Correlation Vs Causation A Real World Example

Viewing real world statistics skeptically

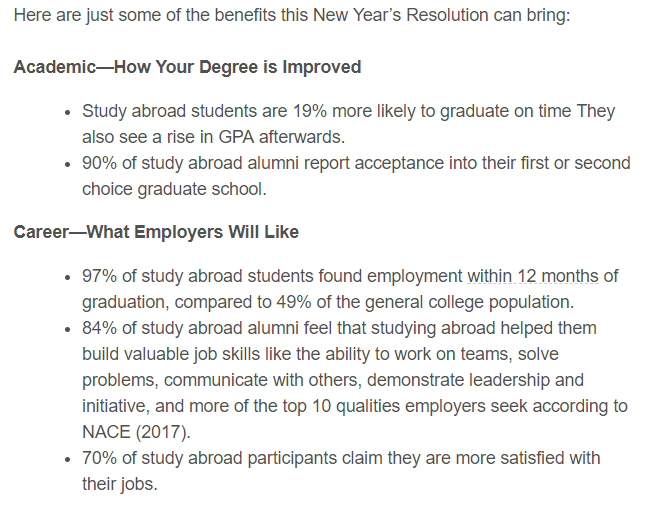

It’s surprising the insights waiting to be discovered deep within the mass of emails we all receive. While mindlessly browsing my inbox, I briefly scanned a message from my University’s Study Abroad office with the following info about the benefits of studying overseas:

What immediately caught my eye was those figures in the 90s — clearly, studying abroad makes you irresistible to grad schools and employers. I was surprised at just how large the academic and career benefits were that came as a result of studying in another country. My second thought was: it’s too bad I didn’t choose to take advantage of those benefits, and I quickly archived the email and before I came to regret any further life decisions. However, something about the information stuck with me. I have been trying to take more time to consciously think through claims and statistics in this fake-news dominated age, and while this wasn’t on the same society-degrading level, something seemed off about the conclusion I had drawn. A few days later while listening to a data skeptic podcast it hit me: I had assumed that studying abroad caused students to have better grades and career prospects, when all the statistics showed was that the two were correlated.

Most of us regularly make the mistake of unwittingly confusing correlation with causation, a tendency reinforced by media headlines like music lessons boost student’s performance or that staying in school is the secret to a long life. Sometimes, especially with health, these tend towards the unbelievable like a Guardian headline claiming a diet of fish leads to less violence.

The work of the powerful tuna lobbying industry

The work of the powerful tuna lobbying industry

The common problem in these articles is that they take two correlated trends and present it as one phenomenon causing the other. The real explanation is usually much less exciting. For example, students who take music lessons may perform better in school, but they are also more likely to have grown up in an environment with a large emphasis on education and the resources needed to succeed academically. These students would therefore have higher school achievement with or without the music lessons. Taking music classes and school performance happen to rise in tandem because they are both products of a similar background, but one does not necessarily cause the other. Likewise, people who stay in school longer typically have more resources which also means they can afford better health care. Most of the time these mistakes are not made out of a deliberate effort to deceive (although that does occur) but out of an honest misunderstanding of the idea of causation. What the statistics, especially those in the study abroad email, show is a selection bias. In each study, the individuals observed do not come from a representative slice of society, but instead are all drawn from similar groups, leading to a skewed result.

Think of the statistics showing students who study abroad are 19% more likely to graduate on time. While it might be possible that studying abroad did somehow motivate lagging students to graduate on time, the more likely explanation is that students who choose to go abroad were those in a better position academically in the first place. They would graduate on time with high GPAs regardless of whether they went to another country. It takes a lot of work and preparation to go to another country to study for a year, and the students who feel confident enough to do so are the ones who are on top of their studies. In this real-world case, the selection bias is towards better students. The sample of students who study abroad is not indicative of students as a whole, rather, it includes only the best-prepared students and therefore it is no surprise that this group has significantly better academic and career outcomes.

The study abroad experience may look great in hindsight, but if we selected only the best students and had them do anything, it would be misleading to say the phenomenon led to better grades. Say for example we own a bottled water company and we want to gather some positive stats to help with sales. We hire a few students to stand outside the honors class and only give our water to the top students. We then conduct a study that shows conclusively that students who drink our brand get better grades. Because we selected a specific group of subjects to include in our study, we can make it look as though our water caused an increase in grades.

The study abroad statistics come from what is known as an observational study. Rather than constructing an experiment, an observational study observes some process in the real world with no cannot control over the independent variable, in this case the students who chose to study abroad. Observational studies cannot prove cause and effect, only associations between different factors (such as achievement and studying in another country). In order to prove one process caused another requires a randomized controlled trial with subjects represent the entire population. In this case, carrying out a randomized controlled trial would require selecting a random subset of students across the range of academic performance, sending some to study abroad, and keeping a control group home. We could then analyze the results to determine if there were significant differences between the two groups. If there was, then we would probably carry out more studies controlling for more variables, until eventually we were satisfied there was no hidden effects and we could establish a causal relationship.

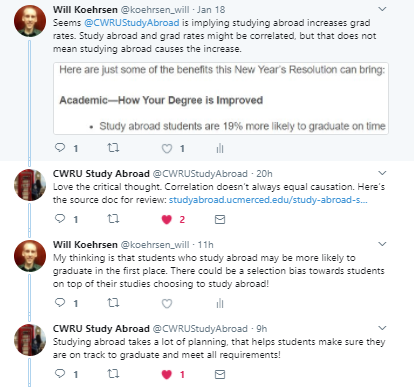

I pointed these observations out to the CWRU Study Abroad Office and what followed was a decent and productive conversation.

Civility and Honest Discussion. On Twitter!

Civility and Honest Discussion. On Twitter!

By posting about this, I was not trying to call out the office. Although the email did state: “Here are just some of the benefits this New Year’s Resolution can bring,” it wasn’t claiming an exact cause and effect. However, when a single topic is presented surrounded by a sea of facts, our natural inclination is to draw a causal link, a tendency marketers and companies take advantage of with regularity. I believe all the statistics in this case are valid, but we still need to avoid assigning a cause and effect relationship. Without randomized controlled trials, we cannot say one activity caused another, and all we can claim is that two trends are correlated.

This is a small example, but it illustrates an extremely critical point: all of us, even grad students who use these concepts every single day, can be fooled by statistics. Humans naturally see patterns where they don’t exist, and we like to tell a cohesive story about what we think is going on (the narrative fallacy). However, the world usually does not have defined causes and effects, and we must settle for correlations. This view of the world may make headlines less exciting (it turns out chocolate is not a miraculous food), but it means you will not be fooled into buying products or taking actions that are not in your best interest due to questionable evidence. Moreover, we can share our experiences with others and create a skeptical community in which we make sound decisions for our benefit and not for a company’s bottom line.

As always, I welcome constructive criticism and feedback. I can be reached on Twitter at @koehrsen_will.