Screw The Environment But Consider Your Wallet

image source: Levi Brown

image source: Levi Brown

When the Health of the Environment and the Health of Your Wallet Align

According to Malcolm Gladwell’s bestselling nonfiction work Outliers, it takes 10,000 hours to achieve world-class expertise in a field such as playing an instrument or becoming a professional athlete. Based on this logic, one LED lightbulb could accompany you through the process of becoming a concert-level piano player, learning to speak French like a native, and then halfway to making it as a professional tennis player. As incredible as it may seem, the average LED lightbulb is rated to last for a minimum of 25,000 hours, or in practical terms, 22.8 years at 3 hours of usage per day. If you want the same duration of light from incandescent bulbs with an average lifetime of 1,000 hours, you will have to interrupt your studying to swap bulbs 25 times.

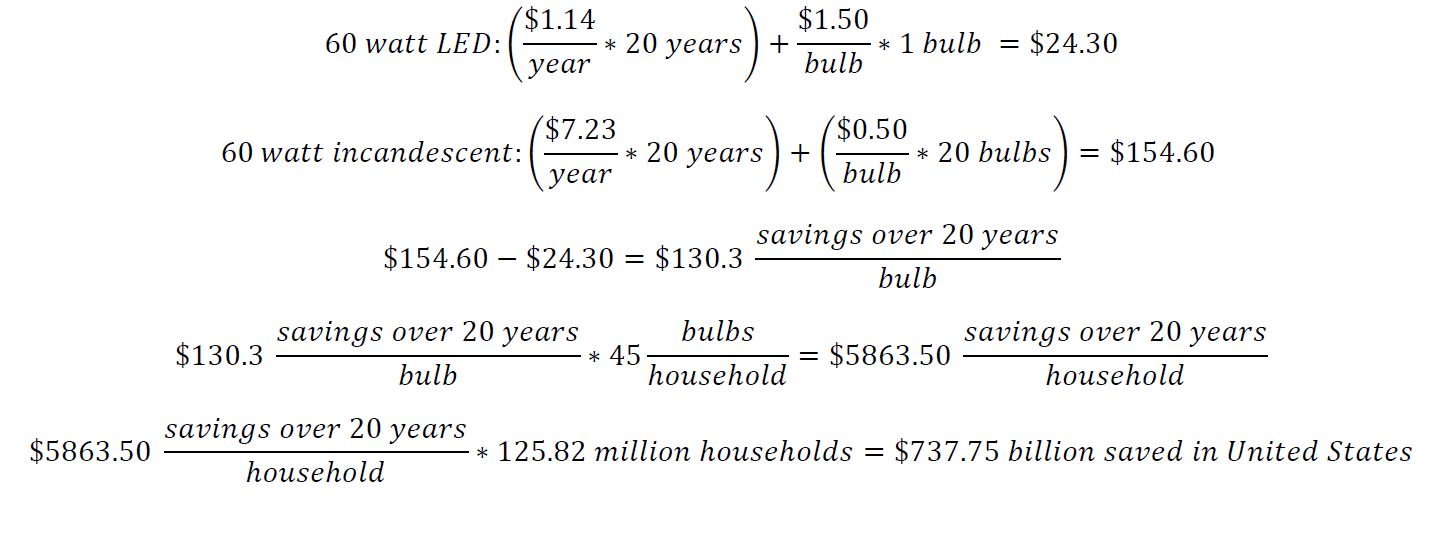

You have probably seen LED lightbulbs and even thought about making the switch on your last trip to the local hardware store. However, like many of us, you were probably put off by the high cost of LEDs and decided to stick with the same incandescent bulb that Thomas Edison would still recognize over 130 years after its invention (I have to mention that Edison did not invent the lightbulb but only figured out how to sell them in the classic example of the value of a good marketing campaign). Why pay up to 10 times the price for a bulb that produces the exact same amount of light? On my latest trip to Ace, I decided to work out if I was missing anything by not making the switch to LED. Quickly, I realized the enormous short-sighted error I was making. Take the humble and ubiquitous 60-watt lightbulb. My choice seemed relatively simple; I could pick up an incandescent for $0.50 (a 20-pack was just $10) or I could get a 60-watt equivalent LED bulb for $1.50 (4 for $6). The price discrepancy was much lower than I remembered from a couple years ago, but the LED was still 3 times the up-front price. Nevertheless, to get the full story, I did the simple math to work out the lifetime cost of each bulb. The LED, while putting out the exact same light intensity and color, uses only 9.5 watts which equates to $1.14 in electricity costs per year (based on 3 hours/day). Meanwhile, the incandescent bulb only converts 2.2% of the energy it receives into usable light (the rest is lost as heat) and consequently costs $7.23/year. Let’s see what that equates to over the lifetime of the bulb. I’ll go easy on the incandescent and assume that the LED lasts for only 20 years. The total cost to purchase and operate the 60-watt LED bulb for two decades works out to $24.30. The same light production from incandescent bulbs, which last for only a year of daily use, will require 20 bulbs and cost $154.60. (An interesting side note is that early incandescent lightbulb manufacturers formed a cartel and limited the lifetime of bulbs in order to sell larger quantities). That means a single LED bulb will save you over $130 over its two-decade lifetime. Standing in the hardware store, I had what can only be described as an epiphany as I realized how much cash I had been throwing away through short-term thinking.

Now, perhaps that is not persuasive enough. What’s $130 spread out over 20 years worth to you? I knew that I could not stop my analysis at merely a single bulb. Based on surveys, the average American household has 45 lightbulbs in daily use (take a moment to go and count. I was astonished to discover this was actually the case). Assuming these average out to 60 watts each, switching to all LEDs will save $490 in energy costs each year. That works out to a staggering total of $5863.50 over the next two decades. If pocketing a free six grand is not an enticement, imagine having to replace all 900 of those incandescents compared to the one-time installation of the 45 LEDs. Taking matters as far as we can, let’s consider the 126 million households in the United States. If all incandescent bulbs were switched to LEDs today (perhaps we can have a one-time national lightbulb switching holiday?), over the next 20 years, US households would save almost $740 billion and 111 billion lightbulbs.

Oftentimes, when it comes to talking about climate change, either the narratives are so depressing that people lose hope and believe their individual actions to be meaningless, or the audience is not responsive to environmental arguments and unwilling to make lifestyle changes for some intangible benefits at some point in the distant future. The light bulb example is not some abstract calculation involving megatons of CO2 reduced or inches of sea level rise prevented 150 years from now. It is about you being able to afford one (or perhaps two) more family vacations over the next 20 years because you made the simple step of changing your light bulbs. This is about real money staying in American pockets rather than lining the walls of a Saudi Arabian oil tycoon (or in reality buying another mansion for an Exxon CEO). Who is going to make the extra effort of recycling or incur the added cost of buying an electric car if the effects will not be felt for generations? However, when it comes to making personal or household decisions, you will find that the environmentally sound choice often aligns with the best interests of your wallet. Switching lightbulbs might be the most actionable example, but there are plenty of others from eating less meat to walking more (both of which will not only improve your health and that of the environment, but also cost far less over the long term than the alternative). The problem with these decisions is that, as in the case of LED lightbulbs, the upfront costs of implementing a change can obscure the benefits of a smart investment. Of course, I encourage anyone to consider the lasting impact to the Earth when making a purchasing decision or changing daily habits, but if that does not appeal to you, then I urge you to take the time to figure out the true economic cost of the options. More often than not, you will find that “saving the environment” aligns nicely with keeping your wallet “full of Benjamins.”

Author’s Note:

I was inspired to write this post after my experience a few months ago with a house owner from whom I was renting. I noticed that every single bulb in his house was incandescent and he kept them on almost constantly. After hearing him complain yet another time that he had to replace the darn things twice a year, I decide to make the polite suggestion that LEDs were a better choice for the environment. He scoffed and said (although not so politely): “Screw the environment. That’s not for me to worry about; I’m sure the polar bears can find somewhere else to live.” (He did refrain from calling me a socialist environmental-terrorist which I thought was a nice gesture). I took a while off from the topic and thought about my approach. The next time the issue came up when another two bulbs had burned out, I made the LED suggestion again, but this time I couched my recommendation in cold economic terms. I mentioned the cost-savings and the lifetime advantage of LEDs, and reluctantly he agreed to make the switch in several fixtures. After a month with the new bulbs, he was prepared to accept that they did indeed produce the same comforting light as incandescents and of course none had burned out. At that point, he decided to go full in (this was not a man to do anything halfway) and replaced every single bulb in his house with LEDs. After two months with no complaints and not a single replacement, I thought nothing more of the matter. Then, one day, he triumphantly pulled out his electricity bills and showed me the year-over-year comparisons by month. His electricity costs had decreased by an astounding $40 per month under the same exact conditions and with no conscious effort on his part to reduce usage. He said that he had even convinced many of his friends (all people to whom saving the environment was about as meaningful as taking a vacation to Jupiter) to do the same and he had heard only positive responses. At this point, it finally dawned on me, people may not care about conserving natural resources, but when it comes to an economic argument, there can be no reason to campaign for less money in American pockets. Now, any time an environmental subject arises, I keep all of my arguments in terms of proven economic facts. I have found that people from all backgrounds are receptive to this approach and it often leads to productive dialogue about addressing climate change to order to strengthen the economy (for example by reducing dependence on foreign energy sources). I am optimistic about the future of renewable energy not because people are suddenly going to become tree-hugging environmentalists, but because new installations of renewable energy can now compete on a level playing field with fossil fuels. Rick Perry did not make Texas into the US leader in wind energy because he wants to preserve the Earth for his grandchildren, he did it because it made economic sense. There are numerous challenges remaining in the switch to renewable energy, and I do not claim that technological progress will inevitably save us. Instead, I see reason to be optimistic that economic realities can accelerate the world’s move to sustainable energy production.

Will

Sources: Lightbulb data was compiled by the author from the Ace Hardware Store in Ames, Iowa. All other sources used are linked in the article itself. Math calculations follow below: