How To Master New Skills

Why trying to avoid spreadsheets is the best way to learn data science

The best way to learn a new skill is using it to solve problems. In my previous life as an aerospace engineering student, I spent hours writing complicated formulas in Excel to do everything from designing wings to calculating reentry angles of spacecraft. After hours of labor, I would present results in the bland Excel charts that dominate so many powerpoints. Convinced this was not an optimal workflow, I decided to learn Python, a common coding language, solely to avoid spending all my waking hours in Excel.

With the help of Automate the Boring Stuff with Pythonby Al Sweigart, I picked up enough of the language to cut the time I spent in Excel by 90%. Rather than memorizing the basics, I focused on efficiently solving aerospace problems. I was soon flying through assignments, and when I presented Python graphs in class, I was asked what sort of magic techniques I used. Without even trying, I gained a reputation as someone who could take a tangled spreadsheet and turn the data into illuminating images.

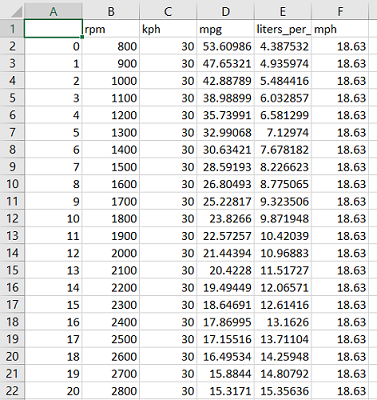

The difference between data (left) and knowledge (right)

The difference between data (left) and knowledge (right)

Ironically, it was only when I had reached the top of my field that I decided to make the switch to data science. While working as an aerospace engineer intern at NASA, I was surrounded by some of the brightest people in the country. However, these individuals’ brilliance was severely constrained because they ended up spending most of their time poring over that curse of modern data: Excel spreadsheets. These were people working on expanding humanity’s knowledge of the universe literally doing rocket science in spreadsheets! It was at this moment that I realized I would have a greater impact as a data scientist helping people make sense from data than as an aerospace engineer.

Although I was working on a mission to send a satellite into space (Near-Earth Asteroid Scout), I was frustrated with the work because it mostly involved hours of paging through numbers. Often, these spreadsheets had been used for years and people trusted the numbers despite not being able to understand the formulas. I eventually gave up trying to comprehend the spreadsheets and instead set about automating calculations using the little bit of Python I knew. Building on my limited knowledge I had from trying to escape spreadsheets in school, and using some code I copied and pasted from Stack Overflow, I was able to increase my work efficiency and quality.

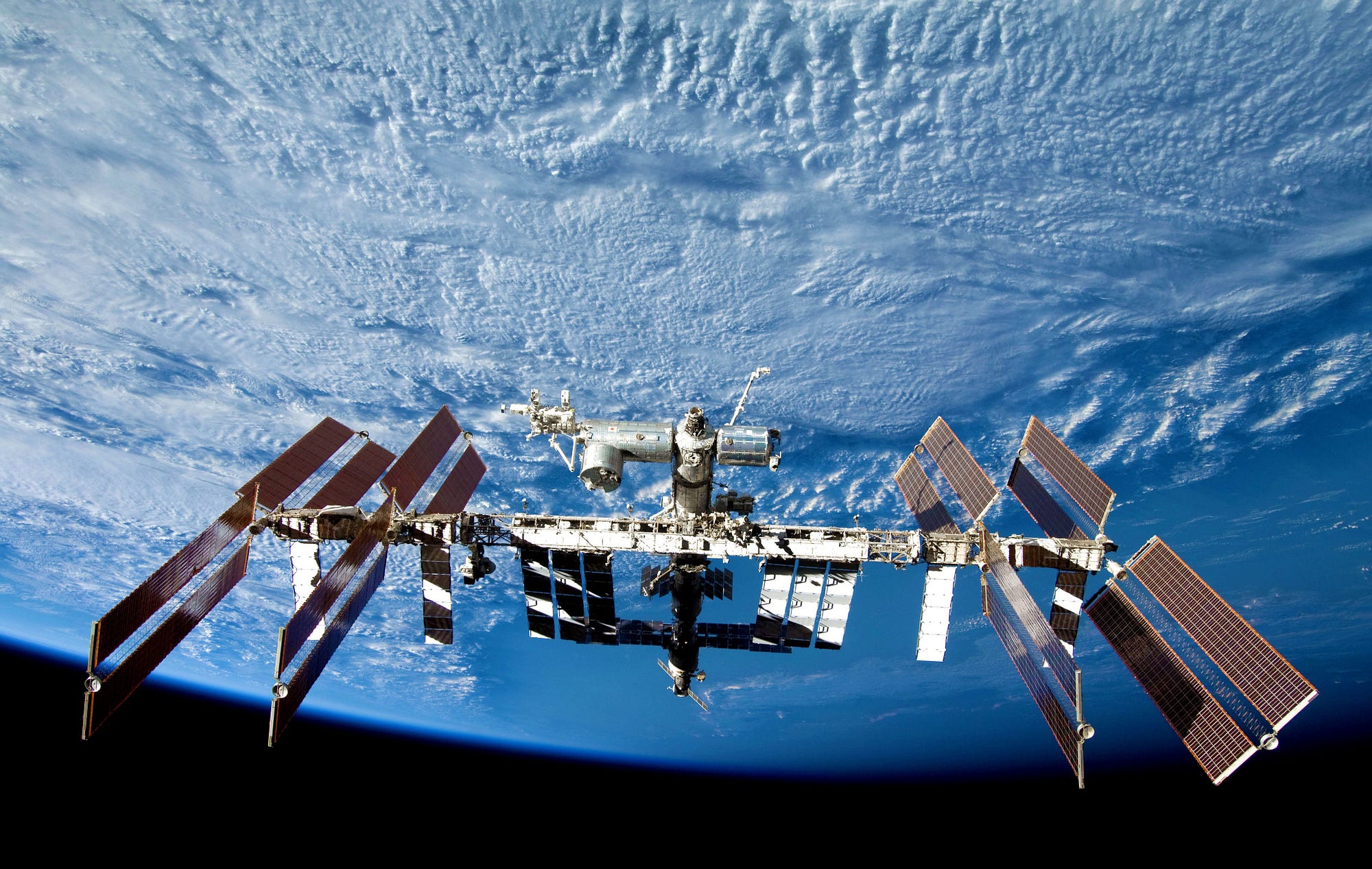

Not pictured: the millions of lines of Excel behind the ISS

Not pictured: the millions of lines of Excel behind the ISS

Tentatively, I mentioned to colleagues there was a better way to do their work. Although they were skeptical, they had seen my results, and were willing to listen. After showing them a few examples where I wrote simple code to replace editing spreadsheets by hand, they began to embrace the idea. At first, I wrote the scripts for them, a task I was happy to take on because my workload had been greatly reduced by a few lines of code, but eventually they were able to start writing their own scripts. (Although I did convince them to write code, it was almost always in Matlab or even Fortran. There are some things you just can’t change!) Over the course of a few weeks, I was transformed from a lowly intern into the go-to data consultant for my branch.

This real-world application illustrates two critical points:

- New skills are learned from solving problems not from theory

- It doesn’t take much knowledge to achieve useful results

Contrary to the traditional model of education, we first develop applications and then form theories, not the other way round. The internal combustion engine, one of the most influential technologies in history, came out of decades of tinkering by engineers not from theoreticians. Only after the engine had been invented did the theories underlying how it worked fall into place. I learned programming and data science not by memorizing the details of data structures and formulas, but by writing code to solve problems. Along the way, I picked up plenty of the basic knowledge I could have read in books. Now when I learn a new machine learning method, I go straight to using it on real data instead of studying the formulas. I get a better understanding of how a model works by seeing it in action instead of on the page.

Theory vs Application. Only one actually flies.

Theory vs Application. Only one actually flies.

People usually think they need to be experts in a field before they can contribute. This prevents them from even starting to learn a new technique because they imagine it will be years before it will be useful. My experience with NASA provides a counterexample to this misconception. A limited amount of the correct knowledge, in this case data science, can be extremely influential. Rather than waiting until I knew everything possible about coding, I applied what I did know with beneficial results.

The cliché that Rome was not built in a day implies large projects require years of work. However, there is a more important message here: an entire city does not need to be built before it is useful. Even with a few homes, a city still serves a purpose. Half of Rome is better than no Rome, just as some knowledge is preferable to no knowledge. Every new house built or every additional piece of knowledge inspires more growth in a positive feedback cycle. The key is to keep solving problems during the learning process instead of waiting until you master a subject to use it!

These ideas should be encouraging to anyone wanting to pick up a new skill or switch fields. If you think it will take too long to learn a technique, or you are bored by the basics, don’t worry! The simple stuff is tedious and you’re better off learning by working on problems and picking up the fundamentals along the way. Furthermore, realize you can start getting useful results with a limited amount of the right knowledge. Solve a few basic problems and improve your skills as required when the complexity increases.

Since we already used one cliché, here’s another: “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is today.” Don’t regret not learning programming — or any skill — while in school, but think about what you want to know in the future! Figure out the problems you (or your colleagues) need to solve and start learning. Looking back at it now, my road to data science was not smoothly planned, but evolved by solving problems and steadily acquiring tools. There has never been a better age to teach yourself anything, and the best way to expand your skill-set is to start working on problems!

As always, I welcome feedback and constructive criticism. I can be reached on Twitter @koehrsen_will.

I would like to thank Taylor Koehrsen (PharmD no less!) for her editing help.