Published on December 16, 2017

When I’m wrong, call me out!

Here’s a radical idea: every time you refrain from correcting someone out of politeness, you are doing them a disservice by robbing them of a valuable opportunity for self-improvement.

Lately, I have noticed a disconcerting trend: people in daily life are more reluctant to point out and correct other’s mistakes. This has been most pronounced than in the classroom where it seems to be impossible for a student to actually give a wrong answer. Instead, they are “on the right track” or “have the basic concept” no matter how far away from the correct response they actually are. Now, I understand professors may not want to discourage a student by flat out telling them they are wrong, but despite recent political developments in the US, we are not living in a post-truth world. There are still right and wrong answers, optimal ways to solve a problem, and opinions that belong in “the dustbin of history.” The aversion to correcting false statements extends beyond the classroom. In my time with NASA, I sat in on many meetings where a manager said something all the engineers knew was technically wrong, but no one would ever think to speak up and point this out. Afterwards, we talked about how the manager had no clue how things actually got done, but instead of explaining that to him, we let him continue in his false beliefs. As a final example, consider a typical scenario in the early rounds of the popular singing contest American Idol: a young contestant, full of enthusiasm and confidence walks onto the stage and belts out an absolutely unbearable rendition of a pop song. How on Earth did they come to believe they had any singing talent? Because no one had ever been told them how bad they really were. For years, they had been surrounded by family and friends who politely told them they were a great performer, a delusion that finally was shattered in front of a national audience. All it would have taken was a single honest person to tell the contestant that maybe they should pursue a different path to save them hours of wasted effort and the embarrassment of a failed audition.

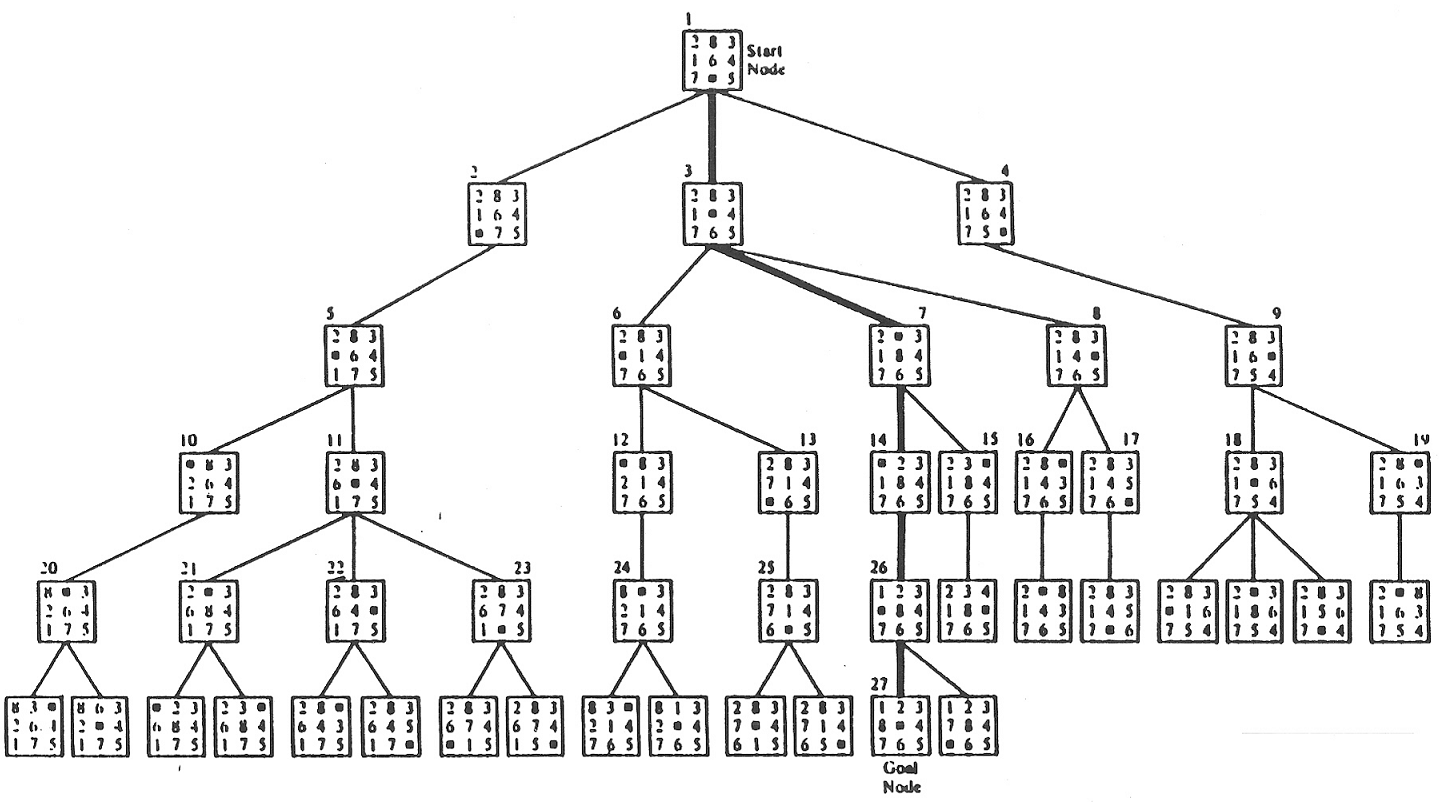

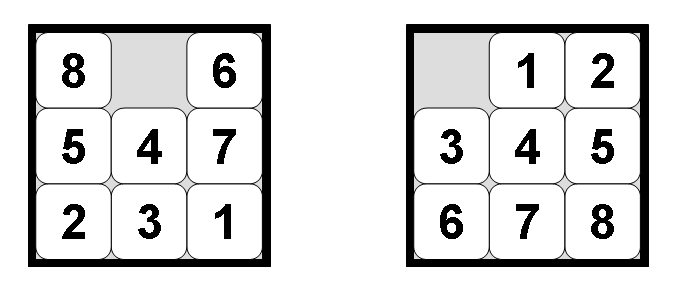

Eight Puzzle Search Tree

Eight Puzzle Search Tree Figure 1: Eight Puzzle in Unsolved and Solved State

Figure 1: Eight Puzzle in Unsolved and Solved State