What I Learned From Writing A Data Science Article Every Week For A Year

School of Athens by Raphael (Source)

School of Athens by Raphael (Source)

Lessons on the life-changing power of data science writing

There ought to be a law limiting people to one use of the term “life-changing” to describe a life event. Had a life-changing cup of coffee this morning? Well, hope it was good because that’s the one use you get! If this legislation came to pass, then I would use my allotment on my decision to write about data science. This writing has led directly to 2 data science jobs, altered my career plans, moved me across the country, and ultimately made me more satisfied than when I was a miserable mechanical engineering university student.

In 2018, I made a commitment to write on data science and published at least one article per week for a total of 98 posts. It was a year of change for me: a college graduation, 4 jobs, 5 different cities, but the one constant was data science writing. As a culture, we are obsessed by streaks and convinced those who complete them must have gained profound knowledge. Unlike other infatuations, this one may make sense: to do something consistently for an extended period of time, whether that is coding, writing, or staying married, requires impressive commitment. Doing a new thing is easy because our brains crave novelty, but doing the same task over and over once the newness has worn off requires a different level of devotion. Now, to continue the grand tradition of streak completers writing about the wisdom they gained, I’ll describe the lessons learned in “The Year of Data Science Writing.”

The five takeaways from a year of weekly data science writing are:

- You can learn everything you need to know to be successful in data science without formal instruction

- Data science is driven by curiosity

- Consistency is the most critical factor for improvement in any pursuit

- Data science is empirical: instead of relying on proven best methods, you have to experiment to figure out what works

- Writing about data science — or anything —is a mutually beneficial relationship as it benefits you and the entire community

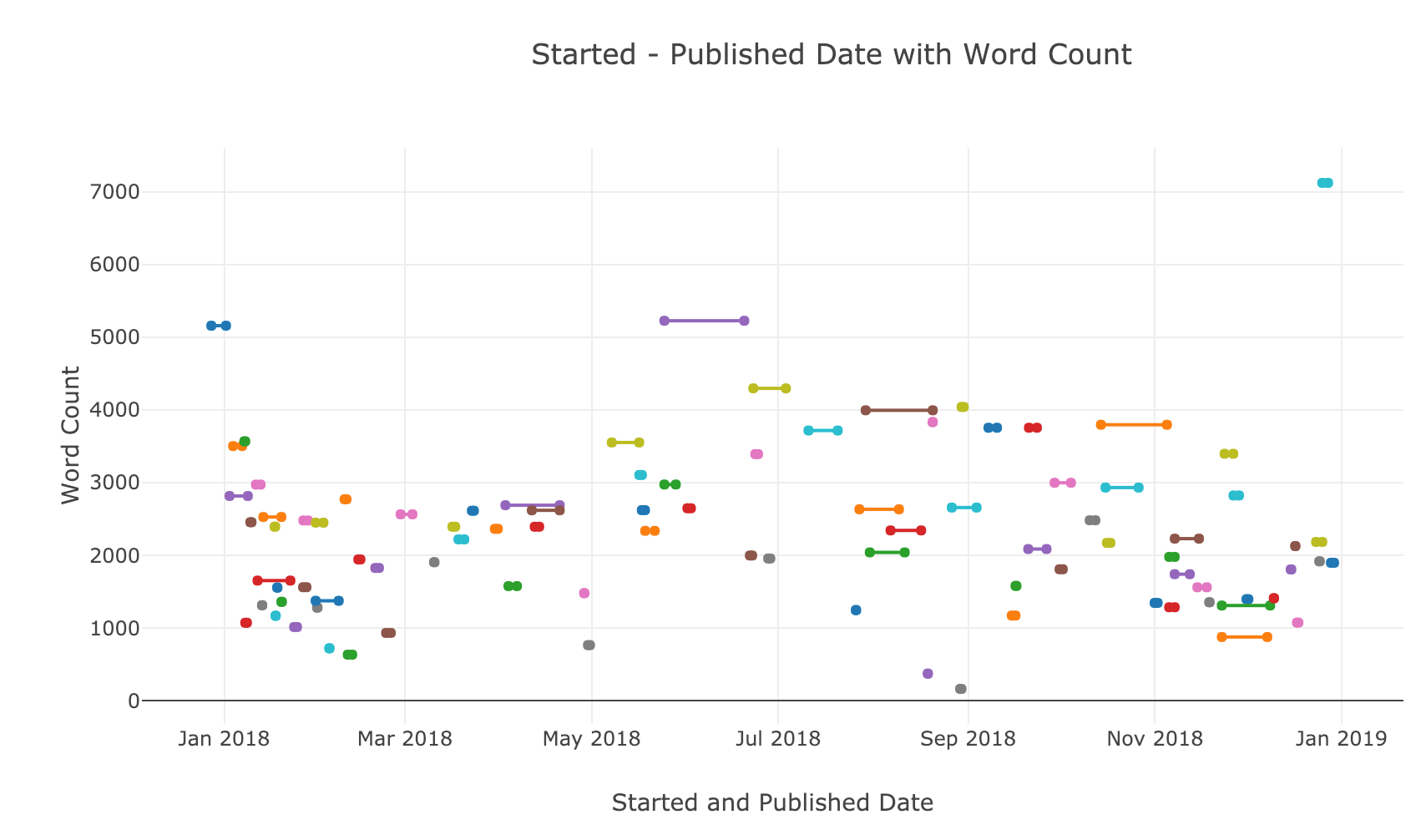

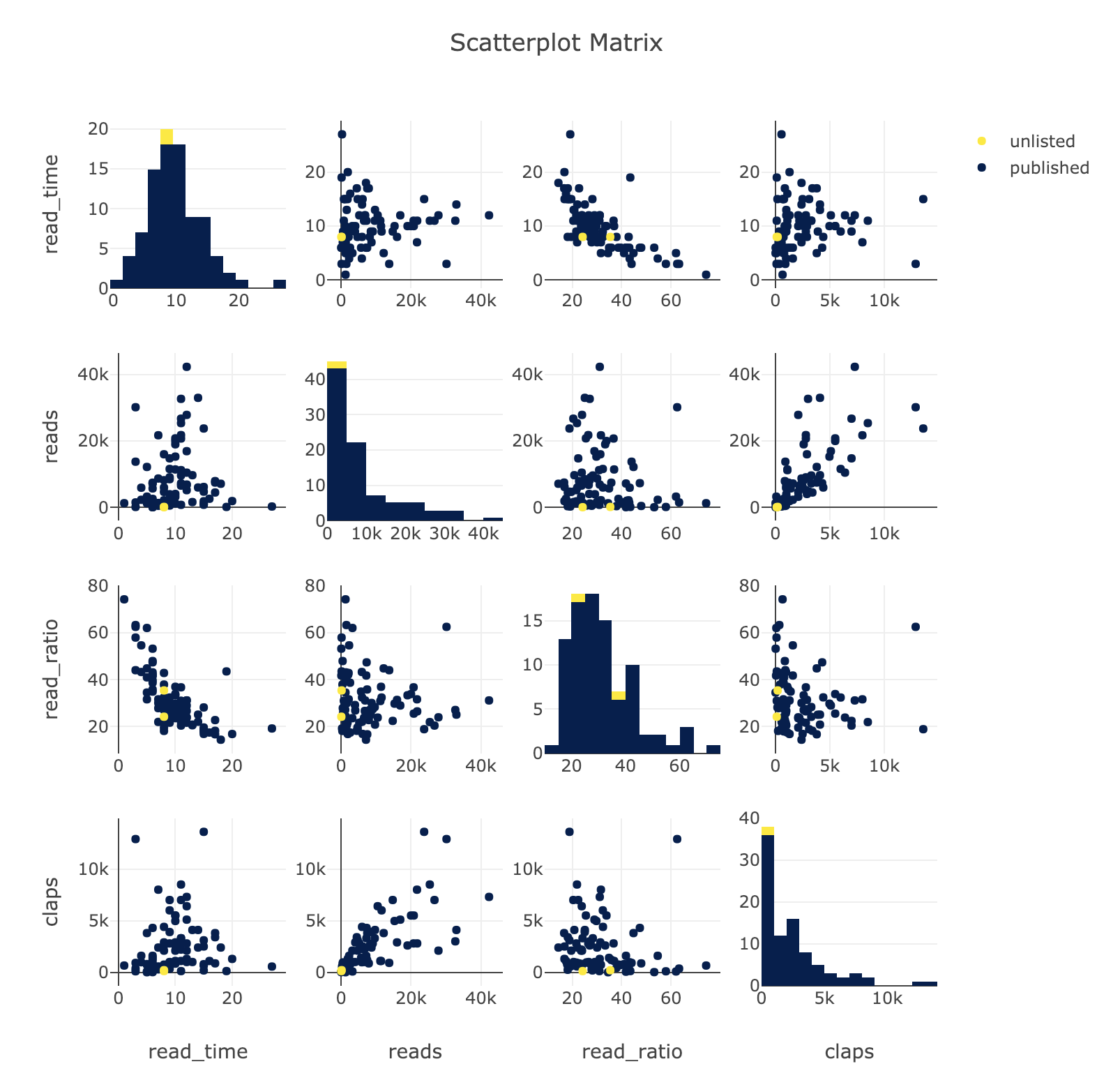

Each of the takeaways is accompanied by a graph of my Medium article stats. You can find the Jupyter Notebook here or get your own stats with this article.

Started and Published Date of All Articles

Started and Published Date of All Articles

1. Everything in data science can be learned without going to school

Mechanical engineering, which I unfortunately studied in college, has to be taught at an institution. It’s just not possible for an individual (at least one with normal resources) to gather the equipment— labs, prototyping machines, wind tunnels, manufacturing shop — needed for a “mech-e” education. Fortunately, data science is not similarly constrained: no topic in the field, no matter how state-of-the-art, is off-limits to anyone in the world with an Internet connection and a willingness to learn.

While I did take a few useful stats classes in college (note: everything in these classes is covered by the free Introduction to Statistical Learning) the data science courses at my college were woefully out-of-date. We were taught tools and techniques that fell out of favor years ago. In several cases, I showed the professor evidence of this only to be told: “well I’m going to teach what I know because it worked for me.” What’s more, these classes were geared toward research which means writing inefficient, messy code that runs once to get results for a paper. Nothing was ever mentioned about writing code for production: things like unit tests, reusable functions, or even code standards.

Instead of relying on college classes, I taught myself (and continue learning) data science/machine learning from books and online courses/articles. I select resources that teach by example and focus on what is actually used in data science in practice today. (By these standards, the best classes are from Udacity and the best book is Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn and TensorFlow by Aurelien Geron.) You don’t have to pay for material: fast.ai has the most cutting-edge course available on deep learning for free; Kaggle gives you opportunities to work on real-world data and learn from thousands of data scientists; and, books like The Python Data Science Handbook don’t cost anything! (Towards Data Science is also useful).

Initially, I wasn’t sure these resources were enough to be successful in data science, but after getting into the field, I found they were more than enough. Few people know what they are talking about when it comes to data science, and if you’ve studied the most recent material available online, you’ll be ahead of most everyone else. In fact, I would argue you are better off learning from online sources/courses, which are constantly updated, than from educational institutions that revise curriculum at most once per year.

All this is not to say that learning data science is simple: you still need willpower and perseverance to study day after day (see more on consistency in 3.). That being said, I find it easier to stay motivated and understand concepts when using material which teaches through hands-on examples. Rather than study the theory first and then look at applications, I use what Jeremy Howard at fast.ai calls the top-down approach: start off with an implementation of the concept that solves a problem, preferably in code. Then, with a framework in place, go back and study the theory as needed.

Finally, I learned to not let data science/machine learning vocab intimidate you. The hardest part of breaking into the field may be learning the terms as it’s difficult to get your bearings when people use words you’ve never heard. Don’t be afraid to ask for clarification on a word you don’t know and, once you do know the meaning of a long word, don’t use it only to sound smart. You’ll sound smarter and be more helpful if you use easy to understand language. (If you need some help, here’s a useful machine learning glossary).

Scatterplot Matrix of Variables

Scatterplot Matrix of Variables

2. Curiosity Drives Data Science

If you look at my articles in 2018, one pattern immediately stands out: there is no pattern! The articles lurch from one topic — random forests in Python — to another — Bayesian regression — to a third — Goodhart’s Law — to a fourth — Recurrent Neural Networks— with no trend. This is a direct outcome of my insatiable curiosity: if I hear something odd in a footnote of an audiobook, read an obscure reference paper, or see a strange tweet, I have to get my hands on some data, write some code, and do some analysis. This can be a blessing or a curse, but fortunately, data science is a good field in which to be curious: Data science rewards curiosity: you must be willing to explore new methods and techniques in order to stay relevant as the field evolves.

Furthermore, being curious about new tools helps you avoid becoming dependent on one library, a lesson I learned the hard way. I spent far too long using matplotlib because of the hours I’d sunk learning it before I switched to plotly. Within 30 minutes, I was as proficient as I’d been with 50 hours of studying matplotlib indicating I should have made the change much sooner! This balance between finding new tools or using the ones you already know has a formalization in the explore-exploit problem. You can spend time exploiting — using what you already know — or exploring — searching for a new method which might be better than the current one.

At the moment, the payoff in data science lies on the explore side: those who are able to seek out and learn new tools are at an advantage because of the rapid pace of change in the field.

Curiosity is also helpful when you’re actually doing data science: exploratory data analysis is driven by the goal of finding interesting patterns in the data. On a somewhat related tangent, Richard Feynman, arguably the smartest man of the 20th century, might be the best proponent for the benefits of a curious mindset. A theoretical physicist, he was as well known for picking up skills (like safe-cracking) or playing practical jokes as he is for his work on quantum mechanics. According to his works, this curiosity was integral to his work as a scientist and made his life more enjoyable.

One of several enjoyable books by Feynman (source).

One of several enjoyable books by Feynman (source).

Feynman was driven not by a desire for glory or wealth, but because he genuinely wanted to figure things out! This is the same attitude I adopt in my data science projects: I’m doing these projects not because they are a required chore, but because I want to find answers to hard problems hidden within data. This curiosity-based attitude also makes my job enjoyable: every time I get to do some data analysis, I approach it as a satisfying task.

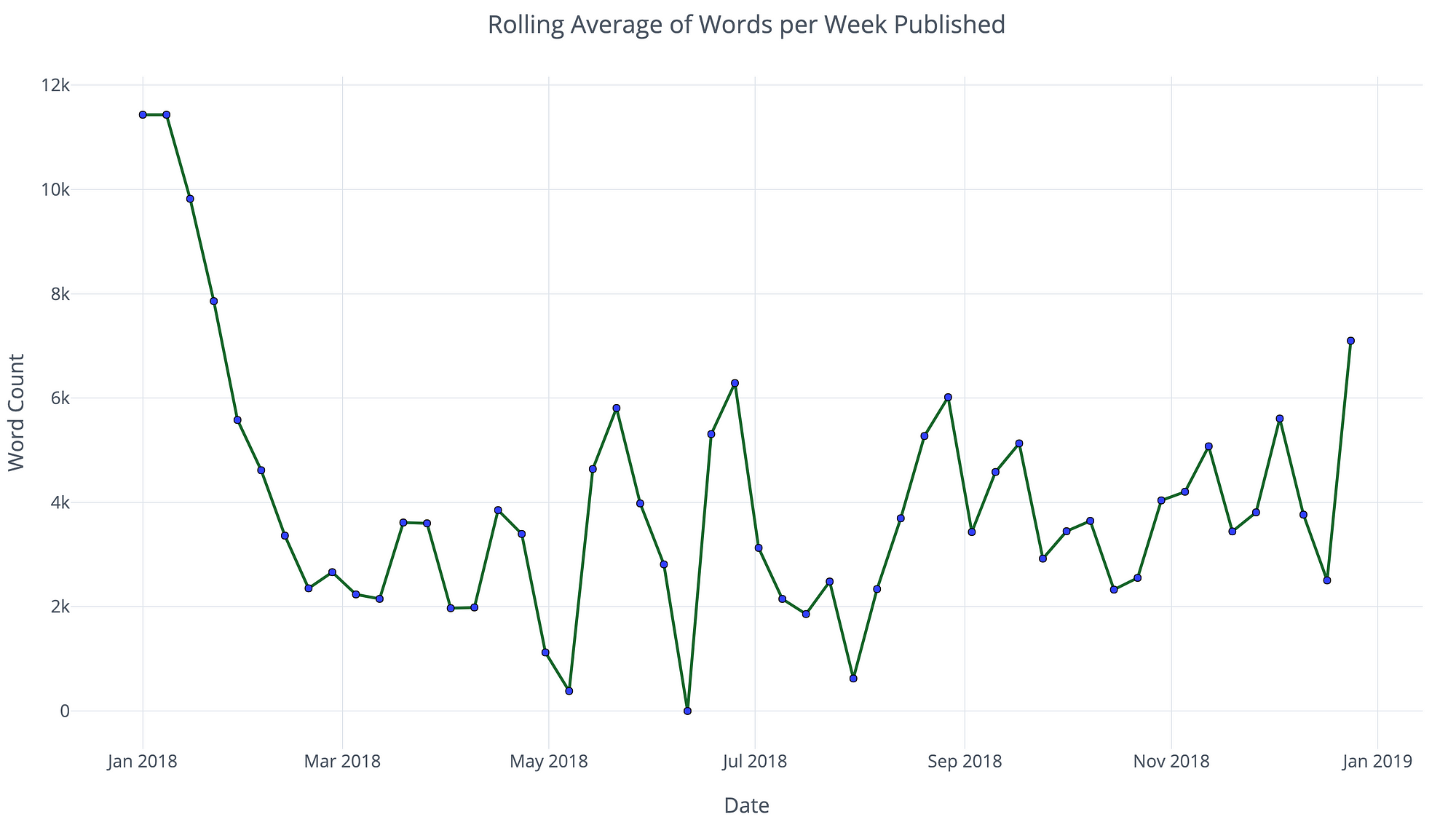

Rolling Average of Words Per Week

Rolling Average of Words Per Week

3. Consistency is the critical factor

The 98 articles I published in 2018 totaled 264,894 words. For every word published, there was at least 1 word that didn’t make it through editing. This works out to about 530,000 words or 1,500 words per day. The only way this was possible studying and working full-time was to make sure I wrote and made progress on my projects every single day. My view is simple: the hardest part of any endeavor is beginning, so once you’ve gotten past that, why stop?

The best analogy for the payoff of writing/working consistently is making regular contributions to a savings account. On a day-to-day basis, you don’t notice much change, but then one day you wake up and your initial investment has tripled (or you’ve written 100 data science articles). It can be difficult to see the benefits if you look only at the progress from yesterday to today, but if you can take a step back and view the long term then you see the value of making a little progress every day.

On a practical basis, you don’t need to write 1500 words per day. I had to make sacrifices to get to that point (I average about 20 hours per week working on articles — unpaid so thanks for the encouragement). Aim for whatever you can, whether that is 300 words, or writing a few lines of code. The key is that you create a frame of mind where writing, or working on side projects, is not an extra hassle, but a part of every day.

Writing and doing data science projects are habits, and like any habits, they become ingrained with enough repetition.

Moreover, writing doesn’t have to be on Medium, or even for a blog post. All writing (even tweets) helps you improve. Start by writing more in your Jupyter Notebooks. The notebook environment is a great tool for data science but is abused (look at this presentation) when people forget its intended purpose, literate programming. Literate programming, as laid out by Donald Knuth, means mixing text, code, and output in the same document, following the natural progress of turning thoughts into code which produces a result.

In addition to thoroughly documenting code with comments, use the text cells (you get an unlimited amount so feel free to make more) to explain your thought process. Documentation is critical to ensure others can understand what you did and is great practice at explaining yourself through writing.

Writing is hard, but it’s a rewarding activity. As a good rule, the things in life that are most difficult — exercise, education, writing — are also those which deliver the greatest long-term benefits. Moreover, all of these endeavors improve with regular practice. Start making regular contributions in your free time now and your future self will thank you for your foresight.

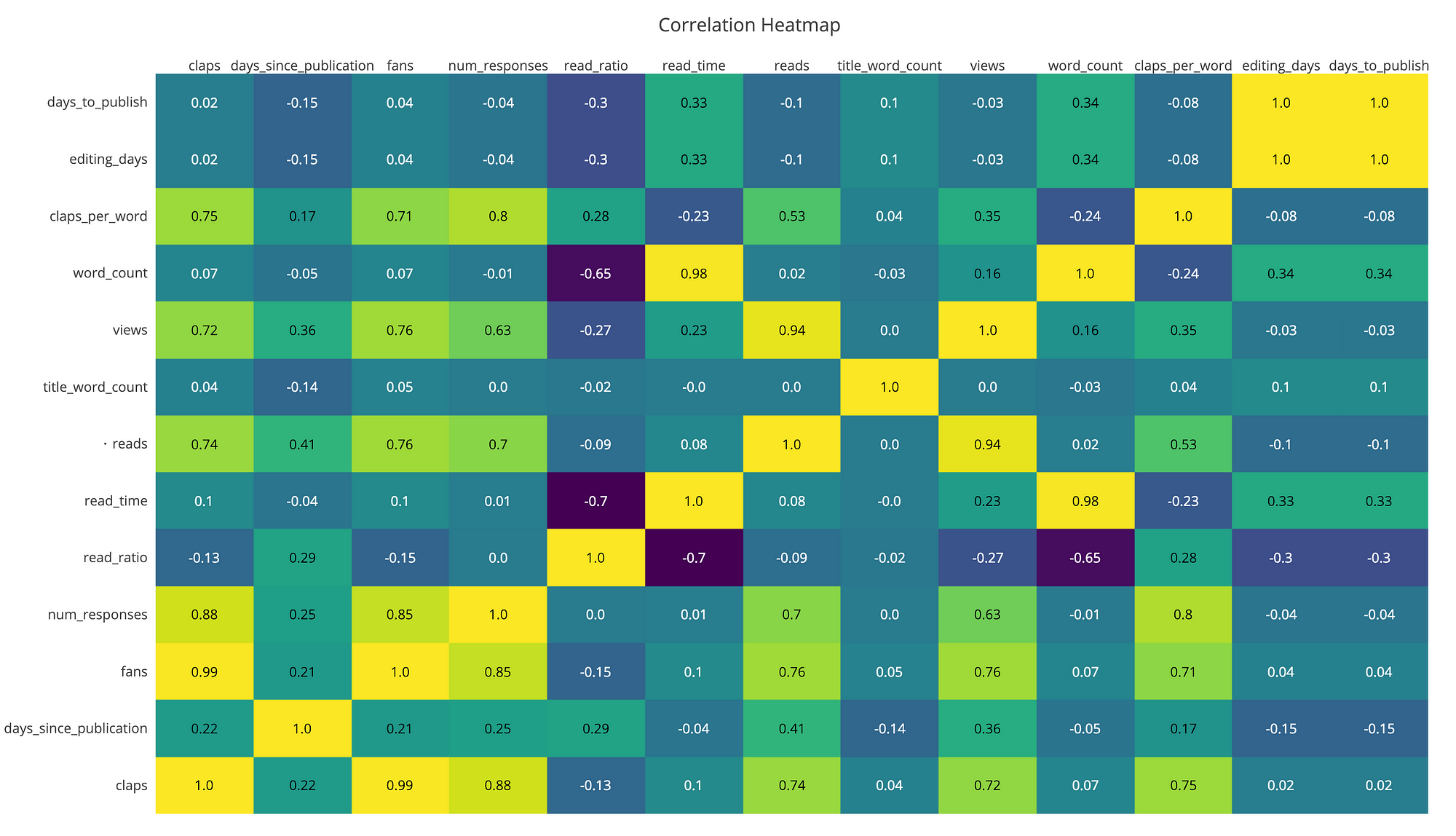

Heatmap of Correlations within Data

Heatmap of Correlations within Data

4. Data Science is Empirical, not Theoretical

What is the optimal number of trees in a random forest? How many rounds of boosting should you run a gradient boosting machine? Which optimizer is the best for your convolutional neural network? What is the most effective dimension reduction technique for highly correlated features?

The answer to all of these questions is the same: you’ll have to experiment and find out for yourself. There are still few hard and fast rules to always follow in data science and even fewer explanations for why things work so well. This means that data science/machine learning is nearly entirely empirical: results are generated not working from theory but through experimentation.

This lack of accepted solutions can be frustrating. How am I supposed to set the hyperparameters of my random forest? At the same time, it can also be enabling: there are no “right” answers which is great for tinkerers who like to experiment. At the very least, you need to be prepared to ask a question only to be told you’ll just have to write the code and find out for yourself.

(As a note, I think it’s worth separating best practices — things like code reviews and following pep8 for code style — from the best methods for tasks like regression or dimensionality reduction. There are best practices to follow but the methods are still being sorted out.)

A good approach to data science is to view yourself as a perpetual beginner. Knowing a lot is better than not knowing much, but it can also be constraining. You can’t see past the methods you’ve always used to the better option that was just invented (remember explore/exploit?). Accept that you’ll never reach “the end of data science knowledge” and be willing to try out new techniques even if no one else is. Also, when someone tells you there is only one right way to do something in machine learning, be very skeptical. Data science is still a level field where the experts aren’t necessarily the ones best equipped to solve a particular problem; if you think someone (especially me) is doing some project suboptimally, point it out!

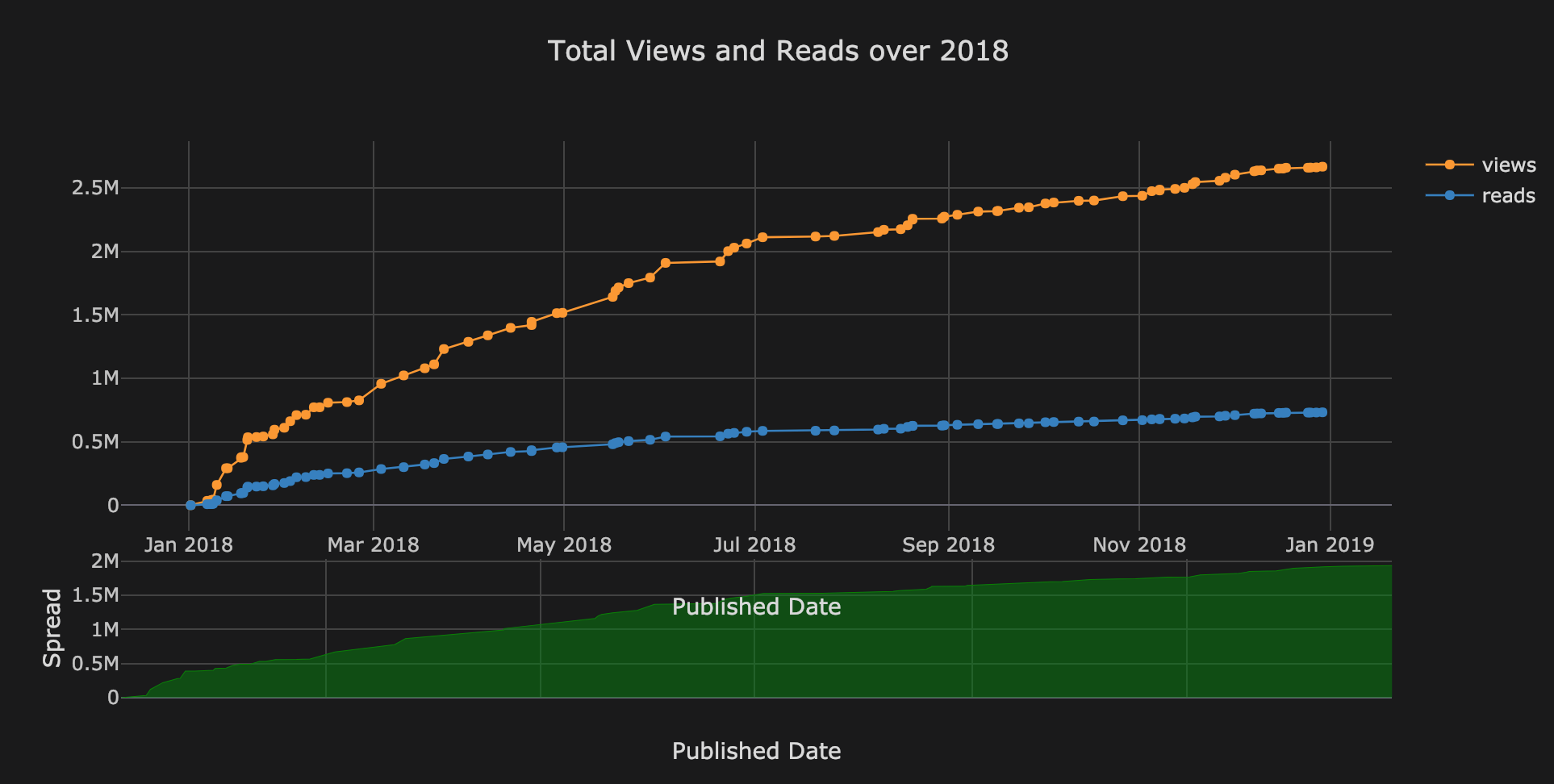

Total Views and Reads in 2018

Total Views and Reads in 2018

5. Writing Delivers Real Benefits to Writers and Readers

Mutualism is a form of symbiosis in which both organisms benefit from a relationship. Our gut bacteria is a perfect example: it gets to feed off our digestive products while we enjoy health benefits. To tie this back to data science, writing is also a symbiotic relationship because both the writer and the readers come out ahead. When I finish an article about data science, I never know if the greater benefit accrues to me or those who read the post.

Writing is literally thinking. It forces you to sort out your thoughts, and explaining concepts to someone else — especially with simple language — requires deep understanding. Writing drives me not only to study more so I know what I’m writing about, but it also lets me form simple explanations that I can use at my job to explain concepts to a wide (non-technical) audience.

The other way I’ve benefitted from writing (besides earning two jobs) is being part of a larger community. Writing and seeing other people benefit from my articles gives me a greater sense of fulfillment than anything I do on a day-to-day basis. Not to get too sentimental, but being a “writer” is as much a part of my self-definition as anything now and it gives me the motivation to get up early on the weekends and write to contribute to the community.

On the other side of the relationship, I certainly hope people are better off from this writing. In my transition into data science, I received tons of help from the community, and writing is my small way of paying it forward. Further, my articles are free to read because I believe everyone in a field benefits when knowledge is allowed to spread without barriers.

Beyond free knowledge, the field of data science will be better off when more diverse people are attracted to it. A field benefits as it diversifies because of the new ways of approaching and working through problems different individuals bring (this doesn’t just sound good, it’s been proven). Data science is a great field, and I don’t want to see it crippled by homogeneity. If my articles can help expand data science to a wider audience then the entire community will be richer.

Often I see the idea that if someone is successful in their field — for example they have earned a stable job — their work is done. In contrast, I think once you make it into a field you have an obligation to turn around and help up the next person. Better yet, build an elevator to get as many people into the field as possible.

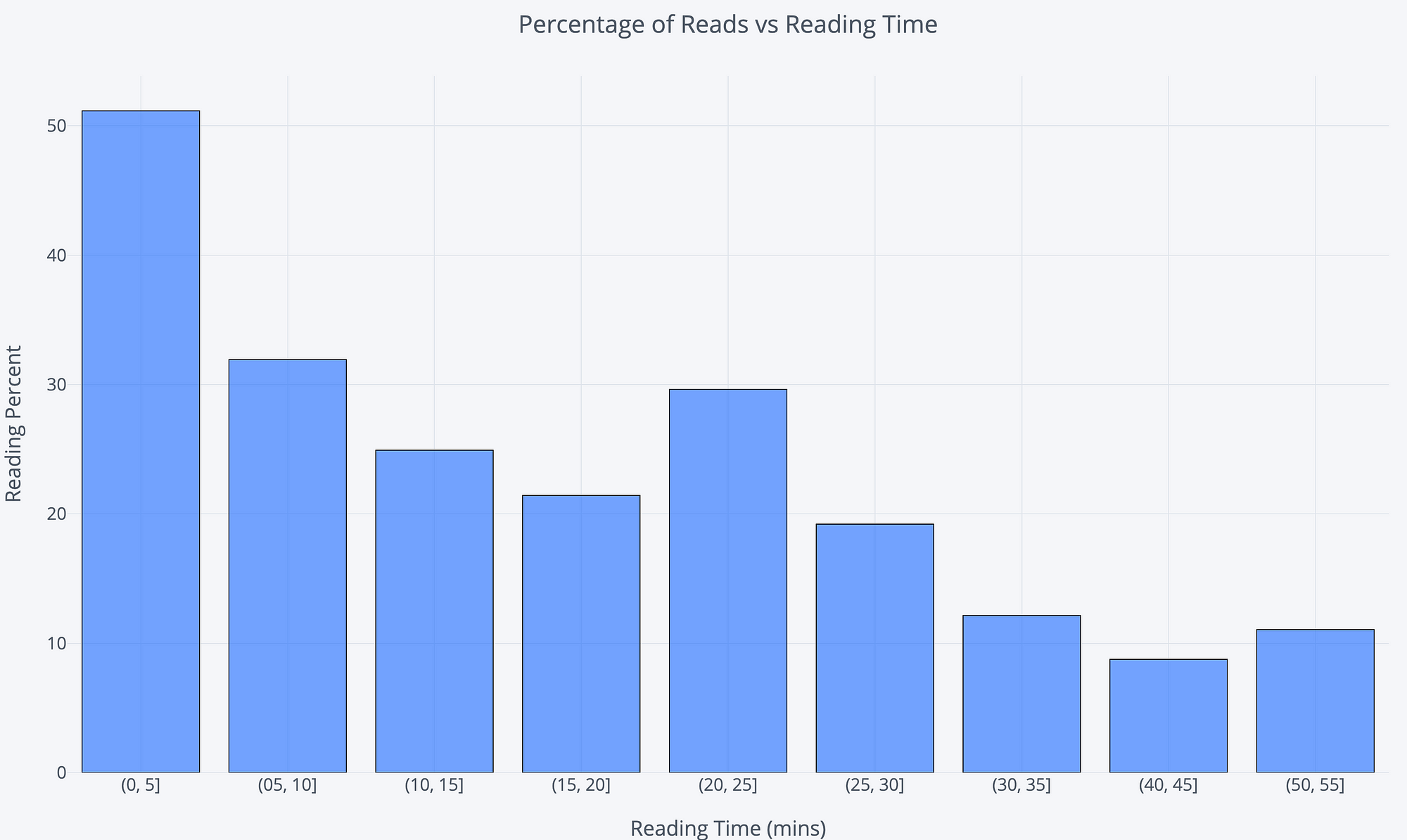

Percentage of reads (reads / views) by Reading Time Binned

Percentage of reads (reads / views) by Reading Time Binned

Conclusions

To wrap, these are the takeaways from “The Year of Data Science Writing”

- Data science does not require formal education

- Curiosity powers data science

- Data science and writing are habits which get better with practice

- Experimentation in data science is required

- Writing will benefit you and the community

While there are plenty of other things I could be doing with my time, it’s hard to imagine anything else that would deliver as many benefits both to myself and to others as the act of writing about data science. Although I’ve branched out into data journalism this year (to become less wrong about the world with data), I’ll continue writing about standard data science: projects, tools, and techniques you might find useful.

As a final point, consider this: writing is one of a few activities in our lives over which we have complete control. Start from a blank page, over days or weeks put your thoughts onto the page, and, eventually, you’ll have a work created entirely from your own mind that can travel around the world to millions of people in seconds potentially improve your life and theirs. That is the definition of magic — now go out and practice data science writing.

As always I welcome constructive criticism and feedback. I can be reached on Twitter @koehrsen_will.