A Data Science for Good Machine Learning Project Walk-Through in Python: Part One

Solving a complete machine learning problem for societal benefit

Data science is an immensely powerful tool in our data-driven world. Call me idealistic, but I believe this tool should be used for more than getting people to click on ads or spend more time consumed by social media.

In this article and the sequel, we’ll walk through a complete machine learning project on a “Data Science for Good” problem: predicting household poverty in Costa Rica. Not only do we get to improve our data science skills in the most effective manner — through practice on real-world data — but we also get the reward of working on a problem with social benefits.

It turns out the same skills used by companies to maximize ad views can also be used to help relieve human suffering.

The full code is available as a Jupyter Notebook both on Kaggle (where it can be run in the browser with no downloads required) and on GitHub. This is an active Kaggle competition and a great project to get started with machine learning or to work on some new skills.

Problem and Approach

The Costa Rican Household Poverty Level Prediction challenge is a data science for good machine learning competition currently running on Kaggle. The objective is to use individual and household socio-economic indicators to predict poverty on a household basis. IDB, the Inter-American Development Bank, developed the problem and provided the data with the goal of improving upon traditional methods for identifying families at need of aid.

The Costa Rican Poverty Prediction contest is currently running on Kaggle.

The Costa Rican Poverty Prediction contest is currently running on Kaggle.

The poverty labels fall into four levels making this a supervised multi-class classification problem:

- Supervised: given the labels for the training data

- Multi-Class Classification: labels are discrete with more than 2 values

The general approach to a machine learning problem is:

- Understand the problem and data descriptions

- Data cleaning / exploratory data analysis

- Feature engineering / feature selection

- Model comparison

- Model optimization

- Interpretation of results

While these steps may seem to present a rigid structure, the machine learning process is non-linear, with parts repeated multiple times as we get more familiar with the data and see what works. It’s nice to have an outline to provide a general guide, but we’ll often return to earlier parts of the process if things aren’t working out or as we learn more about the problem.

We’ll go through the first four steps at a high-level in this article, taking a look at some examples, with the full details available in the notebooks. This problem is a great one to tackle both for beginners — because the dataset is manageable in size — and for those who already have a firm footing because Kaggle offers an ideal environment for experimenting with new techniques.

The last two steps, plus an experimental section, can be found in part two.

Understanding the Problem and Data

In an ideal situation, we’d all be experts in the problem subject with years of experience to inform our machine learning. In reality, we often work with data from a new field and have to rapidly acquire knowledge both of what the data represents and how it was collected.

Fortunately, on Kaggle, we can use the work shared by other data scientists to get up to speed relatively quickly. Moreover, Kaggle provides a discussion platform where you can ask questions of the competition organizers. While not exactly the same as interacting with customers at a real job, this gives us an opportunity to figure out what the data fields represent and any considerations we should keep in mind as we get into the problem.

Some good questions to ask at this point are:

- Are there certain variables that are considered most important for this problem according to the domain experts?

- Are there known issues with the data? Certain values / anomalies to look out for?

- How was the data collected? If there are outliers, are they likely the result of human error or extreme but still valid data?

For example, after engaging in discussions with the organizers, the community found out the text string “yes” actually maps to the value 1.0 and that the maximum value in one of the columns should be 5 which can be used to correct outliers. We would have been hard-pressed to find out this information without someone who knows the data collection process!

Part of data understanding also means digging into the data definitions. The most effective way is literally to go through the columns one at a time, reading the description and making sure you know what the data represents. I find this a little dull, so I like to mix this process with data exploration, reading the column description and then exploring the column with stats and figures.

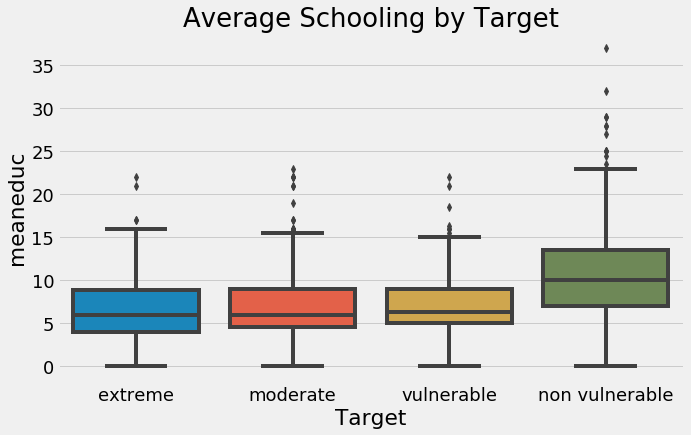

For example, we can read that meaneduc is the average amount of education in the family, and then we can plot it distributed by the value of the label to see if it has any noticeable differences between the poverty level .

Average schooling in family by target (poverty level).

Average schooling in family by target (poverty level).

This shows that families the least at risk for poverty — non-vulnerable — tend to have higher average education levels than those most at risk. Later in feature engineering, we can use this information by building features from the education since it seems to show a different between the target labels.

There are a total of 143 columns (features), and while for a real application, you want to go through each with an expert, I didn’t exhaustively explore all of these in the notebook. Instead, I read the data definitions and looked at the work of other data scientists to understand most of the columns.

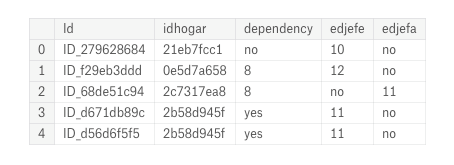

Another point to establish from the problem and data understanding stage is how we want to structure our training data. In this problem, we’re given a single table of data where each row represents an individual and the columns are the features. If we read the problem definition, we are told to make predictions for each household which means that our final training dataframe (and also testing) should have one row for each house. This point informs our entire pipeline, so it’s crucial to grasp at the outset.

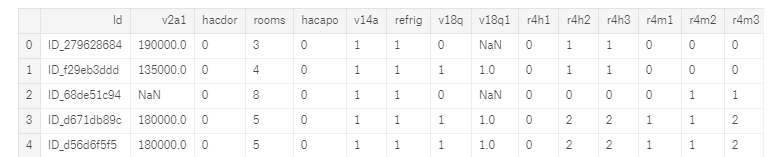

A snapshot of the data where each row is one individual.

A snapshot of the data where each row is one individual.

Determine the Metric

Finally, we want to make sure we understanding the labels and the metric for the problem. The label is what we want to predict, and the metric is how we’ll evaluate those predictions. For this problem, the label is an integer, from 1 to 4, representing the poverty level of a household. The metric is the Macro F1 Score, a measure between 0 and 1 with a higher value indicating a better model.The F1 score is a common metric for binary classification tasks and “Macro” is one of the averaging options for multi-class problems.

Once you know the metric, figure out how to calculate it with whatever tool you are using. For Scikit-Learn and the Macro F1 score, the code is:

from sklearn.metrics import f1_score

# Code to compute metric on predictions

score = f1_score(y_true, y_prediction, average = 'macro')

Knowing the metric allows us to assess our predictions in cross validation and using a hold-out testing set, so we know what effect, if any, our choices have on performance. For this competition, we are given the metric to use, but in a real-world situation, we’d have to choose an appropriate measure ourselves.

Data Exploration and Data Cleaning

Data exploration, also called Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA), is an open-ended process where we figure out what our data can tell us. We start broad and gradually hone in our analysis as we discover interesting trends / patterns that can be used for feature engineering or find anomalies. Data cleaning goes hand in hand with exploration because we need to address missing values or anomalies as we find them before we can do modeling.

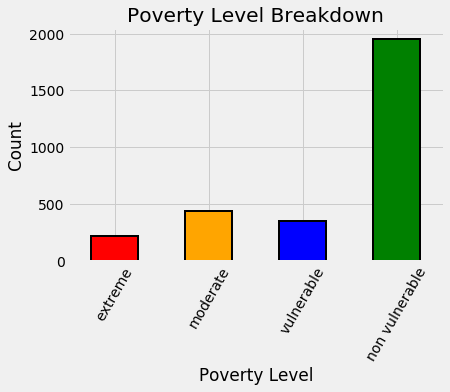

For an easy first step of data exploration, we can visualize the distribution of the labels for the training data (we are not given the testing labels).

Distribution of training labels.

Distribution of training labels.

Right away this tells us we have an imbalanced classification problem, which can make it difficult for machine learning models to learn the underrepresented classes. Many algorithms have ways to try and deal with this, such as setting class_weight = "balanced" in the Scikit-Learn random forest classifier although they don’t work perfectly. We also want to make sure to use stratified sampling with cross validation when we have an imbalanced classification problem to get the same balance of labels in each fold.

To get familiar with the data, it’s helpful to go through the different column data types which represent different statistical types of data:

float: These usually are continuous numeric variablesint: Usually are either Boolean or ordinal (discrete with an ordering)objectorcategory: Usually strings or mixed data types that must be converted in some manner before machine learning

I’m using statistical type to mean what the data represents — for example a Boolean that can only be 1 or 0 — and data type to mean the actual way the values are stored in Python such as integers or floats. The statistical type informs how we handle the columns for feature engineering.

(I specified usually for each data type / statistical type pairing because you may find that statistical types are saved as the wrong data type.)

If we look at the integer columns for this problem, we can see that most of them represent Booleans because there are only two possible values:

Integer columns in data.

Integer columns in data.

Going through the object columns, we are presented with a puzzle: 2 of the columns are Id variables (stored as strings), but 3 look to be numeric values.

# Train is pandas dataframe of training data

train.select_dtypes('object').head()

Object columns in original data.

Object columns in original data.

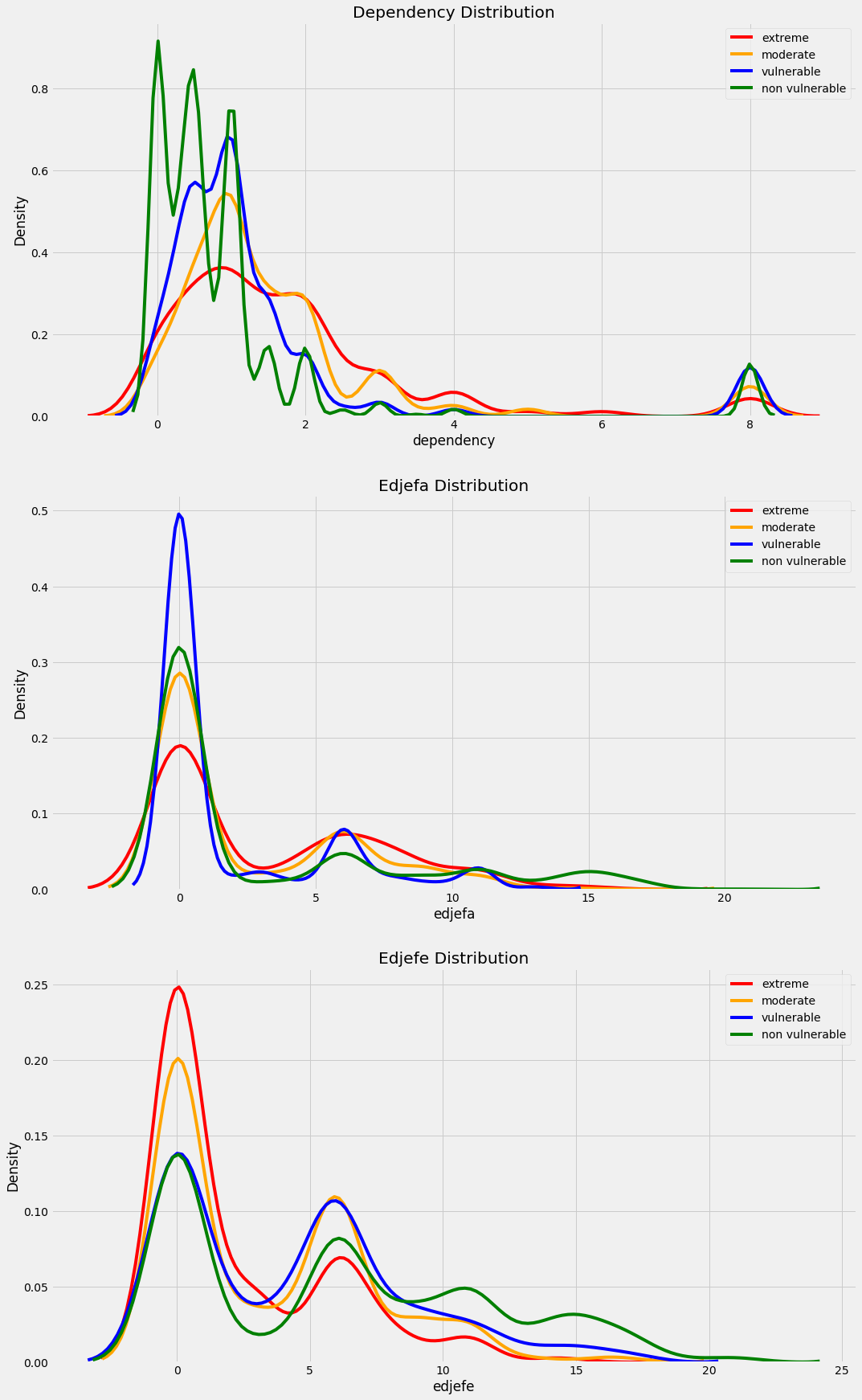

This is where our earlier data understanding comes into play. For these three columns, some entries are “yes” and some are “no” while the rest are floats. We did our background research and thus know that a “yes” means 1 and a “no” means 0. Using this information, we can correct the values and then visualize the variable distributions colored by the label.

Distribution of corrected variables by the target label.

Distribution of corrected variables by the target label.

This is a great example of data exploration and cleaning going hand in hand. We find something incorrect with the data, fix it, and then explore the data to make sure our correction was appropriate.

Missing Values

A critical data cleaning operation for this data is handling missing values. To calculate the total and percent of missing values is simple in Pandas:

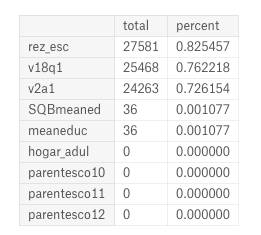

Missing Values in Data

Missing Values in Data

In some cases there are reasons for missing values: the v2a1 column represents monthly rent and many of the missing values are because the household owns the home. To figure this out, we can subset the data to houses missing the rent payment and then plot the tipo_ variables (I’m not sure where these column names come from) which show home ownership.

Home ownership status for those households with no rent payments.

Home ownership status for those households with no rent payments.

Based on the plot, the solution is to fill in the missing rent payments for households that own their house with 0 and leave the others to be imputed. We also add a boolean column that indicates if the rent payment was missing.

The other missing values in the columns are dealt with the same way: using knowledge from other columns or about the problem to fill in the values, or leaving them to be imputed. Adding a boolean column to indicate missing values can also be useful because sometimes the information that a value was missing is important. Another crucial point to note is that for missing values, we often want to think about using information in other columns to fill in missing values such as we did with the rent payment.

Once we’ve handled the missing values, anomalies, and incorrect data types, we can move on to feature engineering. I usually view data exploration as an ongoing process rather than one set chunk. For example, as we get into feature engineering, we might want to explore the new variables we create.

The data science process is non-linear: while we have a general outline, we often go back and redo previous steps as we get deeper into the problem.

Feature Engineering

If you follow my work, you’ll know I’m convinced automated feature engineering — with domain expertise — will take the place of traditional manual feature engineering. For this problem, I took both approaches, doing mostly manual work in the main notebook, and then writing another notebook with automated feature engineering. Not surprisingly, the automated feature engineering took one tenth the time and achieved better performance! Here I’ll show the manual version, but keep in mind that automated feature engineering (with Featuretools) is a great tool to learn.

In this problem, our primary objective for feature engineering is to aggregate all the individual level data at the household level. That means grouping together the individuals from one house and then calculating statistics such as the maximum age, the average level of education, or the total number of cellphones owned by the family.

Fortunately, once we have separated out the individual data (into the ind dataframe), doing these aggregations is literally one line in Pandas (with idhogar the household identifier used for grouping):

# Aggregate individual data for each household

ind_agg = ind.groupby('idhogar').agg(['min', 'max', 'mean', 'sum'])

After renaming the columns, we have a lot of features that look like:

Features produced by aggregation of individual data.

Features produced by aggregation of individual data.

The benefit of this method is that it quickly creates many features. One of the drawbacks is that many of these features might not be useful or are highly correlated (called collinear) which is why we need to use feature selection.

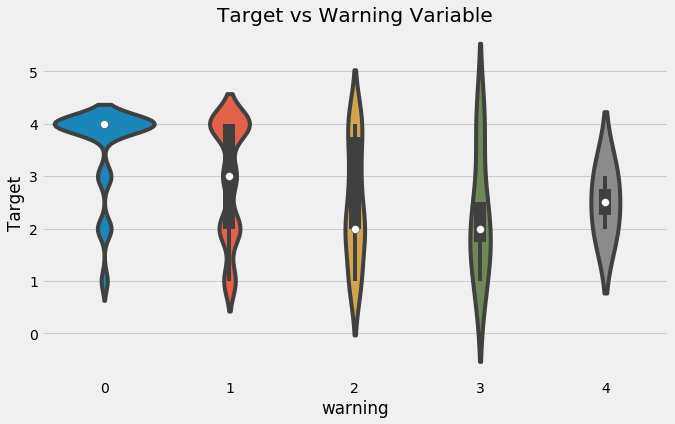

An alternative method to aggregations is to calculate features one at a time using domain knowledge based on what features might be useful for predicting poverty. For example, in the household data, we create a feature called warning which adds up a number of household “warning signs” ( house is a dataframe of the household variables):

# No toilet, no electricity, no floor, no water service, no ceiling

house['warning'] = 1 * (house['sanitario1'] +

(house['elec'] == 0) +

house['pisonotiene'] +

house['abastaguano'] +

(house['cielorazo'] == 0))

Violinplot of Target by Warning Value.

Violinplot of Target by Warning Value.

We can also calculate “per capita” features by dividing one value by another ( tamviv is the number of household members):

# Per capita features for household data

house['phones-per-capita'] = house['qmobilephone'] / house['tamviv']

house['tablets-per-capita'] = house['v18q1'] / house['tamviv']

house['rooms-per-capita'] = house['rooms'] / house['tamviv']

house['rent-per-capita'] = house['v2a1'] / house['tamviv']

When it comes to manual vs automated feature engineering, I think the optimal answer is a blend of both. As humans, we are limited in the features we build both by creativity — there are only so many features we can think to make — and time — there is only so much time for us to write the code. We can make a few informed features like those above by hand, but where automated feature engineering excels is when doing aggregations that can automatically build on top of other features.

The best approach is to spend some time creating a few features by hand using domain knowledge, and then hand off the process to automated feature engineering to generate hundreds or thousands more.

(Featuretools is the most advanced open-source Python library for automated feature engineering. Here’s an article to get you started in about 10 minutes.)

Feature Selection

Once we have exhausted our time or patience making features, we apply feature selection to remove some features, trying to keep only those that are useful for the problem. “Useful” has no set definition, but there are some heuristics (rules of thumb) that we use to select features.

One method is by determining correlations between features. Two variables that are highly correlated with one another are called collinear. These are a problem in machine learning because they slow down training, create less interpretable models, and can decrease model performance by causing overfitting on the training data.

The tricky part about removing correlated features is determining the threshold of correlation for saying that two variables are too correlated. I generally try to stay conservative, using a correlation coefficient in the 0.95 or above range. Once we decide on a threshold, we use the below code to remove one out of every pair of variables with a correlation above this value:

We are only removing features that are correlated with one another. We want features that are correlated with the target(although a correlation of greater than 0.95 with the label would be too good to be true)!

There are many methods for feature selection (we’ll see another one in the experimental section near the end of the article). These can be univariate — measuring one variable at a time against the target — or multivariate — assessing the effects of multiple features. I also tend to use model-based feature importances for feature selection, such as those from a random forest.

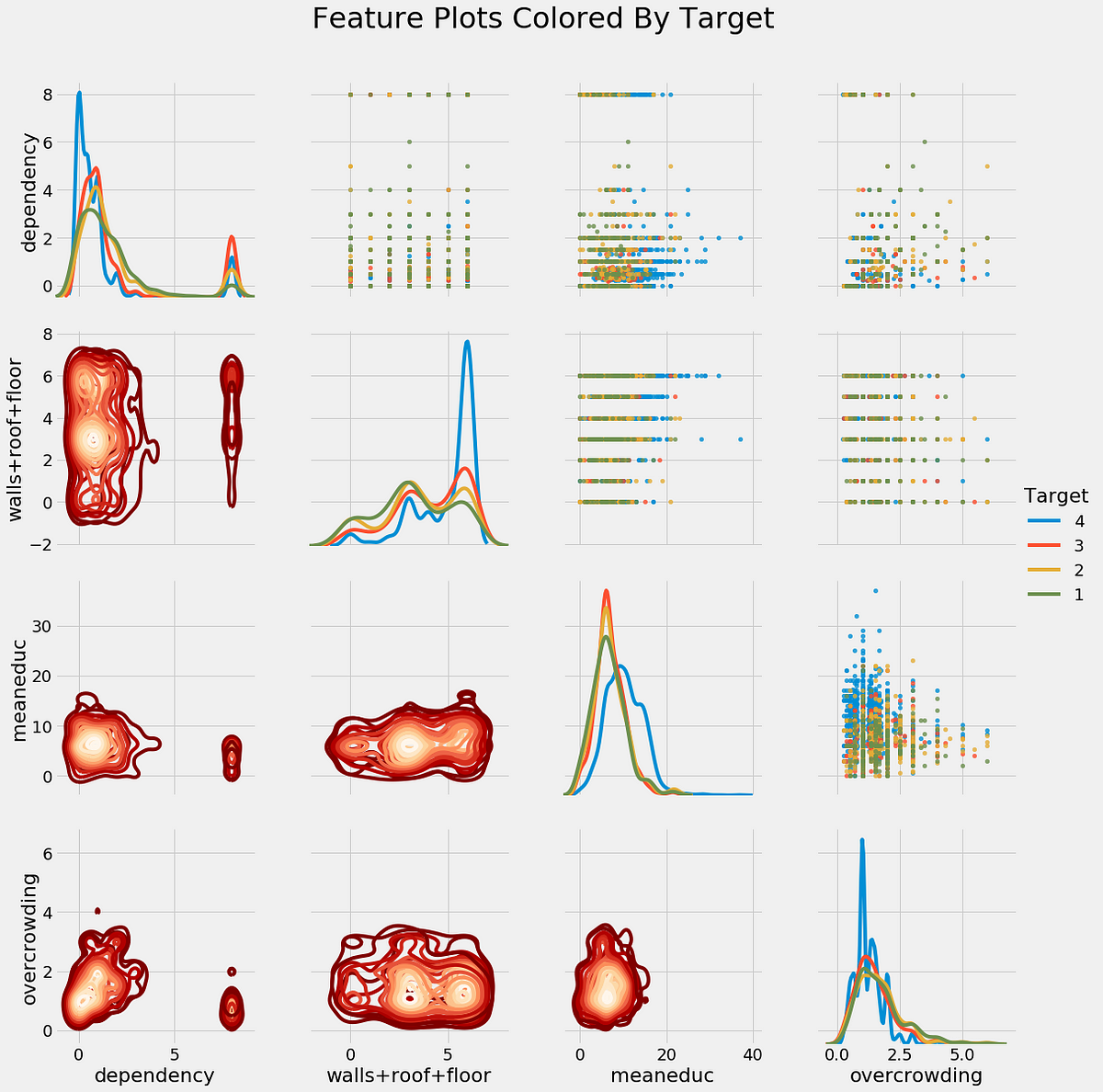

After feature selection, we can do some exploration of our final set of variables, including making a correlation heatmap and a pairsplot.

Correlation heatmap

Correlation heatmap

Pairsplot colored by the value of the label (bottom).

Pairsplot colored by the value of the label (bottom).

One point we get from the exploration is the relationship between education and poverty: as the education of a household increases (both the average and the maximum), the severity of poverty tends to decreases (1 is most severe):

Max schooling of the house by target value.

Max schooling of the house by target value.

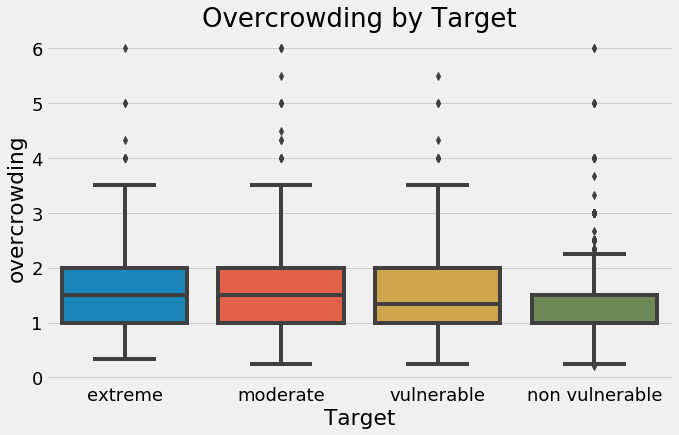

On the other hand, as the level of overcrowding — the number of people per room — increases, the severity of the poverty increases:

Household overcrowding by value of the target.

Household overcrowding by value of the target.

These are two actionable insights from this competition, even before we get to the machine learning: households with greater levels of education tend to have less severe poverty, and households with more people per room tend to have greater levels of poverty. I like to think about the ramifications and larger picture of a data science project in addition to the technical aspects. It can be easy to get overwhelmed with the details and then forget the overall reason you’re working on this problem.

The ultimate goal of this project is to figure out how to predict poverty to most effectively get help to those in need.

Model Comparison

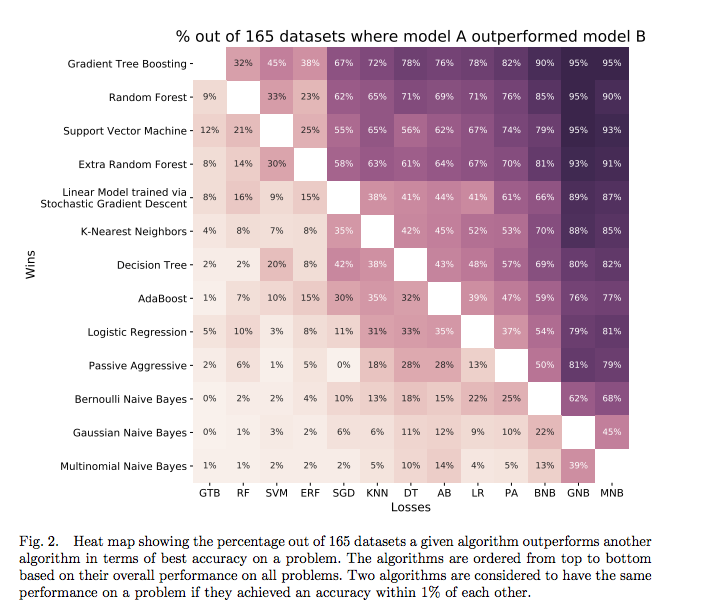

The following graph is one of my favorite results in machine learning: it displays the performance of machine learning models on many datasets, with the percentages showing how many times a particular method beat any others. (This is from a highly readable paper by Randal Olson.)

Comparison of many algorithms on 165 datasets.

Comparison of many algorithms on 165 datasets.

What this shows is that there are some problems where even a simple Logistic Regression will beat a Random Forest or Gradient Boosting Machine. Although the Gradient Tree Boosting model generally works the best, it’s not a given that it will come out on top. Therefore, when we approach a new problem, the best practice is to try out several different algorithms rather than always relying on the same one. I’ve gotten stuck using the same model (random forest) before, but remember that no one model is always the best.

Fortunately, with Scikit-Learn, it’s easy to evaluate many machine learning models using the same syntax. While we won’t do hyperparameter tuning for each one, we can compare the models with the default hyperparameters in order to select the most promising model for optimization.

In the notebook, we try out six models spanning the range of complexity from simple — Gaussian Naive Bayes — to complex — Random Forest and Gradient Boosting Machine. Although Scikit-Learn does have a GBM implementation, it’s fairly slow and a better option is to use one of the dedicated libraries such as XGBoost or LightGBM. For this notebook, I used Light GBM and choose the hyperparameters based on what have worked well in the past.

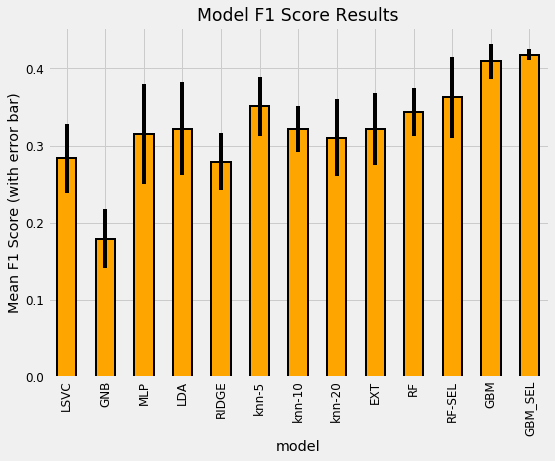

To compare models, we calculate the cross validation performance on the training data over 5 or 10 folds. We want to use the training data because the testing data is only meant to be used once as an estimate of the performance of our final model on new data. The following plot shows the model comparison. The height of the bar is the average Macro F1 score over the folds recorded by the model and the black bar is the standard deviation:

Model cross validation comparison results.

Model cross validation comparison results.

(To see an explanation of the names, refer to the notebook. RF stands for Random Forest and GBM is Gradient Boosting Machine with SEL representing the feature set after feature selection). While this isn’t entirely a level comparison — I did not use the default hyperparameters for the Gradient Boosting Machine — the general results hold: the GBM is the best model by a large margin. This reflects the findings of most other data scientists.

Notice that we cross-validated the data before and after feature selection to see its effect on performance. Machine learning is still largely an empirical field, and the only way to know if a method is effective is to try it out and then measure performance. It’s important to test out different choices for the steps in the pipeline — such as the correlation threshold for feature selection — to determine if they help. Keep in mind that we also want to avoid placing too much weight on cross-validation results, because even with many folds, we can still be overfitting to the training data. Finally, even though the GBM was best for this dataset, that will not always be the case!

Based on these results, we can choose the gradient boosting machine as our model (remember this is a decision we can go back and revise!). Once we decide on a model, the next step is to get the most out of it, a process known as model hyperparameter optimization.

Recognizing that not everyone has time for a 30-minute article (even on data science) in one sitting, I’ve broken this up into two parts. The second part covers model optimization, interpretation, and an experimental section.

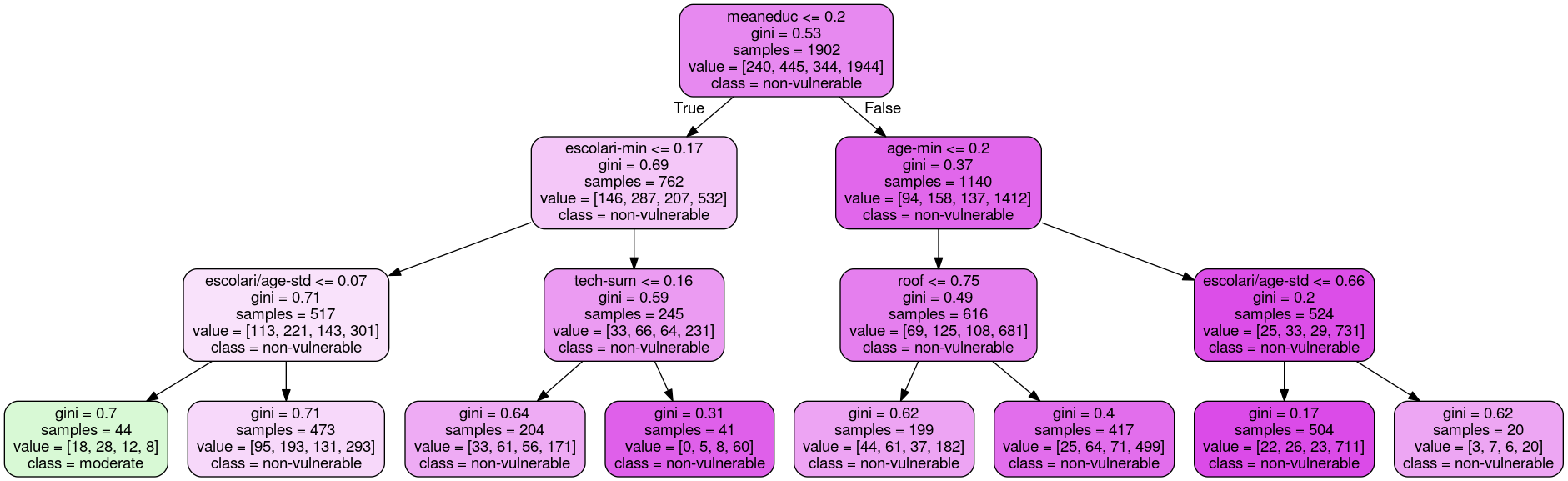

Decision tree visualization from part two.

Decision tree visualization from part two.

Conclusions

By this point, we can see how all the different parts of machine learning come together to form a solution: we first had to understand the problem, then we dug into the data, cleaning it as necessary, then we made features for a machine learning model, and finally we evaluated several different models.

We’ve covered many techniques and have a decent model (although the F1 score is relatively low, it places in the top 50 models submitted to the competition). Nonetheless, we still have a few steps left: through optimization, we can improve our model, and then we have to interpret our results because no analysis is complete until we’ve communicated our work.

As a next step, see part two, check out the notebook (also on GitHub), or get started solving the problem for yourself.

As always, I welcome feedback, constructive criticism, and hearing about your data science projects. I can be reached on Twitter @koehrsen_will.