Practical Advice for Data Science Writing

Useful tips for writing about your data science projects

Writing is something that everyone wants to do more of, yet we often find it difficult to get started. We know that writing about data science projects improves our communication abilities, opens doors, and makes us better data scientists, but we often struggle with thoughts that our writing isn’t good enough or that we don’t have the necessary background or education.

I’ve struggled with these feelings myself, and, over the past year, have developed a mindset to get through these barriers as well as general principles about data science writing. While there is no one secret to writing, there are practical tips that make it easier to establish a productive writing habit:

- Aim for 90%: the imperfect project that gets finished is better than the perfect project you never complete

- Consistency helps: the more you write, the easier it gets

- Don’t worry about credentials: in data science there are no barriers to prevent you from contributing or learning anything you want

- The best tool is the one that gets the job done: don’t over-optimize your writing software, blogging platform, or development environment

- Read widely and deeply: borrow, remix, and improve on other’s ideas

In this article, we’ll go through each point these briefly, and I’ll touch on ways in which I’ve implemented them to improve my writing. Over the course of dozens of articles, I’ve made lots of mistakes, and, rather than making these same errors yourself, you can learn from my experiences.

Perfection is Overrated: Aim for 90%

The biggest mental obstacle I’ve had to overcome and what I commonly hear others struggle with is the idea that “my writing/data science skills aren’t good enough.” This can be debilitating: when considering a project, people will rationalize that since they can’t achieve perfection, they might as well not even start. In other words, they let the perfect become the enemy of the good.

The fallacy here is that only an immaculate project is worthy of being shared. However, a rough-around-the-edges project that gets completed is far better than the idealized project that can never be finished.

While flawless performance is to be expected is some domains — you want your car brakes to work every single time — blog writing is not one of these areas. Think about the last time you read a data science article. I’m guessing (especially if you read one of my articles) it had at least a few errors. However, you probably finished the article anyway because what matters is the value of the content. We’re willing to overlook a few mistakes as long as the article has compelling content.

When I write, I aim to make my articles readable and do several edits, but I have stopped demanding that they be entirely free from errors. In practice, I aim for 90% and anything above that is a bonus. Putting out an article with a few errors is better than putting out none at all (and if you are concerned with grammar / style, I recommend the free tool Grammarly).

This attitude extends beyond writing to a data science project itself. There will always be another method you can try or another round of model tuning to carry out. At a certain point, the returns from this work will be less than the time invested. Knowing when to stop optimizing is an important skill. Don’t let this be an excuse for a half-finished project, but don’t stress trying to attain an impossible 100%. If you’ve made a couple mistakes, then you have opportunities to learn by putting your work out for feedback.

Be willing to put out imperfect work and respond positively to constructive criticism so you don’t make the same mistakes the next time.

You Don’t Get Better by Doing Something Once: Consistency Counts

While the 10,000 hour rule has been debunked (it turns out that focusing while you practice, called “deliberate practice”, matters at least as much as how much you practice) there is something to be said for accumulating more experience at a task. Writing is not an activity requiring special abilities, but rather a process that requires repetition to master.

Writing may not ever be simple, but it does get easier to do as you practice. Moreover, writing is a positive feedback loop: as you continue to write, it gets easier and your writing gets better, leading you to want to write more.

A significant barrier to my writing is getting started, what I like to think of as activation energy. As you write more often, that barrier to beginning is lowered and you reduce the amount of friction needed to start writing. Then once you’ve started, you’re usually past the hardest part.

If you write consistently, you can change your mindset from “now I’m going to *have *to take time from this other activity to write “ to “now that I’ve finished the project, it’s time to write about it as usual.” Even writing about failed projects can be valuable. Writing about every project reinforces the concept that writing isn’t an extra chore but a critical part of the data science pipeline.

Writing often doesn’t just mean sharing articles. While you’re working on an analysis, try adding more text cells explaining your thought process to your Jupyter Notebook. This is how I initially got around to writing a blog: I started annotating my notebooks thoroughly and realized to get to an article was only a little more work. Moreover, when you start adding explanations to your code, your future self and co-workers who look at your work will thank you.

Writing my first few articles did feel like a chore, but as I got used to the idea that this wasn’t going to be a one-off thing, it became much easier until I reached the point where it was an accepted part of my workflow. Habit is extremely powerful, and writing can be acquired like any other habit.

Titles are Meaningless in Data Science: Don’t Worry about Credentials

Think about the last time you installed a Python package or forked a repo from GitHub. Did you search by authors who had an advanced degree? Did you only look at code written by professional software engineers? Of course not: you looked at the content of the repository before even checking the credentials of the author (if you bothered to at all).

The same concept applies to data science articles: they are judged by the quality of the work and not on the author’s credentials. On the internet — for better and occasionally for worse — there are no barriers to publishing. There are no arbitrary certificates needed, no ivory tower to climb, no examinations to pass, and no gatekeepers preventing you from learning and writing about anything in data science. While a college degree in *something *is useful (I have a degree in mechanical engineering and don’t regret it despite never using it) it is certainly **not necessary **to contribute to data science.

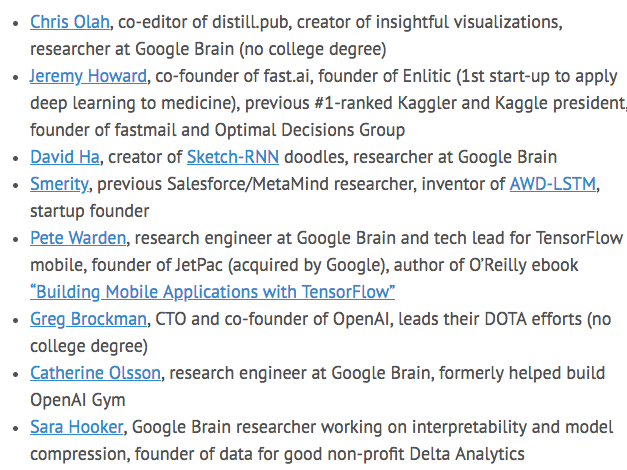

In this excellent article, Rachel Thomas, a professional machine learning researcher gives her opinion as to why an advanced degree is not necessary even in deep learning. Here is a partial list she made of contributors to deep learning without a PhD:

A partial list of contributors to deep learning who don’t have a PhD.

(Source)

A partial list of contributors to deep learning who don’t have a PhD.

(Source)

In data science, your ability to acquire new knowledge is more important than your education background. If you don’t feel confident about a subject, then there are a plethora of resources to learn what you need to know. I can personally recommend Udacity, Coursera, and the excellent Hands-on Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn and TensorFlow as my favorite resources, but there are countless others. While MOOCS haven’t fully “democratized education” in all subjects, they have been successful for data science.

Don’t stop yourself from taking on a project because you think you don’t have the background. I initially worried about my credentials, but after I thought about it from the reader’s side —people don’t consider the title of someone before reading their article online — it became much easier for me to publish without worrying about my background. Also, once you realize that where your education is from doesn’t matter, you’ll find it much easier to learn because you can stop thinking of formal education as the only reservoir of information. For data science, you can learn everything you need from the internet, often much quicker than you would be able to in a classroom.

It’s also important to stay open-minded: I try to admit in my articles when I’m not entirely sure I’m using the right method and I always welcome any corrections. There is no standard method to do data science but you can still learn a lot from others who have experience solving similar problems.

Recognize that you can learn anything necessary to take on any data science project on your own, but also remain open to advice.

The Best Tool is the One that Gets the Job Done

Windows vs MacOS. R vs Python. Sublime vs Atom vs PyCharm. Medium vs your own blog. These arguments are all unproductive. The correct response is to use whatever tool lets you solve the problem (within the confines of your environment). Moreover, the tool with more options is not always better.

While more features can sound great, they often get in the way of you doing work. Generally, I try to keep things as simple as possible. When people ask me for recommendations for a writing platform, I say Medium because it has a limited amount of features. When I write, I want to focus on the content instead of spending time trying to format everything exactly as I want.

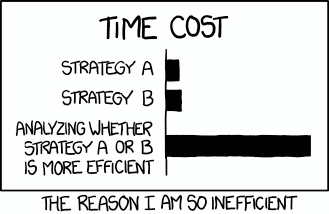

More customization options means more time customizing those options and less time doing what you should be doing — writing or coding.

I’ve gotten stuck in the tool optimization loop before: I’ve been persuaded to switch to a new technology and spent time to learn the features only to be told that this technology is obsolete and the next thing will make me even more productive. I stopped switching between IDEs (integrated development environments) a while ago and just settled on Jupyter + Sublime Text because I realized the extras were only getting in the way writing code.

I’m not opposed to switching tools when the argument is strong enough, but switching just for novelty is not a recipe for productivity. If you really want to get started, pick a stack and stick with it. If you start a project and notice something missing from your tools, then you can start looking for what you need. Don’t fall for the flashy new tool promising more features until you know you need those features (this also applies to buying a car). In other words, don’t let optimization of a work routine get in the way of doing work.

Choose a strategy and stick with it! (Source)

Choose a strategy and stick with it! (Source)

Where to Get Your Ideas: Read Widely and Deeply

Great ideas don’t emerge on their own, isolated from all others. Instead, they’re created by applying old concepts to new problems, mixing two existing ideas, or improving upon a proven design. The best way to figure out what to write about is to read what other data scientists are writing. When I’m stuck on a problem or need some new writing ideas, I inevitably start reading.

Moreover, if you aren’t confident about your writing style, start by emulating your favorite writers. Look at the structure of their articles, and how they approach problems and try to apply the same framework to your project and article. Everyone has to start somewhere, and there is no shame in building on the techniques of others. Eventually you’ll develop your own writing style which someone else can then adapt and so on.

I recommend reading both widely *and *deeply *in order to balance exploration versus exploitation.The explore / exploit problem is a classic in machine learning, particularly in reinforcement learning: we have an agent that needs to balance learning more about the environment, *exploring, versus choosing actions based on what it believes will lead to the highest reward, exploiting.

By reading widely, we explore many different areas of data science, and by reading deeply, we develop our understanding of a particular area of expertise. You can apply this to your writing and data science by practicing the skills you already have — exploiting — and frequently learning new ones — exploring.

I also like to apply the idea of explore / exploit to choosing a data science project. Both extremes can lead to unsatisfactory projects: select a project based only on what you’ve done in the past, and you might find it stale and lose interest. If you choose a project where you can’t apply any prior knowledge, then you can get frustrated and give up. Instead, find something in the middle, where you know you can build up those skills you already have, but also need to learn something new.

My final advice for choosing a project is to start small. Projects only grow as you work on them, and no matter how much time you allotted to the project, it will take longer (Hofstadter’s Rule). It might be tempting to take on a complete machine learning project, but if you are still trying to learn Python, then you probably want to tackle one piece at a time. That being said, if you are confident enough to take on an entire project, then go for it! There is no more effective method for learning than practice, especially putting all the pieces together in one problem.

Conclusions

As with any activity with delayed long-term rewards, writing can be difficult at times. Nonetheless, there are concrete actions which make the process easier and create positive feedback loops. There is no one secret to writing, but rather a sequence of steps that reduce the friction to get started and help you keep going. As you work to start or advance your data science career, keep these tips in mind to establish and maintain a productive writing habit.

I welcome discussion on writing advice, comments, and constructive criticism. I can be reached on Twitter @koehrsen_will.