The Reality Of Global Nuclear Weapons And How Russian Nukes Turned On Your Lights

India’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (not a nuclear weapon!) launches in 2018 (Source)

India’s Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (not a nuclear weapon!) launches in 2018 (Source)

Exploring the data on the decline in worldwide nuclear stockpiles and the most intriguing government program you’ve never heard of: Reality Project Episode 3

On a warm Boston summer in 2018, I was just settling onto the lawn at the Hatch Memorial Shell for a performance of my favorite symphony — Holst’s The Planets — when I saw a tent set up by the Union of Concerned Scientists. As someone generally concerned about the state of science, I wandered over and as I got closer, was drawn to a crowd gathered around a man discussing the threat of nuclear weapons. Having just finished Enlightenment Now by Steven Pinker, I was hoping to hear more positive news about the massive reductions in nuclear weapon stockpiles that occurred over the past 30 years.

Instead, the man’s speech — as Pinker tells us to expect from academics — was entirely negative. The gist was that human folly led us to create weapons which could wipe our species off the face of the Earth and we were in grave danger. Perplexed, when the man paused to take a breathe, I raised my hand and asked if he knew how many nukes there were worldwide and how this compared to numbers in the past. Confidently he replied: “There’s more now than ever before although I don’t know the exact number.”

At this point, buoyed by the confidence (and arrogance) that comes with possessing data someone else doesn’t, I pressed my factual advantage for all its worth stating: “In 1985, there were approximately 70,000 nuclear weapons in the world, and today, in 2018, there are less than 15,000. That represents a reduction of nearly 80%, and what’s more, there are 4 fewer countries with nuclear weapons today.” Surprised, the man asked for a fact check, and after an acceptable source was consulted, he acknowledged the optimistic numbers were correct. While my intention was not to defang the man, this was the unintended effect, and the crowd slowly began to disperse, the gusto gone from the man’s proclamations.

Although I had inadvertently cost the man his entire audience, he agreed to have a discussion with me (after I apologized for the intellectual ambush) and we had a fruitful debate with both of us making concessions: I agreed that 0 nuclear weapons was optimal (although not realistic at the moment) and he said he would reframe his message to emphasize the progress we’ve made in nuclear weapons reduction. Later, as I sat listening to the sounds of Holst’s magnificent work, I thought about what this experience had taught me:

- Even experts are seriously wrong in their view of the world.

- People assume the worst of humanity in the absence of data.

- Don’t act superior to someone when you are correcting them. Remember that you were ignorant as well before you read the statistics.

In this article, we are going to examine the data concerning nuclear weapons around the world. The basic stats above are correct — the number of nuclear weapons and the number of countries holding them have both declined drastically in the past 30 years. However, there are also points about which we should rightly worry, including tension between the US and Russia which threatens arms control treaties and the possession of nuclear weapons by unstable states. In addition to the numbers, we’ll also learn about Megatons to Megawatts, the most intriguing government program you’ve probably never heard of, in which Russian bombs literally turned on your lights.

This article is the third episode of The Reality Project, an effort aimed at becoming less wrong about the world with data. You can find the previous article here and all of the articles by searching for the Reality Project tag.

The Facts

Our data in this article will come from Our World in Data: Nuclear Weapons, Federation of American Scientists: Status of World Nuclear Forces, and The Better Angels of Our Nature by Steven Pinker (who cites Scott Sagan). We will also talk about nuclear arms treaties with information from the Arms Control Association and the State Department . Information on the Megatons to Megawatts program is from the Arms Control Association.

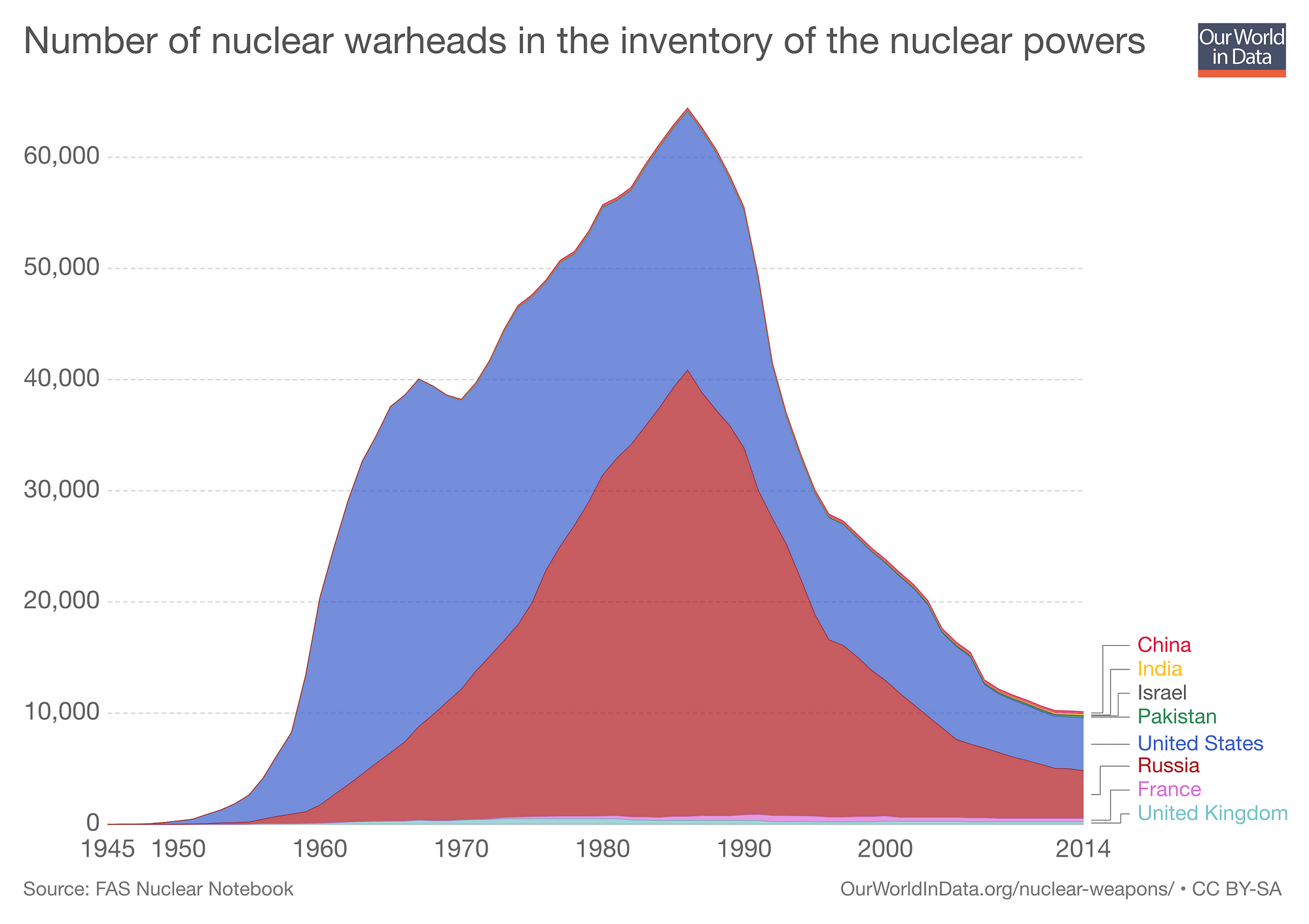

Exact data on the size of nuclear weapon arsenals is a closely held secret, nonetheless, we can get fairly reliable estimates due to international agreements and monitoring programs. From the objective data, we clearly see a decreasing trend in the number of nuclear weapons worldwide. Here is the global total of nuclear weapons over time (from Our World in Data):

Total number of nuclear weapons (deployed, stockpiled, and retired) over time.

Total number of nuclear weapons (deployed, stockpiled, and retired) over time.

The global nuclear stockpile peaked in 1985 and has been on a rapid decline ever since. Again, exact estimates differ, but the Federation of American Scientists states numbers went from 70,300 to 14,485 as of 2018. This respresents nearly an 80% decline in total nuclear weapons!

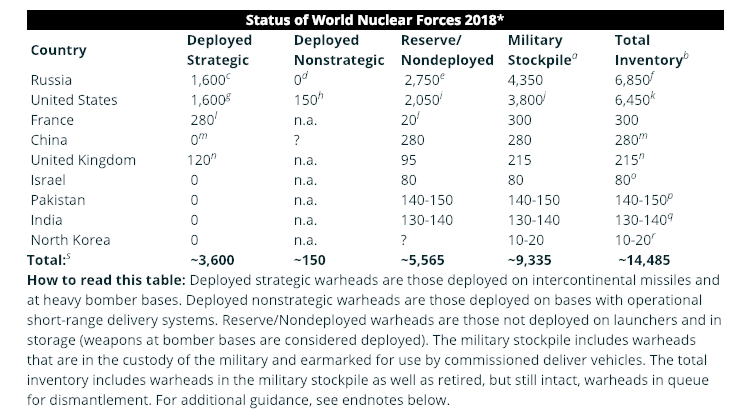

Today, there are 9 countries with confirmed nuclear weapons (it is unlikely there are additional countries with weapons due to the technology/material needs and international monitoring):

Countries with nuclear weapons and total numbers in 2018

Countries with nuclear weapons and total numbers in 2018

Russia currently has more overall nuclear weapons, while the United States has more deployed weapons_._ The state and type of nuclear weapons are just as important as the sheer numbers:

- Deployed: on ICBMs or heavy bombers, can be launched instantaneously

- Stockpiled: in storage with the military and “earmarked for use by commissioned delivered vehicles” (may be deployed)

- Decommissioned: retired from service and awaiting dismantlement.

- Strategic Weapons: larger weapons — such as ICBMs — which can be launched at a country from 1000s of miles away or on a bomber

- Non-Strategic (Tactical) Weapons: smaller yield, designed to be used on a battlefield, potentially in the vicinity of friendlies

The total in military use (deployed + stockpiled) is just under 10,000 with about 1,800 weapons on high alert. For all types of nuclear weapons, the worldwide total has declined substantially. For example, in 1986, Russia along had 40,000 nukes and now has under 7,000. The United States went from 31,000 in 1966 to under 7,000 in 2018.

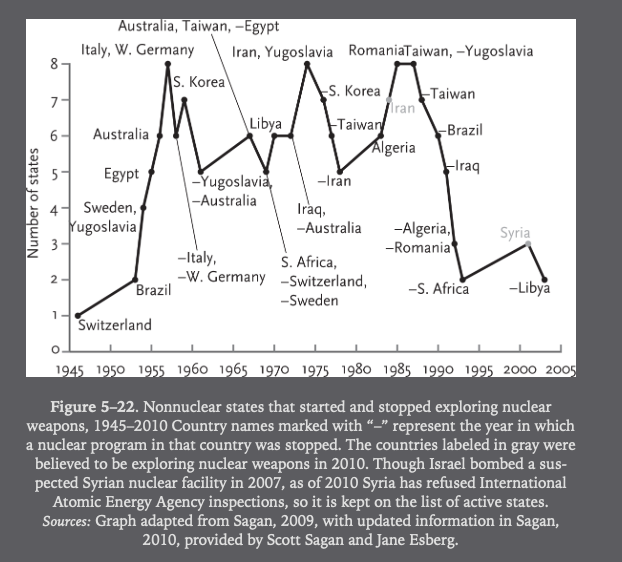

Another surprising piece of news is there are now fewer countries with nuclear weapons. 4 countries once had nuclear weapons but no longer do: South Africa, Belarus, Kazakhstan (which had 1,400), and Ukraine, which willingly gave up 5,000 nuclear weapons, the third-largest arsenal in the world. Moreover, many countries that were pursuing nuclear weapons at one point have since given up their nuclear weapon development.

In the below chart, we see when nations started and gave up trying to develop nuclear weapons (preceded with a — ).

Countries that started and then stopped nuclear weapon development (from Pinker with data from Sagan).

Countries that started and then stopped nuclear weapon development (from Pinker with data from Sagan).

Not only are countries with existing nuclear weapons working to reduce the number they have, but numerous other countries have decided that pursuing nuclear weapons is not something they want to do. In 1990, there were 13 countries in the world with nuclear weapons, a number that has dropped to 9 countries today. This is certainly positive, but three of the countries with nuclear weapons are concerning. India and Pakistan have fought 3 wars against one another, and North Korea is a complete unknown.

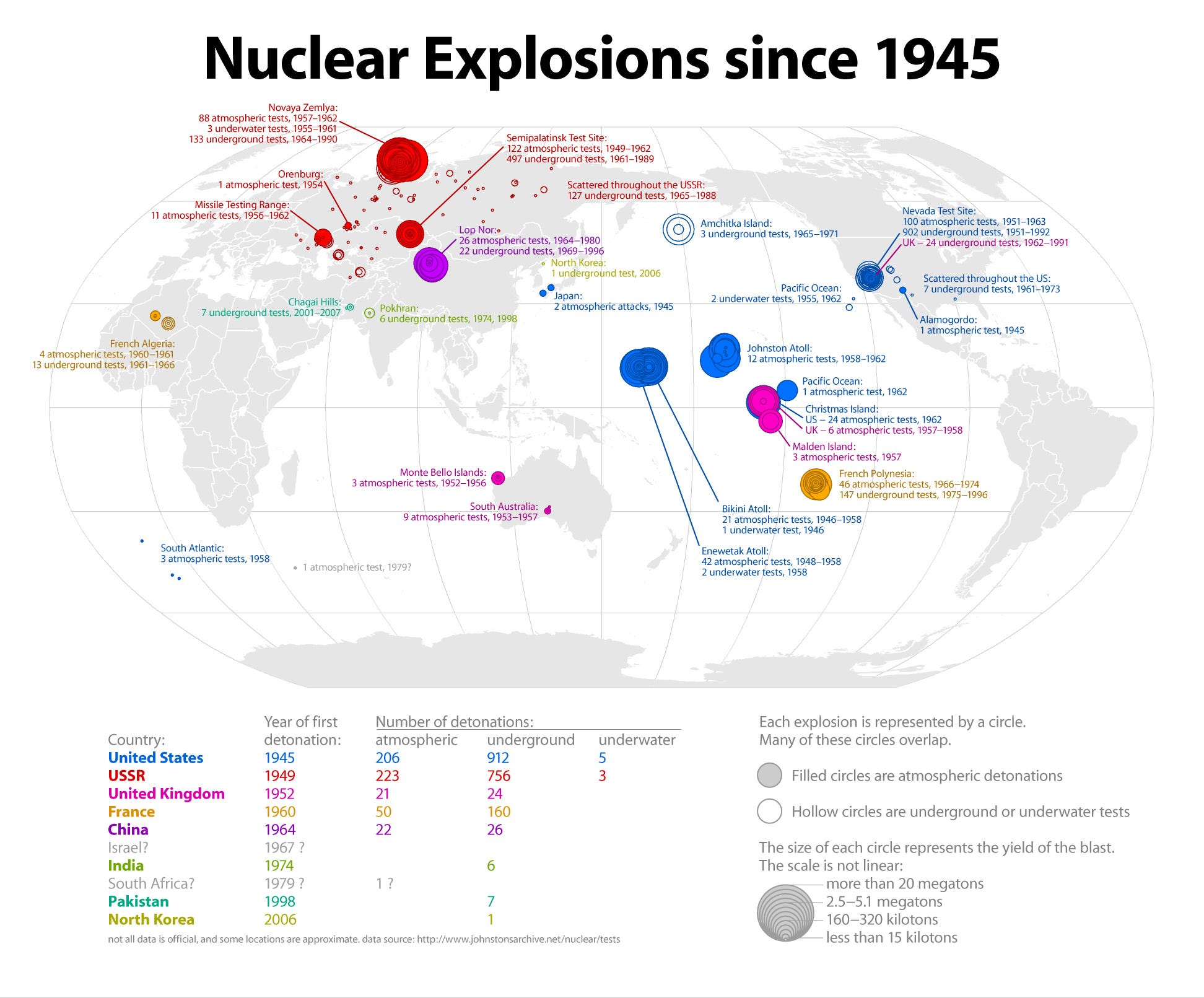

The decline in nuclear tests has been even more impressive than that of weapons. Since the start of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban-Treaty (which has not entered into force but is followed by the major world powers) in 1996, the US and Russian have not conducted a single test. Moreover, since 1999, only one country, North Korea, has done any nuclear testing at all.

Nuclear Weapons Testing (from Wikipedia which cites this SIPRI document)

Nuclear Weapons Testing (from Wikipedia which cites this SIPRI document)

The cumulative world total of nuclear tests is over 2000, but only 6 (0.3%) occurred after 2000. We can see where these tests happened in this map:

Map of Global Nuclear Tests and Explosions (from Radical Cartography)

Map of Global Nuclear Tests and Explosions (from Radical Cartography)

In summary, today there are around 15,000 nuclear weapons in the world (9,300 of which are in military use) held by 9 nations. 4 nations have given up their weapons while at least a dozen others have ceased development. The number of nuclear tests has declined to nearly 0 with only North Korea conducting any since 1999. Finally, projections for 2020 suggest there will be around 8,000 total nuclear weapons in the world.

How Did We Get Here? Arms Reduction Treaties

The decline in the size of global nuclear arsenals is undoubtedly a positive and as with any statistic, it’s helpful to understand why this happened so we can figure out if it will hold and what we can do to keep the trend on track.

In short, the reduction in nuclear weapons has come about because of international treaties designed to reduce arsenals. We don’t have the space to address all of them (see here for a comprehensive list) but we’ll talk about several between the US and Russia. Together, these two countries control over 90% of nuclear weapons, so these agreements have a significant influence.

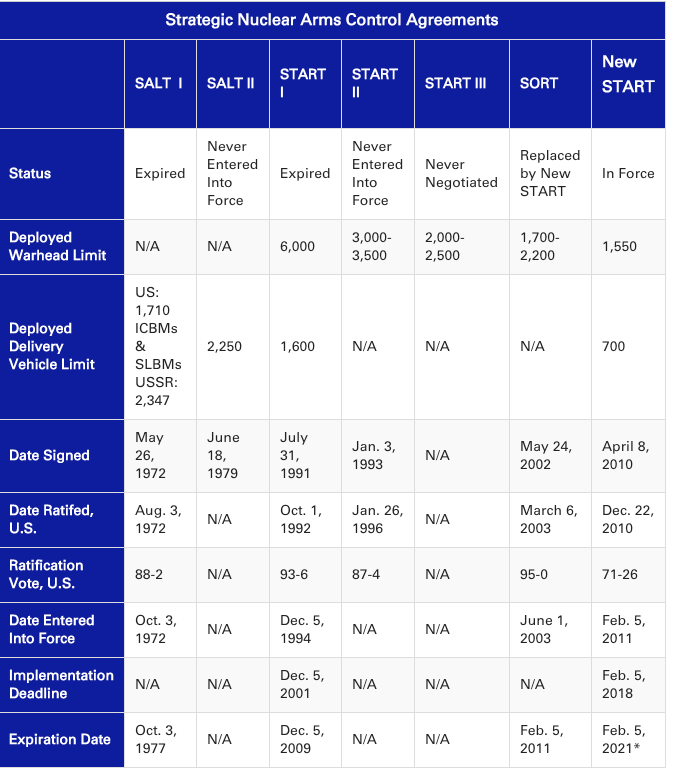

An overview of nuclear reduction treaties between the US and Russia is here:

Overview of nuclear agreements between US and USSR/Russia (Source)

Overview of nuclear agreements between US and USSR/Russia (Source)

From the table, we can see that not every negotiation was successful. Nonetheless, the treaties that have been agreed to have been effective. For instance, START I (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty), proposed by Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, (it was delayed by the collapse of the USSR) achieved all objectives, with Russia and the US reducing weapons to 6,000 each by 2001.

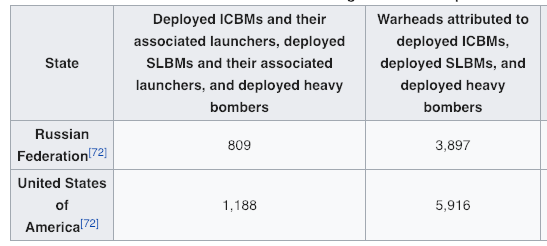

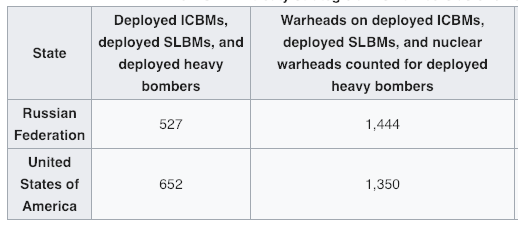

START I expired in 2009, but by that point, the SORT (Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty) agreement was in place which further limited both US and Russian stockpiles. As a note of optimism, this treaty was passed in the Senate by a vote of 95–0 indicating that both parties can at least agree we don’t need the threat of annihilation hanging over our heads like a Sword of Damacles. The current treaty limiting nuclear weapons, New START, was ratified in 2010 with reductions completed by 2018. We can examine effect of this treaty by comparing the number of warheads before (left) and after (right) completion:

Number of nuclear weapons in Russia and US before New START (left) and after (right).

Number of nuclear weapons in Russia and US before New START (left) and after (right).

Based on the final numbers (far right column), but the US and Russia have fewer deployed warheads than required by the Treaty (1,550)! The New Start Treaty officially expires in 2021, with options to extend it for 5 more years. The current President of the United States has voiced disdain for New Start, but there are no indications that the treaty will end early. (For a discussion of current developments, refer to this page from the arms control association.) With the present political climate, it is unclear what future arms control reduction measures will be put in place. Given the success of previous efforts, further arms reduction treaties must be a priority for both the US and Russia.

Verification of these treaties involves on-site inspections, exchanges of information, remote monitoring, and surveillance including satellites. To prove the US had followed START I, 365 B-52 bombers were flown to Arizona, stripped of usable parts, and then chopped into pieces. They were left out for 3 months to allow Russian satellites to confirm the destruction.

Destroyed B-52s as part of START I (source)

Destroyed B-52s as part of START I (source)

Other reductions of nuclear war threats have come without a bilateral agreement, including in 1991 when George H.W. Bush announced the US would remove almost all US nonstrategic (these are also called tactical nuclear weapons and are designed to be used on a battlefield) nuclear arms from deployment as the Soviet Union dissolved. As planned, the Soviet Union responded in kind, with Mikhail Gorbachev promising to withdraw all tactical Soviet nuclear weapons from naval deployment. This act alone, officially known as the Presidential Nuclear Initiatives (PNI) reduced the total number of nuclear weapons in the world by about 18,000. Although Russian and the US still possess both strategic and non-strategic nuclear weapons, the totals are at all-time lows (for a discussion of whether this will hold, see here).

Megatons to Megawatts: The Coolest Government Program You’ve Never Heard Of

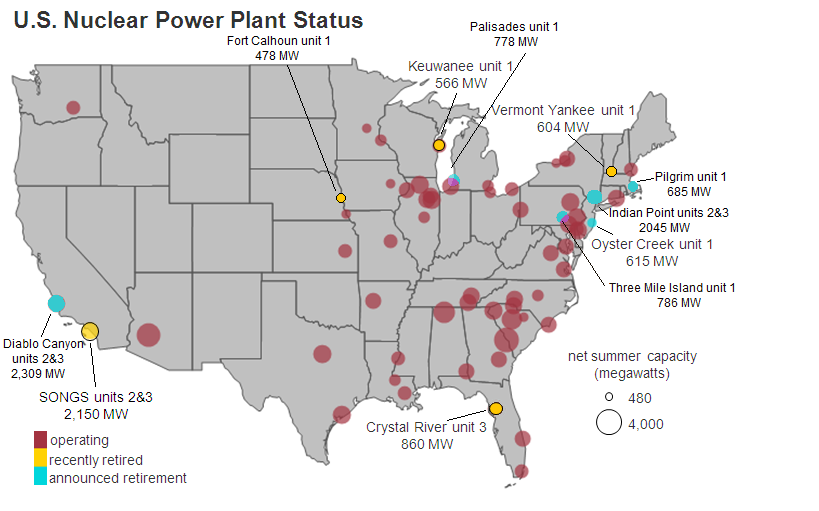

Sometimes, especially when the fate of the world hangs in the balance, the government can do some amazing things. One lesser-known case is the “Megatons to Megawatts” program in which 500 tons of highly enriched uranium (HEU) from Russian nuclear weapons was converted into low-enriched uranium (LEU) and sold to United States companies to be used as fuel in nuclear power plants.

The total impact of this astonishing program was that 500 metric tons of HEU — enough for 20,000 nuclear warheads — was converted into 14,000 tons of LEU and used to power nuclear reactors around the United States. (The cost of this 20-year program to taxpayers was $0 because the $12 billion of uranium was bought by the United States Enrichment Corporation.)

Over the 18 years of the program (1995–2013), the LEU fuel provided about 50% of all uranium consumed by US nuclear reactors, meaning almost 10% of electricity generated in the United States was from old Russian nuclear weapons! If you get any of your power from a nuclear station, then your lights were literally turned on by Russian nuclear weapons:

Nuclear power plants in the United States (Source)

Nuclear power plants in the United States (Source)

The total benefits of Megatons to Megawatts were enormous to both countries. The United States needed fuel for its nuclear reactors, and Russia needed cash after the fall of the Soviet Union. Both parties got exactly what they needed with the program successfully ending in 2013. Since then, the US has voluntary converted some of its HEU to LEU so it cannot be used in weapons and an agreement was signed in 2008 allowing the Russian nuclear industry to supply up to 20% of the US demand for uranium products until 2020.

The importance of the Megatons to Megawatts program — in addition to material benefits — is it shows that countries can overcome their differences, particularly when it is in both parties economic interest to do so. It also proved that former enemies can work together and resolve disputes peacefully. As we think of how to resolve situations in our personal lives and on an international scale, we’d be wise to keep this program in mind: compromise means that both sides don’t get everything they want, but everyone eventually benefits.

Conclusions

Nuclear weapons are not going away for the foreseeable future. While in a perfect world there would be 0 nukes, we live in reality, not in a utopia. Therefore, as a short-term realist and long-term optimist, I appreciate the significant progress we have made — massive reductions in the number of nuclear weapons — while acknowledging the need for continued reductions.

Furthermore, while I am glad there are concerned scientists, I would like them more if they had their facts straight before they speak from a position of prominence. Telling people the world is worse than it is will not lead to action, but to disillusionment and the belief that things can never get better. It’s worth remembering that progress is never directly linear, but has been trending positively for most of human history and has sped up in the past several decades. As nuclear weapons demonstrate, things could be both much worse and much better, and international efforts do work on a global scale.

As always, I welcome feedback and constructive criticism. I can be reached on Twitter @koehrsen_will.