The Power of I Don’t Know

Intellectual humility is not a weakness but a strength

The phrase “I don’t know” has almost disappeared from our discourse. From the job applicant who must claim to have mastered 100 different skills to politicians who need to have a confident opinion on every news event, the modern world does not encourage people to admit when they lack knowledge or skills. However, by refusing to acknowledge our ignorance, we limit our chances for personal improvement. Saying “I don’t know” — practicing intellectual humility — and adopting a growth mindset are powerful means for becoming smarter and more skilled individuals.

The Dangers of Certainty

When we are young, we refuse to say we don’t know something because we’re ignorant of our own ignorance. We simply have no conception that the world extends beyond our sphere of knowledge, an idea that should be — but often isn’t — disproven in school. Although we are naturally curious — think about the endless “why?” questions asked by children — school teaches us there are a set of certain facts about the world to memorize, focusing on the limited amount of current human knowledge rather than discussing how we continually discover new knowledge that reveals our past beliefs to be incorrect. Moreover, we’re taught to not question these facts, and if we don’t know one of them, the best response is to guess!

Once the curiosity has been driven out of us in school and we go into the workforce, we’re even less likely to say “I don’t know”. We perceive a lack of absolute confidence, especially in our leaders, as a weakness. Despite the uncertainty that comes with living in a complex world, we are afraid to admit when we don’t know something for sure and we therefore don’t expect to see uncertainty expressed by others. From economic statistics such as the jobless rate to election forecasts, we like to see a single number in news stories even when the real answer is a wide range of possibilities (this has been dubbed the lure of incredible certitude). It’s far more comfortable for someone to feign certainty than admit to the nuance in a real-world situation.

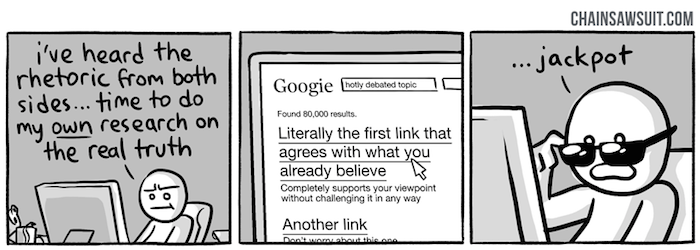

When people refuse to admit what they don’t know, confirmation bias comes into play as people deliberately seek out evidence that confirms their supposed knowledge and avoid that which might show they don’t know enough to make a rational decision.

Confirmation Bias is caused by an over-confidence in our beliefs.

(Source)

Confirmation Bias is caused by an over-confidence in our beliefs.

(Source)

At all ages and level of society, an inability to admit the limits of our expertise is disastrous: personally, I’ve spent way too much time trying to learn new software or techniques on my own rather than admit I was out of my league and seek out help from those with more knowledge. On the national scale, decisions as monumental as that to invade another country (see the Iraq War) are made because individuals have more confidence than is warranted in their beliefs and refuse to admit there is uncertainty in the situation.

Examples of the perils of certitude abound: In a Freakonomics Podcast episode, the hosts discuss a case in which a business spent hundreds of millions on an ineffective advertising campaign because they refused to even ask if it was working. Moreover, refusing to admit when we don’t have a skill can have negative consequences. Think of the job applicant with the inflated resume. Once on the job, they’ll have to take the energy to maintain the facade that they know more than they do until it becomes unsustainable and they have to actually learn the skill. It would be much better for everyone involved if the candidate was honest and (if awarded the job) arrived ready to learn on the first day.

Considering the potential downsides of failing to say “I don’t know”, it’s pretty clear that this phrase should be a part of our vocabulary. However, given the difficulty of saying those words — what the Freakonomics hosts claim are the 3 hardest words to say in the English language — perhaps “I don’t know” needs a rebranding. The phrase intellectual humility is a better choice as it lacks the negative associations. Furthermore, it encompasses both the idea of not having complete knowledge, and even when you do know something, admitting that there is uncertainty involved.

Intellectual humility also fits in nicely with the most crucial part of the “I don’t know” approach: what you do after saying those words. Whatever we call it, asserting your own lack of knowledge or skills by itself is necessary, but it’s only the first step. The true benefits of “I don’t know” come when we start working to address our deficiencies.

The Two Kinds of I Don’t Know

Consider two different approaches to the following scenario: your boss has asked you to try and automate some routine data entry tasks to save you and your coworkers hours of tedium.

The first approach is what we’ll call the defeatist mindset: deterred by your lack of programming knowledge, you tell your boss “I don’t know enough to do that, I think someone else should take it on.” In the defeatist mindset, “I don’t know” is used as an excuse for not completing a task. Much as its name suggests, the defeatist mindset is not a productive form of “I don’t know” — it prevents you from learning new skills keeping you stagnant in your job.

Contrast this with what happens when you adopt a growth-driven attitude. This time, when your boss asks the question, your response is “I don’t know but I would enjoy the opportunity to learn.” Within a few days, you have learned enough Python to automate the data entry, saved your co-workers dozens of hours per week, earned yourself a promotion, and opened up many opportunities thanks to your newly acquired skills.

The growth-driven version of “I don’t know” turns a lack of knowledge into an opportunity for personal improvement. You currently lack the knowledge or skills but you’re willing to work to acquire them.

The definition of the growth driven mindset is that talents can be developed with effort and commitment. This is in contrast to the fixed mindset where one believes that talent is innate and thus there is no reason to try and improve oneself if you don’t already have the skills. Saying I don’t know — using intellectual humility — is the necessary first step of the growth driven mindset. Once you’ve admitted what you don’t know, there is still a lot of work left, but at least you are open to the idea of improving.

Acting on the growth driven mindset requires the crucial ability to see where you are now (what you don’t know), where you would like to be in the future (what you want to learn), and then forming a plan to get from here to there.

- Admit your own ignorance

- Figure out what you want to learn

- Make a plan to learn the skills or knowledge

- Execute on the plan a little at a time

The defeatist mindset is easy and natural: as humans, we are always looking for the easy option, which means staying in our current position. The growth-driven mindset requires not only admitting the limits of our own knowledge, but also committing ourselves to a long-term plan. It also might necessitate going out of our comfort zone. However, the alternative is to stay in the same rut, doing the same job using our current skills or rehashing our same opinions because we haven’t bothered to question them with new evidence.

Although people believe that the phrase “I don’t know” symbolizes a character shortcoming, it requires much more self-confidence to take the high road and admit when you don’t know something, especially to others. Once you’ve admitted a lack of knowledge or skills, the next step is correcting that deficiency.

The Power of Intellectual Humility

One of the best examples of the power of “I don’t know” is the entire scientific enterprise. Science is founded on admitting when we don’t know something and then gathering evidence to figure out the cause of a phenomenon or the effect of a treatment. A great way to be wrong in science is to proclaim that everything is already known. In a famous quote (often misattributed to Lord Kelvin), the Nobel Laureate Albert Michelson stated in 1894:

The more important fundamental laws and facts of physical science have all been discovered, and these are so firmly established that the possibility of their ever being supplanted in consequence of new discoveries is exceedingly remote.

Within 20 years of this statement, both quantum mechanics and relativity would shake the foundations of physics and lead to such developments as GPS and all modern electronics. As another example, traditional religious beliefs held that the Earth was at the center of the Universe — no question, nothing to debate. Yet, when scientists such as Galileo admitted humanity’s ignorance and started to investigate, they found a much more magnificent and wondrous universe than that offered by any religion.

What you get when you admit you don’t know but you want to find out.

(Source)

What you get when you admit you don’t know but you want to find out.

(Source)

Scientists must be well-practiced in recognizing when they don’t know something and figuring out a way to rectify that shortcoming. The best scientists are able to harness natural human curiosity and use it to direct their research efforts. Perhaps no scientist exemplified this better than Richard Feynman, the charismatic physicist who was driven to answer questions he personally found interesting because he liked “finding things out”.

Even for those of us who aren’t scientists, the evidence shows that we would be better off by recognizing our limits and adopting a growth mindset. In a study of students, those with more intellectual humility — the ability to say they didn’t fully understand a topic — had better learning outcomes in part because they were more willing to seek out the extra needed. Intellectual humility and the growth mindset go hand-in-hand: if you believe that you can acquire any new skill, then you’ll be more willing to admit that you’re not quite yet where you want to be which is perfectly fine!

Conclusions

Saying I don’t know is not an admission of weakness but a power: not only will it mean you’ll be wrong less often, but it will lead you to greater personal improvement in the future. Adopting a practice of intellectual humility and in turn a growth mindset — while not easy — will lead to better long-term performance in school, work, and in your personal life.

If saying I don’t know or expressing uncertainty is too difficult, try to rephrase it in terms of intellectual humility. “I don’t know how to program” becomes “learning to program is next on my list.” Or, “I don’t know the exact sales numbers for last month” can be phrased as: “we’re still working to get the numbers correct but here are our upper and lower estimates.” Although it’s a cliche, the best policy in any situation is really full admission of the truth because it prevents you from having to maintain a facade of lies and deal with the fallout when the truth is discovered.

“I don’t know” may at first sound defeatist, but in reality, when followed by “but I’m going to find out” it is an extremely optimistic phrase. It implies that you have the ability to change yourself for the better. Even while the rest of the world seems to grow more certain, admitting the limits of your current abilities will put you on a long term path for greater future improvement. Learning is one of the most impressive feats that can be accomplished by humans, and every utterance of “I don’t know” is another chance to learn.

As always, I welcome feedback and constructive criticism. I can be reached on Twitter @koehrsen_will or at my personal website willk.online.