NYSERDA Tenant Energy Data Challenge

Presented in this article are my answers to the NYSERDA Tenant Energy Data Challenge.

The GitHub Repo contains the code used in this project.

Problem Statements

1 What is your forecasted consumption across all 18 tenant usage meters for the 24 hours of 8/31/20 in 15 minute intervals (1728 predictions)?

The forecasted consumption is submitted as a csv to the challenge submission form.

2 How correlated are building-wide occupancy and tenant consumption?

For every 10% decrease in occupancy, the consumption is expected to decrease by 3.1%.

- While some tenant meters surprisingly show an increase in consumption with a reduction in occupancy, the majority display the expected decrease in consumption.

- We can quantify this observation by stating the percentage decrease in consumption for every percentage decrease in occupancy, which, averaged over all the tenant meters, is 0.31.

- For every 10% decrease in occupancy, the consumption is expected to decrease by 3.1%.

The below stats show the expected change in consumption (positive values indicate a decrease in consumption) for every 10% decrease in occupancy.

| Tenant Meter | Consumption Decrease for 10% Occupancy Decrease (%) |

|---|---|

| Average | 3.10 |

| 1-001 | 4.15 |

| 1-002 | 2.77 |

| 1-003 | 2.97 |

| 1-004 | 3.55 |

| 1-005 | 1.61 |

| 1-006 | 4.47 |

| 1-007 | 3.31 |

| 1-008 | 2.47 |

| 1-009 | 1.27 |

| 1-010 | 3.15 |

| 1-011 | 6.66 |

| 1-012 | -0.66 |

| 1-013 | -0.99 |

| 1-014 | 2.43 |

| 1-015 | 3.88 |

| 1-016 | 5.89 |

| 1-017 | 0.13 |

| 1-018 | 5.87 |

| Building | 3.05 |

On a technical note, the average Pearson’s correlation coefficient (a standard method of measuring correlations) between the building-wide reduction in occupancy and tenant consumption is 0.60, a strongly positive correlation (as the reduction in occupancy increases, the reduction in consumption increases). As an interesting note, this value is negative for some meters, which display an increase in consumption with decreases in occupancy.

3 What is the mean absolute error for your model?

The Mean Absolute Error is 0.095 kWh averaged over the tenant meters.

The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) is measured using one-day-ahead rolling validation. In this method, for each tenant meter, we:

- Select a “target” date

- Train a machine learning model on all the data before that date

- Predict the consumption for that target date

- Compare the forecasted consumption to the actual consumption

When we perform this operation on the 20 most recent dates for all tenant meters, we get an average MAE of 0.095 kWh.

The MAE for predicting the entire building’s consumption (with the ConEd Electric data) is 23.5 kWh, representing a 3.84% error on the 20 validation dates. That is, we can predict the building’s consumption on a given day with 96%+ accuracy at each 15-minute interval.

Below are the mean absolute errors for each tenant meter and for the entire building (from the ConEd Electric data)

| meter | Mean Absolute Error (kWh) |

|---|---|

| Average | 0.095 |

| 1-001 | 0.10 |

| 1-002 | 0.15 |

| 1-003 | 0.05 |

| 1-004 | 0.28 |

| 1-005 | 0.10 |

| 1-006 | 0.12 |

| 1-007 | 0.95 |

| 1-008 | 0.15 |

| 1-009 | 0.07 |

| 1-010 | 0.05 |

| 1-011 | 0.05 |

| 1-012 | 0.06 |

| 1-013 | 0.05 |

| 1-014 | 0.04 |

| 1-015 | 0.05 |

| 1-016 | 0.04 |

| 1-017 | 0.10 |

| 1-018 | 0.13 |

| Building | 23.5 |

4 What feature(s)/predictor(s) were most important in determining energy efficiency?

The most important features for predicting energy efficiency were:

- Time of day

- Most efficient in the late afternoon/evening

- Time since the start of covid

- Buildings got more efficient over time into June, then efficiency began declining in August

- Occupancy as a percent of the baseline

- Most efficient occupancy as 5% (90-100 tenants)

- Day of the week.

- Weekdays more efficient

The most efficient time of day during the week was the late afternoon, as it appears the building began shutting down equipment earlier than it did before covid. The start of equipment shutoff during covid was around 5:00 pm based on the declines in tenant and whole building meter consumption. Before covid, the reduction in consumption at the end of the day occurred later than 6:00 pm.

Although there are likely other factors at play, the most efficient operation occurred during May-June. The efficiency started lower in March and declined from July through August before plateauing. I hypothesize that, at first, building engineers were not sure how to operate most efficiently during covid, but, over time, they learned the best strategy as buildings remained empty. However, as buildings started re-occupying - even if only by a few percent - the building equipment began running harder to keep tenants comfortable.

The energy efficiency was higher during the week than on weekends which appears to be because the peak load during the day was decreased by a more significant percentage than the baseload overnight and on weekends.

5 What is the most energy-efficient occupancy level as a percentage of max occupancy provided (i.e., occupancy on 2/10/20)?

The most energy-efficient occupancy level was 5% or an occupancy around 90-100 compared to the initial 1900.

To measure energy efficiency while controlling for factors such as the time of the year and the weather, we:

- Train a machine learning model on all data prior to covid

- Make predictions during covid without using the occupancy data.

- The model predicts consumption of each tenant meter as if the building were operating at baseline occupancy

- Compare the forecasted consumption at full occupancy to the actual consumption to determine the most efficient operation

- Results are controlled for external factors.

Although 5% was not the lowest overall occupancy, this level resulted in the most efficient operation. Above this occupancy, it appears the building was running more equipment to meet tenants’ comfort requirements.

6 What else, if anything, can be concluded from your model?

- Even a few tenants in the building drastically increases consumption

- There is a need for communication between building engineers running the building and tenants

-

If building engineers know the occupied floors and when tenants are present, they may be able to increase efficiency by selectively shutting off equipment

- The energy efficiency was highest during the late afternoon/evening because the building consumption began decreasing much earlier than before covid

- This observation indicates that perhaps tenants were leaving earlier during covid, or the building engineers realized they did not need to run the equipment as late to ensure comfortable temperatures

-

If the equipment could be shut down earlier in the evening, perhaps it could also be turned on later in the morning, saving additional energy

- Moreover, the energy reduction is greater during the day than overnight and on the weekends, indicating there may be an opportunity to lower the baseload even further during off-hours

- However, reducing the baseload might require more time for the building to reach temperatures in the morning, which could increase consumption

- There is likely an optimal tradeoff here that could be discovered through additional analysis

7 What other information, if any, would you need to better your model?

- Valuable additional data would be the occupancy per floor at each hour of the day.

- While this may be difficult to acquire due to privacy concerns, it would be beneficial for both predicting tenant consumption and for lowering overall energy use.

- If we could figure out the unoccupied floors based on patterns in the data (or by direct communication with the tenant), we could tell the building engineers not to operate the equipment for floors with no tenants.

- Another useful piece of information would be the lease obligations: the time at which the building must be within a comfortable temperature range.

- The lease obligations would help identify when the building should be starting up and could be combined with internal floor temperatures to determine if floors are conditioned too early.

- Were the floor reaching temperature too early, this would be an opportunity to save energy by starting the building’s equipment later.

- Any internal time-series data from the Building Management System (BMS) could improve this model or be used to construct other models for accurately forecasting consumption and identifying efficient operation

- Data involving the building’s indoor air quality:

- Fresh air percentage

- Air changes per hour

- Indoor carbon dioxide

- Indoor particular matter

- Optimizing the health indicators would create a better working environment for tenants, encouraging office reoccupation.

-

Buildings face the dual challenge of creating a healthy indoor environment and reducing their carbon footprint, but with the right information and a way to apply it, these two objectives can be jointly achieved.

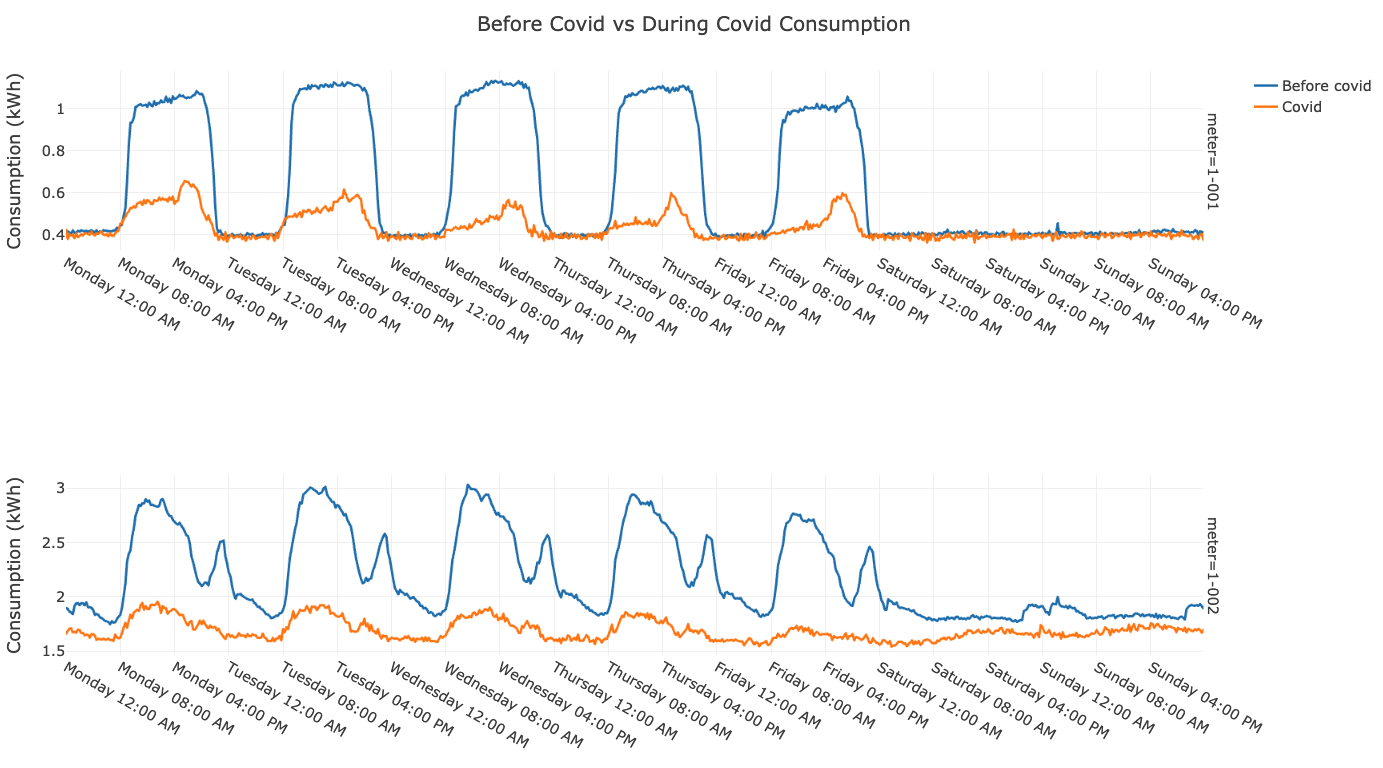

- Plot of before covid to during covid over a week