Most People Screw Up Multiple Percent Changes. Here's How To Get Them Right.

Solving a Common Math Problem with Everyday Applications

Incredibly, after 16 years of schooling, the majority of American college students get this question wrong:

What is the total percentage change in the following situation?

Decrease of 40% followed by an increase of 60%.

A. Increase of 10%

B. Increase of 20%

C. Decrease of 4%

D. None of the above.

The answer, of course, is C, an overall decrease of 4%. Not only did the majority of college students get this question wrong, they did not even get the correct direction, with over half guessing this was an increase. The common error is taking the percentages at face value and adding them together to get the overall percentage change. We thus have another entry in the long list of things people aren’t very good at, combining multiple percentage changes.

Far from being an abstract, theoretical idea, finding a total change from a sequence of percentage moves has implications in our daily lives from the price of consumer goods to national budgets to our retirement account value, to the battery life on our newest laptop. Yet, despite the ubiquity of the error and the ramifications for us personally and as a nation, we are incapable of teaching people how to correctly stack percentages. In this article, we’ll discuss what the error is, how to avoid it, why this matter, and why people make it. Our primary resource is the paper: “When Two Plus Two Is Not Equal to Four: Errors in Processing Multiple Percentage Changes” (link).

What’s the Problem?

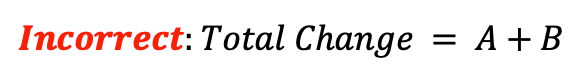

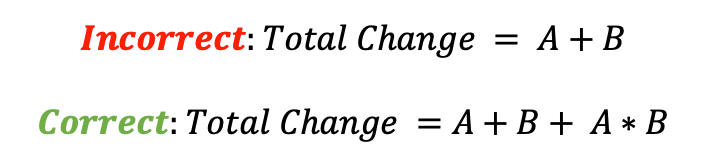

The error is that when we see two consecutive percentage changes, we instinctively take them at face value and add them together to get a total change. Thus, a discount of 50% followed by a discount of 25% is interpreted as 75%. In equation form, for two percentages A and B, the mistake is:

The common error of adding two percentage changes at face value.

The common error of adding two percentage changes at face value.

The problem is a percentage is calculated from a specific base value. After the first percentage change, the base changes, and the second percentage does not have the same base. Two percentages that have different base values cannot be directly combined by addition! Instead, we have to work out the percentage changes separately.

How to Avoid the Error when Combining Percentage Changes

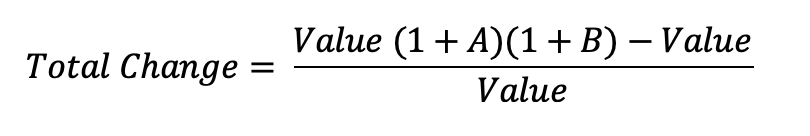

First, calculate the new base from the first percentage change, then, using the new base, calculate the percentage change from the second. The overall percentage change can then be calculated from the new value and the original base value. In equation form, the overall percentage change is:

The correct method for calculating total changes from two individual percentage changes.

The correct method for calculating total changes from two individual percentage changes.

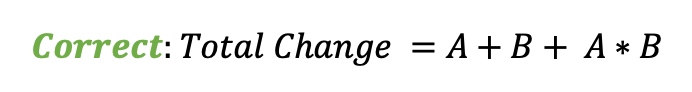

Canceling out the value yields the simpler equation for total percentage change from two sequential percentage changes A and B:

Total Percentage Change from Two Sequential Percentage Changes

Total Percentage Change from Two Sequential Percentage Changes

The error is in the extra term on the end, A * B. The fortunate part of the mistake is it always occurs in a systematic direction:

- For 2 increases, we underestimate the overall percentage increase

- For 2 decreases, we overestimate the total percentage decrease

- For 1 increase and 1 decrease resulting in an overall increase, we overestimate the total percentage increase

- For 1 increase and 1 decrease resulting in an overall decrease, we underestimate the total percentage decrease

Let’s work through examples representing these 4 situations:

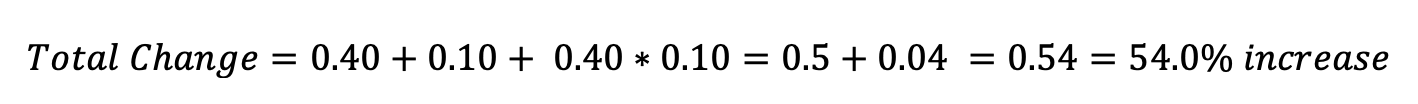

- 2 increases: suppose the battery life of a smartphone goes up 40% in one year and 10% in the next. What’s the total change?

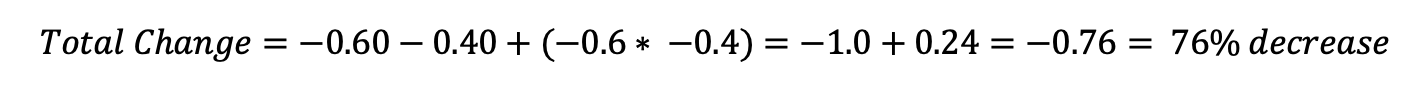

2. 2 decreases: suppose the town tax rate decreases by 60% and then by 40% (we can only wish). If we add the 2 together, we pay 0% tax but surely that can’t be right! Indeed it isn’t:

2. 2 decreases: suppose the town tax rate decreases by 60% and then by 40% (we can only wish). If we add the 2 together, we pay 0% tax but surely that can’t be right! Indeed it isn’t:

There’s no such thing as a free lunch.

There’s no such thing as a free lunch.

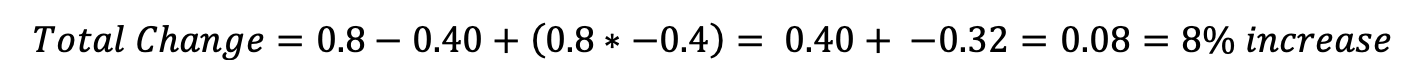

3. 1 increase and 1 decrease resulting in an overall increase. Suppose national spending increases by 80% one year and then decreases by 40% the next. What’s the total change?

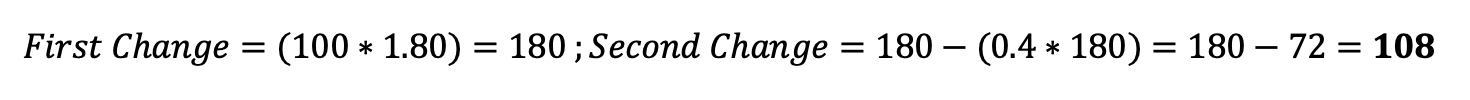

Notice that the order of the changes does not matter. We could decrease first and then increase, but the overall magnitude of the change is the same. If you don’t believe me, start with spending of $100. The first order works out:

Notice that the order of the changes does not matter. We could decrease first and then increase, but the overall magnitude of the change is the same. If you don’t believe me, start with spending of $100. The first order works out:

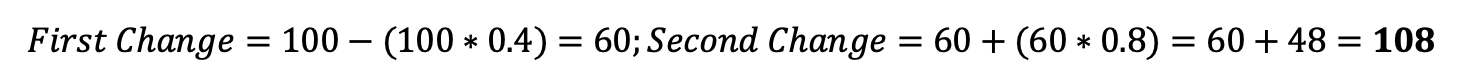

The decrease followed by the increase gives the same answer:

The decrease followed by the increase gives the same answer:

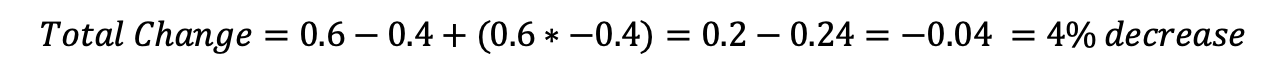

4. 1 increase and 1 decrease resulting in an overall decrease. Suppose the length of a blog post increases by 60% during the first edit and decreases by 40% during the second (this is the same situation as the initial question). Did the post get longer?

4. 1 increase and 1 decrease resulting in an overall decrease. Suppose the length of a blog post increases by 60% during the first edit and decreases by 40% during the second (this is the same situation as the initial question). Did the post get longer?

In the last case, adding the two percentages gets you a 20% increase in what was actually a 4% decrease. Had you made the common error, you would have ended up on the wrong side of 0! A similar error occurred when standardized test scores in California decreased by 60% one year and increased by 72% the next, resulting in praise for the raising of student scores from the baseline. Not to be a downer, but the total overall change — wait, work this one out yourself — was a 31% decrease in test scores. Students were worse than 2 years previous not better, and their parents were still math illiterate (but not you anymore!).

In the last case, adding the two percentages gets you a 20% increase in what was actually a 4% decrease. Had you made the common error, you would have ended up on the wrong side of 0! A similar error occurred when standardized test scores in California decreased by 60% one year and increased by 72% the next, resulting in praise for the raising of student scores from the baseline. Not to be a downer, but the total overall change — wait, work this one out yourself — was a 31% decrease in test scores. Students were worse than 2 years previous not better, and their parents were still math illiterate (but not you anymore!).

Why Does this matter?

All of the above were hypothetical examples of very real situations. Knowingly or not, we deal with multiple percentage changes all the time and when we don’t realize this, it’s usually to our detriment. As with most other human errors, there are people already taking advantage of it for their benefit. (It’s a good rule of thumb that errors in human logic are discovered first in marketing and only later are they published in academic journals. For more on this, read Influence by Robert Cialdini. )

For example, look at the “double discount”. This occurs often in retail where you can take an extra 25% off an item on sale for 50% off. The salesperson wants you to add the percentages and conclude the discount is 75% instead of the more modest 62.5% discount for the actual value. Or consider a computer with a display that has 20% more pixels than the last model which had 30% more than the previous. Instead of presenting these increases separately — where adding gets you to 50% — the seller would be better off presenting them as one number, 56%, which is the actual increase.

What the salesperson would be doing in these situations is framing: presenting information in a context to get us to make a decision in her favor. Any piece of data can be presented in multiple ways — for example, a medication can be described as having 10% chance of causing a side effect or as having a 90% chance of causing no side effects (the framing here is positive versus negative). Multiple percentage changes are only one example of framing, which has a profound impact on our choices (read about framing in “The Framing of Decisions” by Tversky and Kahnemann).

One of the studies in the paper “When Two Plus Two” looked at the effect of in a retail setting of presenting a discount as a single decrease or two percentage discounts. Not surprisingly, the double discount generated more purchases, more revenue, and more profit than the equivalent single discount. While this was only a single study, the prevalence of double discounts in stores is strong evidence marketers had already figured out and were using this cognitive shortcoming.

A basic principle is when we refuse to do the math ourselves, we will be fooled by someone who has done it.

Why Does This Happen?

One theory that explains why we are bad at percentages — as well as fractions and decimals — is that humans evolved math skills only dealing with whole numbers. “Whole number dominance” makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint: things in nature really only come in whole numbers. We’re never chased by 1.7 mountain lions or must have 2.5 children to carry on the species. Over millions of years, we got pretty good at adding together whole numbers. In more complex situations — calculating the compound percentage return on your retirement account — our evolved abilities don’t hold up well.

I think the mistake in calculating percentage changes is a combination of our predilection for whole numbers and remaining in system one thinking. If you’ve read works like “Thinking, Fast and Slow”, then you are familiar with the concept of the two systems of thinking. The first is a quick, instinctual judgment made using a set of heuristics and biases (mental shortcuts). The second mode is a prolonged, rational decision made by reasoning through multiple pieces of information. The first system works well for situations our ancestors encountered but breaks down in information-rich, constantly changing environments, exactly where we find ourselves now.

Calculating the total effect of multiple percentage changes requires switching from 1 to 2 which is effortful and something we try to avoid. Unfortunately, system 1 seems incapable of multiplication and takes a shortcut — addition — to calculate that a 50% and 25% increase is 75% instead of 87.5%.

Another of the studies in “When Two Plus Two” looked at when we do the multiple percentage calculation correctly. Interestingly, they found we unconsciously make an effort vs payoff tradeoff and only stop to calculate the correct answer when the payoff is worthwhile (for this study, a couple of dollars for the right solution). We should be careful about extrapolating from a single study, but external rewards (sometimes) motivate us to work harder.

Similarly, when the percentage changes were easy to compute, say a 20% decrease and a 10% decrease (total of 18% decrease), the error rate went down. Thus, either lowering the effort or increasing the payoff seems to result in more accurate calculations. The third situation where the error rate decreased was when the total from adding percentages was clearly not possible, as with discounts of 80% and 40%. People know that the price of a product cannot decrease by 120% or they would have to be paid to buy it!

In summary, we incorrectly calculate multiple percentage changes because it requires effort to reason through the right answer. We are good at adding and using whole numbers, but not so good with multiplication and percentages. The solution is just as straightforward as the problem: take the time to carry out calculations for yourself instead of assuming the answer. Most important decisions in our world requiring recruiting system 2, so you might as well train it at every opportunity!

Conclusions

The multiple percentage change error occurs when we take percentages at face value and add them together. The correct approach is to carry out the calculations separately or use the right formula:

It’s the details — in this case the A * B — that make the difference.

It’s the details — in this case the A * B — that make the difference.

Applying the right equation will let you see that double discounts are not as large as they seem, double increases are larger than they appear, and to make up for a 60% decrease requires not a 60% increase, but a 150% increase!

Yes, it may take a little more effort, but when you are not willing to do the math yourself, it means you will lose out to those who do. I hope that even if your self-confidence took a 40% hit at the beginning of this article, it has since increased by 90% to come out 14% positive.

As always, I welcome feedback and constructive criticism. The best place to reach me is on Twitter @koehrsen_will.