100 Miles Through The Park What Its Like To Run A 100 Mile Ultramarathon

The Why and How of Running an Ultramarathon: A Personal Account of the 2019 Potawatomi Trail Runs

Why? Before you can even talk about running a 100-mile ultramarathon, you have to answer the inevitable question: why put yourself through months of training, make numerous sacrifices, and endure extreme suffering, all to spend 24+ hours running around a park in the middle of nowhere? Throughout history people have given good reasons for doing difficult things: Mallory’s “because it’s there” and Kennedy’s “because it’s harrrrrrrd” come to mind. For myself, I’ve found ultra-athlete David Goggins’ reasoning to be more on point. Put simply, I am terrified of living a life so unchallenging that I never figure out what I’m capable of.

Call it a quarter-life crisis. At the age of 22, with no debt, a dream job, and a fledgling retirement savings account, I had reached a new stage in life, one many people would call “comfortable”. However, instead of being satisfied, I was scared. I woke up one morning and realized if I wanted, I could spend the next 40 years living the “American Dream”: work 8 hours a day and come home to indulge in a buffet of mind-numbing drugs: television, social media, or increasingly for my generation, video games. Weekends would require no more effort than that needed to get up and ingest 3 meals a day. In short, I was staring at a life of ease.

While some may consider a comfortable existence to be a personal apotheosis, for someone who had spent his entire life striving towards one goal after another, the prospect of an easy life freaked me out. I needed a challenge to force me outside my comfort zone and focus my efforts. Having just come through the mentally torturous (in more ways than strictly academic) college experience, and with a relatively stimulating job, I opted for something physical, a trial I knew was beyond my current capabilities. Hence, at the end of January, I signed up for the 100-mile ultramarathon at the 2019 Potawatomi Trail Runs, on April 4–7.

It wasn’t so much the physical act itself that enticed me (although I do feel more alive when I’m running than at any other time) as much as it was the difficulty. A good challenge can be mental — teaching myself data science in 9 months on my own — or physical. The important point when choosing something to pursue is that the task must require prolonged training over months/years and it must lie outside your abilities. I’d run 5 ultramarathons in the past (although none longer than 66 miles) and knew what it involved: months of training with days consisting of a 5 am morning run, work, an evening run, and then bed by 9 pm. This effort would culminate in 24+ hours of continuous running on the trails of hilly McNaughton Park. Yet, when I signed up, I wasn’t thinking about all the suffering. Instead I relished the opportunity to test myself. Everyone is capable of a lot more than they think, yet the vast majority never find this out because they refuse to get out of their comfort zones. Either I would discover I wasn’t tough enough to run 100 miles or I would surpass my perceived limits.

The Race Setup

With the hardest question out of the way, it’s time to get down to details. This isn’t an article detailing my training because I want to focus on the event itself. Needless to say, my training involved some running: about 120 miles per week for 8 weeks, with every single mile on the flat roads of Brooklyn/Manhattan. I didn’t want the running to affect my work or how much time I could spend at work, so I did what seemed most obvious: I forbid myself from riding the subway and ran back and forth (6–8 miles depending on the route) to work every single day. Even with all that running, I was worried about preparation because 100 miles on the trail at McNaughton Park was going to be a little different than running the streets of Manhattan.

A small uphill on the course.

A small uphill on the course.

There are two different types of ultramarathons:

- Timed: Run for 3/6/9/12/24/48+ hours with no set distance on a track, a city street, or a mountain trail. The only finish line is your own mind or the time limit, whichever comes first.

- Distance: starting at 50k (31 miles) and going up to 3100 miles (a race run for 60 days in New York City) run for a pre-defined distance (usually also with a time limit so the race organizers can eventually go home)

The Potawatomi Trail Runs are of the latter variety with distances from 10 miles to 200 miles. Ultramarathon courses vary significantly from quarter-mile tracks (yes there are races where people run for 48 hours on a track) to trails circling mountains. The Potawatomi Runs are held at McNaughton Park in Pekin, Illinois on a 10-mile loop of mostly single-track (a trail wide enough for one person) and also some double track through open fields.

Typical trail.

Typical trail.

A single lap at McNaughton has 1600 feet of elevation gain and 1600 feet of elevation loss. For reference, from base camp of Everest to the highest summit in the world is 12,000 feet of elevation gain, meaning that over 10 loops, not only would we cover 100 miles, we would also gain more vertical distance than climbers do when ascending Everest from base camp. Mother Nature blessed us with heavy rain the day before the 100-mile started, turning hard-packed trails into 6 inches of slippery mud. As if that weren’t enough, the course featured 2 creek crossings with a depth of about 2 feet and a field with standing water (nicknamed “the field of wet dreams”). In short, not only would we have to run 100 miles through sucking mud while climbing 16,000 feet, but we would also have to do it with perpetually wet feet.

Beautiful mud and water on the course.

Beautiful mud and water on the course.

Making any ultramarathon course more hospitable are the aid stations: wonderful oases of food, drinks, drugs (acetaminophen and caffeine), and human companionship. There were three on the McNaughton course, at 3 miles, 6 miles, and the start/finish. These aid stations were crewed 24/7 by an incredible bunch of volunteers who dedicated their weekend not to running 100 miles, but to helping other people run 100 miles. The aid stations are a great reminder that even though running is an individual sport, no one completes a race by themselves. Behind every runner is an army of family, volunteers, and support staff who make it all possible. No matter what you do, there is a community of like-minded people dedicated to that pursuit. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve increasingly realized the importance of community (what Robert Putnam calls social capital) and I’m proud to include ultra-runner on the communities to which I belong.

The main aid station, featuring food, drink, and a wedding proposal!

The main aid station, featuring food, drink, and a wedding proposal!

McNaughton Park is not the toughest location for an ultramarathon (how about Death Valley or Mount Blanc in Switzerland) but it does present a challenging variety of terrain. I had tried to compensate for the lack of elevation gain in NYC by getting in as many miles as possible and spending roughly 30 hours a week exercising. Nonetheless, nothing can prepare you for the course except actually running on it. A week before the race I flew home (the course was 30 minutes from my parent’s house) and ran it twice beforehand with my brother who was also running the 100 miles. It looked exactly as promised: pretty gnarly, which I embraced. If it was easy, there’d be no point in doing it.

** * **

** * **

Kicking Things Off

In high school, I ran hundreds of 5 km for the cross-country team and, without exception, the start was always the worst part of a race. (As a side note, I went straight from 5km to 50km after high school, which significantly improved my love/hate relationship with running.) After static/dynamic stretching, warm-up runs, and a team prayer during which the tension slowly built up, we would head to the starting line and cram into a starting box for 5 minutes of pure anxiety. The nervous butterflies would get worse and worse as you contemplated the pain to come over the next 20 minutes, until, finally, the starting gun would release you from the torture.

In contrast, the start of an ultramarathon is a decidedly pleasant experience. Since you’ll be running for 24+ hours, no one is that eager to get started and, because the pain of an ultramarathon is of much lower intensity than a 5 km, there are few nerves. At 5:30 am on April 6, hundreds of runners milled around near the Potawatomi start line, drinking coffee, scarfing their choice of fuel (from peanut butter sandwiches to quesadillas to chicken noodle soup) and talking about everything except the race. I like to say that ultramarathons — at least those with no money on the line — are akin to a long party with a little running thrown in. You talk with friends, eat and drink a ton, listen to some music, and oh by the way, happen to run 100 miles. Nowhere is this low-key atmosphere captured better than at the start.

Just hanging out waiting to run 100 miles.

Just hanging out waiting to run 100 miles.

At around 6 am — the scheduled start time — the race directory says “you’re free to go now” and go we do — not at a sprint or even a run, but a general shuffle in the direction of the start line. A good rule of ultrarunning is to start slow and get slower, and thankfully, the number of people combined with the narrowness of the trail enforced that at Potawatomi. If you had wanted, you probably could have gotten out ahead of everyone and taken off, but it’s much better to follow the lead of the wiser, older runner and just go with the crowd.

My brother and I started the race out at the same pace as everyone else — a nice slow shuffle. I like to stress that ultramarathons are “runs” as opposed to “races” because the point isn’t to compete with others, it’s to challenge yourself, engaging in a personal battle between you and the course. There’s no reason to push towards the front or take the lead; instead, just enjoy the experience! With 24+ hours of suffering ahead, there’s no reason to spend unnecessary effort on a quick start.

As an interesting aside, ultrarunners do not fulfill any runner stereotypes: you’ll see every body shape, size, and age represented, especially at the lower-key events. If I had to guess, the median age at Potawatomi was probably 45, and you’d never be able to pick any of the ultramarathoners out of a crowd of regular Americans (okay, a crowd of any other reasonably athletic Americans). It’s always been fascinating to me that so many different body types can be successful ultramarathon runners, and I think it speaks to the fact that so much of running long distances is mental. Finishing a 100-mile race is much more about whether you have the mental fortitude to keep preserving when the going gets tough rather than if you have <5% body fat (which might actually be a detriment over longer distances).

Additionally, at the start, we watched as the 200- and 150-mile runners ambled by. Because of the longer distance, they had begun on Thursday and were 36 hours into their races enduring heavy mid-race rain showers along the way. Many had already covered 100 miles with 100 more miles still to go. Observing these grizzled runners (of all body types) was a great reminder that no matter how tough you think you are (“I’m a bad-ass because I can run 100 miles”) there is always someone tougher or better than you. Stay Humble.

Starting a 100-mile race.

Starting a 100-mile race.

Loop One: Working out the Kinks

There is something magical about running in the morning as the sun comes up hours before most people even think about getting out of bed. It’s as if you are getting a head start on the world, making an investment that will pay off throughout the day. I’ve always enjoyed running in the morning, and this run was no exception. As the sun made a full appearance and we gradually turned off our headlights, I concentrated on assessing the course. Although my brother and I had already seen the course twice, the rains of the previous day — and thousands of cumulative footsteps — had transformed the ground, with wide ruts and vast expanses of mud covering the course. Seeing the state of the course, I started wondering if my tiered pre-race goals were too ambitious.

Speaking of goals: the problem with setting a single objective is it divides the world into strict black and white: you either succeed or you fail with no middle ground. This leads you to lose all motivation if you don’t meet your goals or set low objectives so you are guaranteed to hit them. In reality, life is all shades of gray, with success not as easily measured as yes or no. Therefore, for any race — or major life project — I set up a tier of goals: A, B, and C. An “A” goal should always be audacious with B and C goals scaled back to offer more realistic ambitions. Sitting in my NYC office when I signed up for the race, my goals were 20 hours, 24 hours, and finishing. Having run the course pre-race, I revised those goals to 24 hours, 30 hours, and finishing. Now that I was on the course, I was having doubts about even these tiered objectives, but I tried to put any thoughts about the entirety of the race out of my mind.

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned from running is once you have started the race, you need to stop thinking about the whole event. With such a large task, it’s impossible to take on all at once. Instead, you have to subdivide the race into manageable chunks. No one runs a 100-mile race all at once, you run it one lap at a time. Sometimes even that’s too much, so break it down into smaller chunks: aim to get from one aid station to the next. At the extreme limit, when you are broken and can’t imagine going on, take it one step at a time. You can always take at least one more step, and when you do, you’ve made a little forward progress. After enough time, you’ll realize you made it further than you ever thought was possible. Far from being limited to running, this mindset works for any large task, from teaching yourself a new language, to making it through graduate school. Goals are important to orient yourself, but once you have overall goals, break them down into chunks you can actually get done, one piece at a time.

Keeping that idea in mind, I told myself to dispel all thoughts about “running 100 miles” from my head and use the first loop to get accustomed to both my physical and mental strategy. On the physical side, I was most worried about proper fueling because of past experiences and because it’s hard to train for eating and drinking over 24 hours of running (my longest training run clocked in at 26 miles in 4 hours). At the least, I wanted to be drinking and eating at every single aid station which meant about every 3 miles.

The second aid station.

The second aid station.

On the food side, I try to stick to “real” nutrition, which for me means solely peanut butter sandwiches if possible (if not, then mashed potatoes tend to hit the spot). Fortunately, all three aid stations had peanut butter sandwiches in abundance. Hydration for many ultrarunners includes a mix of water, soda, and Gatorade. You will often see runners drinking Coke/Mountain Dew/ Pepsi in the midst of 100-mile races because of the simple equation: sugar = calories = fuel = miles. For me, I’ve always found soda and Gatorade (which is just soda without the carbonation) to be too sweet and I usually rely solely on water for training. However, during a race, water lacks the crucial calories your body needs to keep going so I made sure to hydrate with Tailwind, a lower-sugar, higher-electrolyte version of Gatorade.

One of my greatest pre-race sacrifices had been cutting caffeine intake from 2 cups of coffee to 1 and eventually none so it would have the “maximum impact.” This may have been complete pseudo-scientific bs, but it seemed to work. I drank 1 cup every 2 laps (20 miles or about every 5 hours) and each cup was like a nitrous oxide shot in an internal combustion engine (note to my non-existent editor: I have no idea if this is a good metaphor).

The problem with figuring out nutrition for an ultramarathon is that each individual is unique and there are no universal best practices that apply to everyone. With a limited sample size (again, it’s hard to recreate race conditions in training) each race is essentially an experiment. I like to eat the same thing over and over again and have found a food (pb sandwiches) that works perfectly for me. On the other hand, my brother, said he tired of the same food and had to mix it up to force himself to get the calories he needed. To each runner her own nutrition strategy.

Equally important — if not more so — than your physical strategy is how you approach the race mentally. At the end of the day, what determines whether you finish or give up is not the physical condition of your body, but your mental fortitude. In fact, I see the point of training beyond a certain point (70 miles a week seems like a minimum for running a 100-mile race) not as preparation for the body but as preparation for the mind. You have to strengthen your head to keep your body going even when it wants to stop. The human body will start sending out pain signals way before you actually are nearing your limits, and learning how to ignore these is where most of the benefit of prolonged training occurs.

By the time of the race, it’s too late to do any more mental training (the hay is in the barn so to speak) but my race-day mental strategy was simple: there is only one loop to run, and it’s the one you are on. Just as you can’t write Chapter 10 of a book until you’ve written the first chapter, you can’t run lap 10 of a 10-lap 100-mile-race until you’ve run the first, second, etc. This might seem stupidly simple, but it’s surprising how many people convince themselves they have to stop when they are on the second loop because they can’t possibly run 80 more miles. My response is that you don’t have to run 80 more miles, you only have to run 10, the current loop. If that doesn’t work, then tell yourself you only have to run 3 miles — to the next aid station. Keep reducing the distance until you’ve reached a manageable chunk and then complete that chunk. Keeping knocking off pieces until you’ve run 100 miles — nothing more to it.

Creek crossing: wet feet are just one of the joys of running!

Creek crossing: wet feet are just one of the joys of running!

Loops 2 and 3: Settling in for the Long Haul

While I was trying to figure out the course and put my physical and mental strategies into place, the miles rolled by and just like that the first loop was done, and shortly afterward the second and third. I struggle when people ask me what I think about when I run — it varies, and often I can only describe it as thinking of nothing after the fact even though I know for sure I had to be thinking of something while running. When I run in NYC, I listen to Audiobooks — everything from Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning to Michelle Obama’s Becoming. I’ve found running in the city over the same streets can get boring and audiobooks give me something to focus on and also quiet the voices in my head telling me to stop.

For this run, I had the usual interesting mix of audiobooks all queued up: Can’t Hurt Me by David Goggins, The Fifth Risk by Michael Lewis, The Spy and the Traitor by Ben Macintyre (if you are looking for a pattern in what I read, spoiler alert, there is none.) However, for this race, I soon realized I wouldn’t be needing anything to keep my mind busy. Just the act of concentrating on the trail — with roots, creeks, rocks, mud, trees, and other runners to watch out for — and trying to strategize my pace, nutrition, and bowel movements (yes, this is a significant challenge) kept my mind occupied. I ended up running the entire race with no audio playing in my head except a constant internal monologue: “There is only one loop. At the next aid station eat two peanut butter sandwiches. There is another runner, let’s catch up to her and keep pace for a few miles. There is only one loop. How is your nutrition going? When was the last time you urinated and what color was your urine? There is only one loop.” Over and over for 100 miles and 27 hours.

Was the race boring? No. In fact, besides when I’m in the zone at work, I never feel more engaged than when I am trail running. Moreover, running an ultramarathon is one big exercise in management: what to eat, when to eat, when to rest, when to pick up the pace, when to walk, etc. Part of what drew me to ultramarathoning is the logistics aspect of it. You have to plan out your race and then execute on that plan, adjusting as the conditions change. With all the details to keep in mind, the miles fly by and I finished the first 3 loops in 7.5 hours, exactly on pace for a 24 hours finish.

Loop 4: The Depths of Despair

It’s true what they say about ultrarunning: when you are feeling bad, don’t worry, things will get better, but, when you are feeling good, you should worry because pretty soon you’ll be feeling bad. (A less cryptic way of putting this is that an ultramarathon is a roller-coaster of emotions). After 3 loops I was feeling about as good as I could expect, but then starting out on the 4th loop, I made a crucial mistake: I began thinking about the finish line. I had done the (impressive) math and realized even though I had already done over a marathon, I still had 70 miles to go, at this pace, at least another 16 hours. The constant doubts espoused by my mind, which I had been able to keep at bay by narrowing my focus, finally asserted themselves loud and clear.

Over and over I started thinking things like: “You’re wasting your time out here. You should just stop now instead of failing later.” On mile 35, with no one else around, ascending yet another hill, these thoughts were overpowering. Why keep up the struggle for what ultimately, was a meaningless pursuit? Perhaps the most insidious thoughts were not the negative ones, but the ones that tell you to take it easy: “you’ve already done a marathon, something most people never do. Why not call it a day?” It was at this point that I had my only real thoughts of quitting. I’m not sure why — there were certainly more difficult physical moments ahead — but this was the mental nadir of my race. I think it was precipitated by worrying about the end of the race, but it could have been caused by any number of factors: fatigue, lack of human contact, low blood sugar. Whatever the cause, I was in crises, and halfway between aid stations 1 and 2, I started walking sections where I normally would have been running, trying to just maintain forward progress.

As the thoughts of quitting continued their barrage, one stood out in particular: “No one will think less of you because you weren’t able to run 100 miles.” As I pondered that last thought, I realized it was false. It should be “no one else will think less of you.” However, the only person that mattered to me during the race — myself — would never be able to get over the shame of quitting. I saw an opening for reasserting my will to continue and started to pry it wide. (Side note: it’s not always shameful to quit. If you are injured and continuing on would result in permanent damage, then you need to stop. Knowing the difference between when your mind is trying to trick you into stopping and when you are actually hurt is extremely difficult).

I thought about all the training I’d done over the months and drew on the times I had not wanted to take another step but kept going anyway. Running after a 10-hour workday (I work long days because I enjoy my job. If you like what you are doing at work and have no other obligations, why leave?) is tough — but I had always made it out the door and gotten in my second run of the day. There were often times when I was too tired after work to change my clothes but I still needed to run, so I did an 8 mile run in khaki pants and a dress shirt (in case you don’t believe me, my co-workers can confirm. And, if you saw a skinny guy in business casual running over the Brooklyn Bridge in February or March, there’s good money it was me). It was those mental triumphs over the course of my training, a hardening of my mind, that ultimately kept me going in the depths of despair on lap 4.

To escape my doubts, I stopped thinking about the race as a whole and narrowed my focus, first to this one loop, then to the next aid station, and finally making it to the next landmark. If I could reach the next tree, then I could stop. Only, once I reached that tree, I saw no point in stopping so I went to the next tree. And so on until, eventually, I emerged from the forest another lap complete. In a time of crisis, I had done the only thing possible: relied on training, remembered the plan, narrowed my focus, and kept making forward progress. Having conquered the fourth loop, that was now another experience I could use going forward. During the rest of the race (and many times afterward in my daily life), I thought about how I had not stopped despite the want to give in and used that as fuel to continue on.

Making it to the finish of another lap.

Making it to the finish of another lap.

Loop 5: Those Left Behind

With my triumph in the psychological war of the fourth loop, things didn’t necessarily become “easy”, but, over the rest of the race, I was never again besieged with the same doubts. I found a groove and started hammering out the miles (by this I mean mostly walking and running when possible). I was still on pace for an under 24-hour finish and felt fine considering the circumstances. The 5th loop was shaping up to be pretty normal until a notable encounter right before one of the largest hills in the race.

Sitting on a log by the side of the trail, I spotted a man, clearly one of the 200-mile runners by the fatigue showing on his face, hunched over in a sign of defeat. Like every other runner ahead of me, I stopped and asked him if he needed help (the most important rule of ultrarunning is to look out for others.) After a long pause, he glanced in my direction and stated simply “wall”. That one word was enough to answer my question. No, this man was battling his own demons and didn’t need my or anyone else’s help.

In this case, the runner was struggling with one of the worst obstacles, the dreaded wall that occurs at any moment leaving you unable to take another step. It can be caused by physical pain or mental doubts, but it’s something every runner has struggled with. At times like these, there’s nothing outside help can do. It was up to this man to either press on or succumb. I nodded and started walking away to head up the hill. As a parting comment, the man once again said “wall” and hung his head. Later, I would see this man at the finish line, and note he had managed to finish the lap but not the full 200 miles.

I thought a lot about that man over the rest of the race. What causes some of us to keep going while others break down? Is it environmental? Something innate? Why do some people grow stronger when experiencing adversity and others wilt? What drives those who continue and what finally breaks the motivation of those who give in? Partly, I was running this race to answer those questions for myself. It’s easy to say “of course I would get past that wall” when you aren’t experiencing it, but nothing can recreate the feeling and actually test your determination other than getting out there and putting yourself in those situations. Fortunately, ultra-running repeatedly forces you into these character-testing moments. I thought my wall moment had come on loop 4, but there is no rule limiting you to only one per race and I worried about how I would respond again. To keep these thoughts out of my mind, I tried to stop thinking about those who would not finish and turned back to my strategies. I was heading into uncharted territory after 50 miles and was thankful for the mental effort required to work out the logistics.

Loop 6 and 7: Into the Darkness

The fifth loop ended at 6 pm, exactly 12 hours after I had started. This meant I was on track for a 24-hour finish, but I put all thoughts of the distant finish line out of my head. As the race director was kind enough to remind me, anything can happen on each step of the 10-mile loop, let alone over the next 50 miles. Before the sixth loop, I grabbed my headlight in preparation for the onset of darkness. I had run in the “dark” before, but only in the morning in New York City where it never truly gets dark. I was worried about all sorts of things. While training, I had never been up past 9 pm (another sacrifice you have to make) and never in my life had I even stayed up for more than 18 continuous hours. Now, I would be asked to not only extend that beyond 24 hours, but also have to run/walk the entire time.

The start/finish tent illuminated at night.

The start/finish tent illuminated at night.

Furthermore, 12 hours was the longest I had continuously run before (around a 1-mile gravel loop in Alabama) and I had no idea how my body would respond. Currently, it wasn’t giving me any problems (food/drink was going in and coming out again with no issues) but that means nothing in a race where a single wrong footstep could end your run. On top of all that, the forecast was calling for storms in a few hours. I thought about all these obstacles and replied with the only correct answer for a tough situation where the deck is stacked against you: “good”. This approach to life, which I picked up from former NAVY seal Jocko Willink is savage and simple: start listing every obstacle you face and to each one reply “good”. There’s nothing you can do about external challenges, so you might as well embrace them. Revel in the suffering. (The “good” technique comes from this podcast episode which is worth listening to in its entirety.)

With that one that one-word refrain echoing in my mind, I started out on loop 6, pushing past all previous personal boundaries. This loop would take about 3 hours (ending my hopes for a sub-24-hour run) and end in complete darkness at 9 pm. Despite my fears, I found running in darkness was not any more difficult than running during the day. It might require a little more effort to see where you are putting your feet, but the same idea applies, keep going forward. This minor realization reflects a larger point: our fears are always worse than reality.

Our brains tend to inflate problems (“making mountains out of molehills”), which, unfortunately, means we often don’t tackle tasks because we psyche ourselves out before we’ve even tried. If you don’t believe me, try asking your boss for a promotion right now. The frustrating part of this habit is the reality is never as bad as we imagined it was. However, if you can push past your anxieties a few times, then you can draw on that experience to do it repeatedly. The best way to stop fears from controlling your life? Be bold, keep going, and don’t stop to listen.

Loop 8: Otherworldly Experiences

For several years I haven’t been religious in the least, but that does not prevent me from occasionally having wonderful moments when I feel connected to something larger than myself. These moments occur when I’m listening to a great symphony, reading an incredibly moving tale of human perseverance, writing about something profound, or most commonly, exercising intensively for a prolonged period. In the middle of loop 8, at 1:30 am, after 19 hours of running, I had another one of these awe-inspiring moments.

After leaving the first aid station, I did not encounter another human being for over an hour. I might as well have been alone on the trail or alone in the entire universe as I made my way through the silent woods in a state of complete contentment. Finally, just when I thought maybe I was the only one left, I caught the first sounds of human activity. The great part about aid stations — particularly at night — is you can hear them long before you see them. The diesel generators (perhaps the only use of fossil fuels I wholeheartedly endorse) roaring away, the faint bars of music, and even occasionally that most pleasant of sounds — human voices — come drifting through the air and you know you are approaching an oasis with warmth, food, and company.

Around mile 76, as I continued to make slow progress through the trees, I caught the opening bars of Jimi Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower” rolling through the night air. The music pulled me along, growing louder and louder until, as the last notes drifted off, I ran into the station, lit up by a disco ball and stocked with the most heavenly of foods: coffee and peanut butter sandwiches. After a brief stop and some welcome conversation — people who man aid ultramarathon aid stations at 2:00 am on Sunday morning are angels — I headed out again into the darkness, for another hour by myself.

Aid Station Two (notice the disco ball hanging from the tree). An oasis in the woods

Aid Station Two (notice the disco ball hanging from the tree). An oasis in the woods

Perhaps it was just the effect of prolonged exercise or maybe my brain was too tired to think rationally, but this was what can only be described as an otherworldly experience. Anytime I hear those first few notes of Hendrix, I am taken back to that moment, to relive the absolute joy of coming in from the dark to a welcoming party. I can only imagine we were programmed by evolution to prize this exact experience — running out of the darkness into a warm campfire and our fellow hunter-gatherers. In my own small way, I was able to recreate this ethereal moment not on the plains of Africa, but in the woods of Illinois.

The rest of loop 8 passed with — unfortunately — no more otherworldly experiences and by 3 am I had completed 80 miles over 21 hours. As hard as it is to believe, at this point, I almost relished the thought of heading out to be on my own, alternating between extreme suffering and extreme joy in my own universe. I spent the minimum amount of time required to grab some coffee and fuel before going out for the penultimate lap.

Interlude: Do Limits Exist?

While I should have been exhausted after 21 hours of continuous exercise, I did not feel the slightest bit of mental or physical fatigue. The mental side is easy to explain: just the attention required to maintain your footing on the difficult trail kept me mentally engaged. I never lost attention or felt tired because to do so could have meant a premature end to the race. There is nothing more effective to keep you alert than the thought of bodily harm or failure! Coffee was also effective and I think was made more so by the pre-race abstinence.

On the physical side, I struggle to explain how it was possible not to be tired. I don’t think it was because of my training (proper practice is crucial but can’t prepare you for situations like running 24+ hours). Instead, my belief is the human body is capable of far more than we give it credit for. Although you might not think you can go 188 miles in 24 hours, or do 7,600 pullups in 24 hours, humans have done both those things and it’s possible you could as well if you only had the courage to try.

Superheroes are real.

Superheroes are real.

There are (probably) real barriers at some point, but what stops us in practice is almost always mental not physical. If you tell yourself you can only go 5 km, then you’re probably right. Once you hit that 3.1-mile mark, your mind tells your body it’s time to be done and just like that, you’re too exhausted to continue. If you had just told yourself to go further, you would easily have been capable of extending your run. I’ve tried to incorporate this in my training through a technique I call the trick run. Over and over again, starting the night before the run, I tell myself I’m only going for 10 miles, but, once I hit 10, I make myself do another 2. After that, I decide to go for another 2 or 4 miles because my physical capacity is nowhere close to exhausted. This is repeated until I’ve covered 16 or 20 miles.

This point, more than anything else, might be the “one idea” that can help you run an ultramarathon (or do anything hard). No matter how far you’ve gotten, you can always do a little more. In an admittedly unscientific hypothesis, David Goggins calls this the 40% rule. When you think you are at 100% of your capabilities, you are really only at 40%. The exact percentage can be argued, but I think there some truth here: don’t let your perceived limits be your actual limits. Think you can only get an Associate’s Degree? Well good, because that means you’re capable of at least a Master’s if you can only convince yourself to aim that high.

Loop 9: Our Greatest Moments Come From the Most Intense Pain

Lap 9 (miles 80–90), began at 3 am, a time I’ve seen at most 4 times in my life and would feature two highlights, one great and one rough. The good part was at about the halfway point, I ran into my brother, currently on loop 8. I had started out with him but lost him after the first lap and had no idea where he was for the intervening 17 hours. Since neither of us were using our phones, we had no communication and no way to check on the other’s progress. To be honest, I had doubts about my brother’s ability to finish and was therefore pleasantly astonished to see him still going strong (maybe not quite strong but at least still going). He looked to be in good spirits and we ran together for a while before he took off ahead of me (thanks to a burst of strength he attributes to an energy drink. Among many other lessons, this race taught me that caffeine, when used correctly, is truly human rocket fuel).

How could you not smile with this face greeting you in the darkness?

How could you not smile with this face greeting you in the darkness?

Around the time my brother scampered (completely the wrong word choice here) ahead of me, the skies opened up for a 2-hour rainstorm growing from a light drizzle into a full-on downpour. The 6 inches of mud at the start of the race, which, in most places had finally dried, now turned into 12 inches of sucking Earth, ensnaring every footstep. In some downhill sections of the course, I had to sit down and slide down the trail because there was no other way forward. It was guaranteed you would slip and fall at some point and the only question was whether it would end your race. Several times I got lucky enough to avoid injury and my falls resulted in nothing more serious than a thick covering of mud over my entire body. Good.

The 9th loop, run in complete darkness, in the pouring rain, covered in mud, was, without any reservations, my fondest memory of the race. This may seem insane, but it actually illustrates two important points about human existence: many of our best experiences arise out of intense suffering, and, we remember an activity according to what’s called the “Peak-End Rule”. Personally, I will have no way of ever knowing for sure, but I think my experience on miles 80–90 reflects what happens when women experience childbirth. Even though the experience itself must be extraordinarily painful, women willing choose to repeat it. I know the 9th loop “sucked” while I was running it, but I would 100% repeat it even knowing what that entails.

Somehow (something about neurotransmitters perhaps?) the brain turns moments of intense suffering into our most meaningful memories causing us to repeat experiences that would rate as a 10 on the suffering scale. This observation relates to the Peak-End Rule (which has been scientifically verified in experiments), that states our memory of an activity is shaped entirely by the most intense feeling we have during it — the peak — and the feelings at the end of the experience — the end. The most intense experience during the 9th loop was meeting my brother, a pleasant moment. It goes without saying that the ending of every loop is also pleasurable. Hence, even though the average level of pain on miles 80–90 was 90%+, these moments will go down as one of my fondest memories, of the entire race.

Loop 10: Triumph and Vindication

Eventually, the ninth lap did end and with it the rain. I was 10 miles away from achieving a goal I had strived towards for months (in reality I’ve been training to run long distances for almost a decade) and it was now that my brain decided to start acting up again. Having concentrated only on each individual step for the previous 50 miles, I again made the mistake of thinking about the finish. Addressing the problem head-on before it got out of control, I did the only action that would bring me closer to my objective: keep going forward. Instead of my normal 10-minute break at the end of each loop, I took 30 seconds between laps 9 and 10 and headed out for miles 90 to 100.

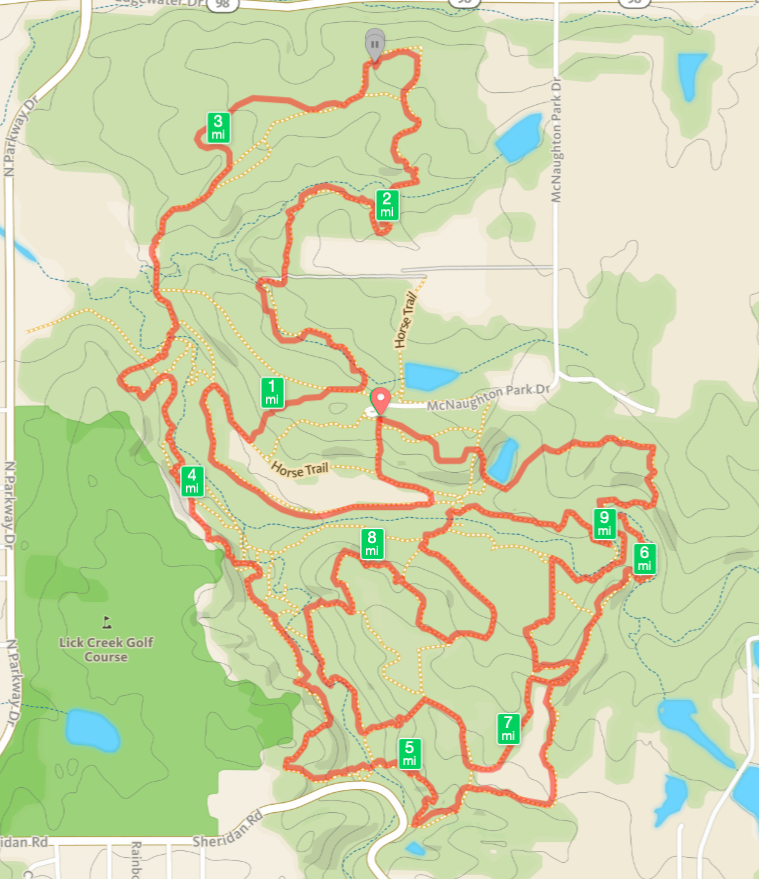

The trail map so you can try it firsthand!

The trail map so you can try it firsthand!

It was just starting to get light again, lifting my spirits as I continued to focus just on the next step. To be honest, there was nothing spectacular about the 10th loop. I kept up my usual eating and drinking and maintained the same 3-hour per lap pace I had for the previous 40 miles. As I passed landmarks — the first aid station, the first creek crossing, the largest hill on the course, the second creek crossing — I felt an unexpected sense of nostalgia. I had formed a kinship with the course and these were sights I wasn’t going to be able to see again (until next year). Nonetheless, I didn’t let sentimentality stop me from continuing forward one step at a time. The most interesting moment was when I stumbled across a hedgehog out for a pleasant morning stroll. I made myself laugh imaging what this hedgehog would have thought if he knew what these two-legged creatures were doing with their free time.

Through a combination of walking, sliding, and running, I reached the final stretch, a 200-yard long flat path through a disc golf course leading to the finish. Although I would like to say I finished in a sprint with my arms raised in triumph, the truth was more mundane. I did run across the finish line, but there was no massive celebration. Instead, the race director gave me a handshake and a congratulations which was echoed by the handful of other people (mostly other runners) at the finish line. Ultra-marathons, especially those without any prize money are decidedly low-key, which is just fine by me. I skipped my college graduation because I didn’t need other people applauding me, and the satisfaction of seeing a job well done is the only reward I need. What matters is if I exceeded my expectations, not if other people watched me doing it.

No crowd, just the way I like it!

No crowd, just the way I like it!

The best word I can come up with to describe how it felt to finish my first 100-mile ultramarathon is sublime. The experience compared to what it’s like to spend hundreds of hours studying for an exam and turning in the exam for a perfect score. All the work you’ve done is vindicated in one moment where you can finally be at peace with yourself. I constantly worry if I am doing enough: should I run more miles, should I study more, should I spend longer at work, but, here at the finish line, after 100 miles and 27 hours, I realized I had finally, at least for now, done enough. The constant striving and sacrifices are all worth it for that one moment of personal triumph when you’ve exceeded your perceived limits.

After finishing, I gathered up my things and headed to the car for a quick nap. While I had completed my run, my most important responsibility was still ahead: somewhere out there, my brother was running and I needed to be there to cheer him on. Fortunately, my dad had come for the final loop and would be able to run/walk with my brother, so I was able to take a 2-hour sleeping break. After waking up right on time, I grabbed a chair and headed to the finish to cheer on my brother. I sat basking in the warm glow of the sun, finally, at least temporarily having quieted my mind. Before too long, my brother and dad came into view and crossed that final stretch, and I smiled, glad my brother would have that same sublime experience of finishing a seemingly impossible challenge.

Brother (on right) finishing with dad (on left). You don’t know how much fun they were having.

Brother (on right) finishing with dad (on left). You don’t know how much fun they were having.

Together, we gathered up our rewards, which ironically, were a pint glass — my brother is too young to drink and I have never ingested alcohol (except at church oddly enough) — and a large silver belt buckle that I don’t think either of us can pull off, and headed home. On the car ride back, I reflected that this was the first day in at least a decade during which I had not looked at either a phone screen or a computer. Mulling it over, I decided it is possible to have a pretty damn good day without any technology.

27 hours of non-stop running for a belt buckle.

27 hours of non-stop running for a belt buckle.

Recovery

How do you recover from a 100-mile race? Simple: you do the exact same training as before the race (only slightly slower). After a drive home and a 4-hour nap, I woke up at 5 pm, a full 8 hours after the race had ended, and headed out with my parents for a traditional family dog walk. I’ve always thought the best way to recover is to act as if nothing happened and keep moving. I went to bed a little earlier than usual, but the next morning saw me up at 5:30 am for a customary 6-mile walk through our neighborhood.

By Wednesday, I was running 8 miles at my usual pace feeling no worse from the 27 hours of running from just a few days before. My brother, on the other hand, took what’s called the horizontal approach to recovery: spend as much time laying down with minimum movement. I’m not sure if my activity was the factor, but I recovered much quicker. The correct answer to how many days should I take off after a race is — at least for me — zero. The human body is designed for movement and the more you use it for its intended purpose, the more it rewards you in terms of overall health and quick recoveries.

Aftermath: Does Ultrarunning Change Your Life?

Ultrarunning by itself does not make you a better person. I can’t stress this enough: someone who spent her weekend volunteering instead of running helped the world a lot more than I did. Running is a selfish sport, with no immediate benefit for anyone other than the athlete. Moreover, I have to thank everyone who supported the race for us selfish runners. There are no individual heroes in ultrarunning, except the selfless volunteers who make the events possible.

The most important activities never get the glory. A shout-out to the wonderful volunteers.

The most important activities never get the glory. A shout-out to the wonderful volunteers.

That being said, there is no doubt that doing hard things makes you better at doing hard things. Moreover, “hard tasks” transcend domains: since the 100-mile run, I’ve drawn on the experience again and again in different areas of my life. When I’m at work and stuck on a hard data science problem, I think back on the race, tell myself “if you can run 100 miles then surely you can solve this problem” and that’s precisely what I do. This run, and the large training commitment it necessitated, has made me better at my job.

Even though running may have nothing to do with my actual career, the same drive that motivated me to go 100 miles is also the drive that allowed me to teach myself data science on my own to achieve my dream job. I would not be in the position I am today without that constant striving to become better inculcated in me by decades of sports training. We should not deify athletes (or any other profession) but we should acknowledge that many of the same features of sports — a constant desire to get better, continuous training over a long period of time, working together to make those around you better, celebrating wins while learning from failures– are characteristics we should try to cultivate in everyone. Ultrarunning has not directly made me a better person, but it has instilled in me a set of traits that I can apply to be a better data scientist, citizen, and family member.

On a personal level, the Potawatomi 100-mile Trail Run will go down as one of the top experiences of my life (just behind earning my dream job at Cortex). Reflecting on the best moments in my life, what they all have in common is that although they may represent a single moment (or 27 hours), they are the culmination of 1000s of hours of training. They required significant sacrifices, but in every case, the things I gave up were more than worth the reward. People today want instant gratification — a tendency amplified by consumerist culture — but the best moments of life require intensive dedication over months or years. Writing a book, learning a new language, running an ultramarathon, training for a better job, are all time-intensive processes but the potential upside from the investment is incredible.

The ultramarathon also served as a reminder that spending money on experiences rather than things is the way to fulfillment. Our society depends on the idea that you can buy your way to happiness through accumulating objects, but looking at people with the most things immediately shows you this is not true. Buying something offers at most a momentary rush of positive emotions followed immediately by the sinking realization that now you have to buy the newer, better gadget to “be fulfilled.” On the other hand, once you have had an experience, no one can take that joy away from you. What’s even better is that the memories of an experience tend to improve over time.

I’ve recently started on a minimalist lifestyle (ironic that I began after moving to New York City, a monument to all things consumerism) and so far it’s working out better than I could have imagined. This may seem only tangentially related to an ultramarathon, but I’ve found many aspects of minimalism intersect with running: a narrowing of one’s focus to only the most important things and an ability to forgo instantaneous bursts of dopamine (when we buy something) in favor of pursuing more meaningful long-term rewards (like learning a new skill). Moreover, when you experience the incredible joy that can come from something as simple as running long distances, you realize there’s no need to buy something to achieve fulfillment.

At the end of the day, all we have is our memories, and these cannot be acquired in a shopping center. Making memories requires going out into the world and doing things — preferably hard things — but it also doesn’t require a lot of money. Once you have those memories, you own them forever, and no one is going to try and convince you to purchase the XL version of the memory. You control your own experiences and hence your memories. If you want a better memory, you’ll have to go out and make it happen.

Final Thoughts

The second most-feared question after “why?” has to be “what’s next?” To be honest, I don’t know right now, which means those voices in my head are starting to raise hell. Have I quieted my mind by running 100 miles? No, not at all, and after much struggling to shut down those thoughts that I’m not the best person I could be, I’ve decided to instead embrace them. Would I be happier with a mind that lets me be mildly content — say a 60 on the happiness scale — at all times, rather than my mind where I am often at a 20 but then sometimes reach a 95? No, and for that I’m glad. All the best experiences in my life have been borne out of intense suffering for a prolonged period. I’d rather experience the troughs and the peaks rather than being stuck in the purgatory of contentment.

Whatever is next, it has to be difficult, and it has to put me out of my comfort zone. It has to require a sustained effort over a significant period of time, and if it involves significant suffering, then that it only a bonus. It also doesn’t have to be only a personal challenge; there are a lot of problems out there to solve, problems that will require sacrifices and long-term effort to overcome. It’s so easy to do the minimum required to get by but the path of least resistance is also the path of least reward.

A few months ago I could have taken the moderate — or god-forbid — easy route and settled into a life of ease. However, I’m glad I didn’t and instead choose to take the strenuous route, opting for suffering over pleasure and long-term gains over short-term temporary happiness rushes. Through the process of training for and running a 100-mile ultramarathon, I have built a trove of reserves I can draw upon when I need to do something hard, a hardened mindset for accomplishing seemingly impossible tasks, the confidence that I can achieve long-term goals, and memories I’ll cherish for the rest of my life. The strenuous path is beckoning: will you take it?

Always choose to go right!

Always choose to go right!

I usually write about data science but occasionally do other interesting things I enjoy sharing with the world. You can reach me on Twitter @koehrsen_will.