect it to persist far into the future. On the other hand, a new idea— Google Glass — is statistically unlikely to survive because of the vast number of new concepts arising every single day.

Moreover, companies that have been around for 100 years — Caterpillar — must be doing something right and we can expect them to be around longer than startups — Theranos — which have not demonstrated they fulfill a need.

For one more telling example of the Copernican Lifetime Equation, consider the brilliant tweet you sent an hour ago. Statistics tell us this will be relevant for between 90 more seconds to a little less than 2 days. On the other hand, by bored students at least 26 years from now and up to 39,000 years in the future. What’s more, this story won’t be experienced in virtual reality — consumer virtual reality having between 73 days and 311 more years — but on the most durable form of media, books, which have 29.5 to 45000 years of dominance left.

Some people may view the Copernican Principle — both temporal and spatial — as a tragedy, but I find it exciting. Much as we realized the stunning grandeur of the universe only after we discarded the geocentric model, once we let go of the myth that our time is special and that we exist at the pinnacle of humanity, the possibilities are vast. Yes, we may be insignificant on a cosmic scale now, but 5000 years from now our ancestors — or possibly us — will expand throughout and even fundamentally alter the Milky Way.

As David Deutsch points out in his book The Fabric of Reality, anything not prohibited by the laws of physics will be achieved by humans given enough time. Instead of worrying that the job you’re supposed to be doing now is meaningless, think of it as contributing to the great endeavor upon which humanity has embarked. We are currently subject to the Copernican Principle, but maybe humans really are different: after all, we are starstuff that has evolved the ability to contemplate our place in the universe.

Sources:

- Implications of the Copernican Principle for Our Future Prospects

- How to Predict Everything

- We Have a Pretty Good Idea of When Humans Will Go Extinct

- The Copernican Principle: How to Predict Anything

Derivation

The derivation of the Copernican Lifetime Equation is as follows. The total lifetime of anything is the current lifetime plus the future lifetime:

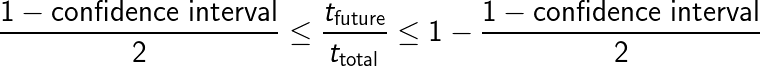

If we don’t believe our temporal location is privileged, then our observation of a phenomenon occurs neither at the beginning nor the end:

Make the following substitution for z:

Insert the definition of the total lifetime to get:

Then solve for the future lifetime of any phenomenon:

With a confidence interval of 95%, we get the multiplicative factors 1/39 and 39; with a confidence interval of 50%, the factors are 1/3 and 3; for 99% confidence, our factors become 1/199 and 199.

You can play around with the equations in this Jupyter Notebook. Also, take a look at the original paper by Gott for more details.

As always, I welcome constructive criticism and feedback. I can be reached on Twitter @koehrsen_will.